John Richardson = Margaret Stead

| ↳ other children

Isaac Richardson = Deborah Sutton

| ↳ other children

Edward Richardson = Jane Wigham

| ↳ other children

Elizabeth Richardson = Robert Spence Watson

| ↳ other children

Mary Spence Watson = Francis Edward Pollard

Elizabeth Richardson was born on the 12th September 1838, at 6 Summerhill Grove, Westgate, Newcastle. Her childhood was very happy. One of a large family, with parents who fostered the intellectual interests of their children, she had greater scope and a wider horizon than many girls of the period, and she had opportunities for the physical activity which laid the foundation for her splendid health and strength.1

At the time of the 1841 census she was living with her family and four female servants in Summerhill Grove, Westgate. She was sent to school at the age of three, attending for a year or so at a school in Westgate Road, just below the entrance to Summerhill Grove, kept by two Friends, Mary Jane and Phoebe Goundry. She was next, at about the age of seven, at school at Mrs Gethings's, in Westmoreland Road, and afterwards (or perhaps before) in Elswick Row. While there she repeated all 54 verses of 1 Corinthians 15, and received 4d as a reward. One of her schoolmates later recalled her great enthusiasm about a voyage to Edinburgh in the early days of steamships, and her tears on reading of the cruel treatment of Prince Arthur in the reign of King John.2

The children of her parents' household were not allowed sugar because it was slave-grown. The one deliberate lie (if it merits the term) that troubled her conscience was, that as a little girl she asked her father for her Saturday penny earlier than usual, and when he asked her "What for?" she replied (knowing that she intended to buy sweets) "Nothing particular."3

Like all her family, she was a horsewoman, and she was given a pony, on condition that she tended it entirely herself, and on it she used to gallop barebacked. She was only once thrown, when cantering up Benwell Lane. Later the family had a phaeton, and she grew familiar with harnessing and driving. Riding with her husband was a favourite form of exercise and relaxation in the busy life of later years.4

In the summer of 1847 she holidayed with the family in lodgings at Whitburn. Around the late forties the Richardsons were visited by George Catlin's Indians; Elizabeth fell in love with a little Indian boy, about her own age, who was beautiful in her eyes.5

In 1848 she was taken to see her grandmother [O17] Deborah Richardson, when she was dying. She was rather a favourite of her grandmother's—she remembered once when she had thought her very good on a fourth day meeting, she took her to Bell the confectioner's afterwards, and bought her twelve sponge cakes and 1lb of barley sugar. Jane Richardson locked them up to be gradually consumed.6

Around 1850 she was taught at home for a year by her elder sister Anna Deborah Richardson. She found her sister to be a teacher with intellectual ability, understanding, and sympathy, one with whom it was indeed a pleasure to learn.7

![]() The

1851 census found her living with her family, two housemaids, and a cook, at 6 Summerhill Grove, Westgate, Newcastle.

That year she was sent to a school at Lewes, in Sussex—run by two Friends, the sisters Dymond—where Anna had been before her. Though this seems a long way to go, one of

the teachers—Sarah Rickman—was a friend of her mother's, and there seems not to

have been a suitable school nearby. She was taken as far as London by Anna, staying

in lodgings there a few days; she saw the sights of the city and the Great Exhibition.

She didn't come home at all during her first year at Lewes, owing to the length of the journey;

school terms then were two half-years, so she spent Christmas at Staines, with some

Friends named Ashby. At the end of her first year she went to Nab Cottage with her

family, in June, before the removal to Beech Grove. School life would be considered

Spartan in these days, bread and butter only for breakfast and tea, with a spoonful

of jam once a week. But there was plenty of outdoor exercise in the fine air, more

freedom than was allowed in most schools, and excellent teaching which inspired

and stimulated the scholars. School began at 7 a.m., with an hour's work before

breakfast. Among the subjects taught were English, German and Science. With another

girl, Martha Gibbins (later Hack), at one point Elizabeth Richardson manufactured

a rude electrical machine, with stool and Leyden jar all complete for the giving

of shocks, to demonstrate to the girls. Elizabeth used to speak with great affection

of the Dymonds, and looked back to her school days as very happy ones. She left

Lewes in her sixteenth year.8

The

1851 census found her living with her family, two housemaids, and a cook, at 6 Summerhill Grove, Westgate, Newcastle.

That year she was sent to a school at Lewes, in Sussex—run by two Friends, the sisters Dymond—where Anna had been before her. Though this seems a long way to go, one of

the teachers—Sarah Rickman—was a friend of her mother's, and there seems not to

have been a suitable school nearby. She was taken as far as London by Anna, staying

in lodgings there a few days; she saw the sights of the city and the Great Exhibition.

She didn't come home at all during her first year at Lewes, owing to the length of the journey;

school terms then were two half-years, so she spent Christmas at Staines, with some

Friends named Ashby. At the end of her first year she went to Nab Cottage with her

family, in June, before the removal to Beech Grove. School life would be considered

Spartan in these days, bread and butter only for breakfast and tea, with a spoonful

of jam once a week. But there was plenty of outdoor exercise in the fine air, more

freedom than was allowed in most schools, and excellent teaching which inspired

and stimulated the scholars. School began at 7 a.m., with an hour's work before

breakfast. Among the subjects taught were English, German and Science. With another

girl, Martha Gibbins (later Hack), at one point Elizabeth Richardson manufactured

a rude electrical machine, with stool and Leyden jar all complete for the giving

of shocks, to demonstrate to the girls. Elizabeth used to speak with great affection

of the Dymonds, and looked back to her school days as very happy ones. She left

Lewes in her sixteenth year.8

While at Lewes the girls had Uncle Tom's Cabin read to them. Elizabeth later met Harriet Beecher Stowe and her family, and remembered hearing the song 'Swanee River' first sung by the Stowe daughters.9

spencewatson_1855.jpg)

Elizabeth Richardson, 1855

She felt deeply the deaths of her brother Isaac at the age of five, and especially of her sister Margaret, at four (1846 and 1855 respectively)—"I felt as if I could not bear the parting, for I loved her passionately."10

In 1856 she visited Rotterdam.10A

On returning home she studied at the School of Art under William Bell Scott, and while there she became engaged to [M2] Robert Spence Watson.11

The 1861 census found her living with her family and four general servants at 1 South Ashfield Villa, Elswick Lane, Elswick, Newcastle. On the 7th April 1861 she was appointed as one of two women from Newcastle Women's Preparative Meeting to attend Monthly Meeting in Shields the following fourth day. In November 1861 and September 1862 her father's private ledger recorded gifts of £5.0.0 cash to her, though no reason is given. In 1862 she saw the sights of Paris, with Emily and John Wigham Richardson.12

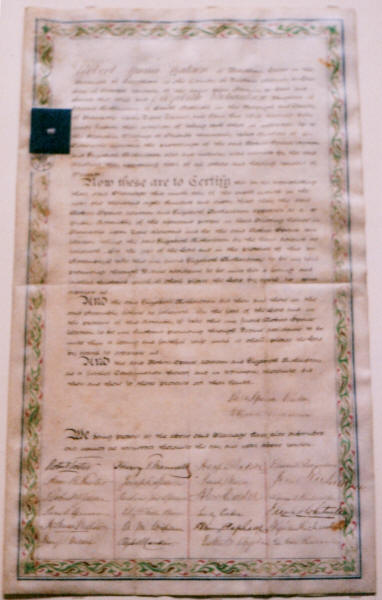

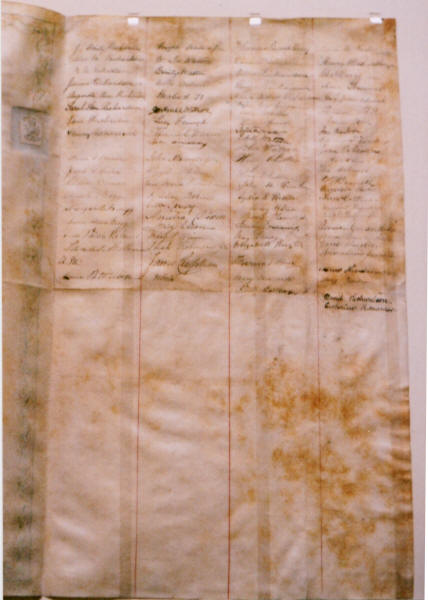

In April 1863 Newcastle Monthly Meeting appointed Henry Tennant and Robert Foster to enquire into the clearness for marriage of Robert Spence Watson and herself, with Robert Foster giving notice to Newcastle Preparative Meeting. The following month they were liberated to marry, with Robert Spence and Robert Foster given the task of ensuring conduct according to good order. On the 22nd May Edward Richardson paid out £10.0.0 "for Lizzie". Elizabeth and Robert were married at Newcastle meeting house on the 9th June 1863.13 The Newcastle Journal reported as follows:

MARRIAGE FESTIVITIES.—Yesterday morning, the marriage ceremony was celebrated between R. Spence Watson, Esq., solicitor, and Miss Elizabeth Richardson, daughter of Edward Richardson, Esq., South Ashfield, Elswick Lane, at the Friends' Meeting House, Pilgrim Street. There was a large muster of the relatives and friends of the happy couple, who arrived in ten carriages, and entered their place of worship under a canopy placed across the pavement in Pilgrim Street. The interesting ceremony was performed in the usual manner adopted by the Society of Friends. After it was over, the bride and bridegroom received the hearty congratulations of all present. A large number of the younger branches, who had been present, enjoyed the remainder of the day in pic-nic parties in the neighbourhood of the town. A most gratifying feature of the day's proceedings was the treat given to the children of the Ragged Schools. Mr. Watson is one of the secretaries to the gentlemen's committee of the Ragged Schools, and his bride one of the secretaries to the lady's committee. The children of the schools, after having had breakfast in order to commemorate the auspicious event, were drawn up in the court-yard shortly after eight o'clock, the girls under the care of the schoolmistress, on one side, and the boys, under the care of Mr. Morgan, on the other side of the yard, the whole acting under the direction of Mr. G.A. Brumell. They then sung several songs, after which a number of cannon, which had been mounted in the yard, were fired; and as each cannon was discharged, the children cheered loudly. They again sang a number of songs, and gave a hearty cheer for the future happiness of the two secretaries, whose marriage they were met to celebrate. The children dispersed to amuse themselves, and at the time appointed for the wedding, nine o'clock, a rocket was fired, and the cheering again commenced. The children then went to their school duties. At noon, the same rejoicings were repeated, with the addition of a small present for everyone who attended the schools, which had been kindly provided by the bride and bridegroom. From different parts of the building flags were hung out, which, together with the cheering, made those in the neighbourhood aware that something out of the ordinary was going forward. The countenances of the children betokened happiness and contentment, and the wish of each child was, that every joy and comfort might be showered down upon the happy pair, who had done so much for their benefit. At Messrs. Richardson's tannery, Newgate Street, a number of flags were displayed.

spencewatson_1863.jpg)

Robert and Elizabeth Spence Watson, 1863

Quaker marriage certificate for Robert Spence Watson and Elizabeth Richardson (with apologies for the poor focus)

And the Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury reported:

WEDDING AT THE FRIENDS' MEETING HOUSE.—The marriage of Mr. Robert Spence Watson, son of Mr. Joseph Watson, solicitor of this town and Bensham Grove, Gateshead, with Miss Elizabeth, third daughter of Edward Richardson, Esq., South Ashfield, Newcastle, was solemnised at the Friends' Meeting House on Tuesday. Long before the time appointed for the ceremony taking place, the vicinity of the chapel was crowded by persons anxious to see the bridal party, which, about half-past nine, arrived in seven carriages—four of them being distinguished by having outriders, and the whole of the horses, postilions, &c., wearing wedding favours. The bridal party comprised Mr. and Mrs. Richardson, Mr. and Mrs. Watson, the Bride and Bridegroom, Mr. H.T. Mennell and Miss Jane Emily Richardson, Mr. Thomas Whitwell and Miss Emily Watson, Mr. Joseph Watson jun., and Miss Lucy Fenwick, Mr. John W. Richardson and Miss Alice Richardson, Mr. William Joshua Watson and Miss Ellen Ann Richardson, Mr. George W. Richardson and Miss Helen Watson, and Master Herbert Watson and Miss Gertrude Watson. The bride and bridesmaids were all gracefully dressed in white. The meeting house was filled by a large audience, chiefly friends of the parties, many of whom had come from a distance. Upon the bridal party proceeding to the table the usual forms were gone through, after which Mr. Charles Brown, of North Shields, delivered an appropriate and impressive discourse from the words "Commit thy ways to the Lord." The happy couple took their departure by the 1.30 p.m. train for the south, en route to Switzerland, where they intend to spend the honeymoon. The children of the Ragged Schools, of which the happy couple were secretaries, had rejoicings on the occasion, and at Messrs. Richardson's establishment in Newgate-street, various flags were displayed in honour of the event.13A

On their wedding night, at the London Bridge Terminus Hotel, the hotel was evacuated for a time, on account of a fire. On their six week honeymoon in Switzerland and North Italy Elizabeth made, with Robert, the first ascent of the Balfrin. They visited Switzerland and Italy again in 1865 (with Emmie and Allie Richardson) and 1867. In 1867 she made the first or second ascent by a lady of the Ortlerspitze, as well as ascending the Königsspitze and the Ortlerspitze. She travelled widely with her husband in their concern for freedom, visiting Switzerland, Norway, Corsica, the Pyrenees, Dauphiny, Madeira, and Tenerife; they made their first journey to Norway in 1868.13

The couple had six children: Mabel Spence (1864–1907, born at Moss Croft, Gateshead), Ruth Spence (1866–1914, b. Moss Croft), Evelyn Spence (1871–1959), [M1] Mary Spence (1875–1962), Bertha Spence (1877–1954), and Arnold Spence (1879–1897).14

On 26th November 1863 Elizabeth launched the East India clipper Delhi, from her brother's shipyard.14AA

After Ruth's birth in 1866 Elizabeth was very ill, and took a month to recover.14A

Once, with Robert at Tynemouth, she saw three separate shipwrecks in one afternoon, in a stormy sea.15

Her father-in-law, Joseph Watson, used to say "A sweeter woman ne'er drew breath than my son's wife, Elizabeth" (from Jean Ingelow's 'High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire').16

Around the late 1860s she translated from German some large treatises on philosophical subjects which her (future) brother-in-law Dr Theo Merz was then writing.17

On the 6th of April 1868 Elizabeth recorded in a private note:

In the last few weeks, I have not been very well, having been much troubled with cough & rheumatism. Often I have been much discouraged, not about my physical state, but because I seem to make so little real progress in anything that is good, & because I find the "being faithful in little things" so very hard. Ill temper so often given way to & excused to myself under the plea of being tired, or not feeling well—indolence, & neglect of what I choose to call little duties—how often all these sins beset me. And yet if I cannot be faithful in the little how can I be faithful in much? & how unless I myself strive more earnestly can I expect to teach the children to be gentle & patient? But what I want is not to reason or talk about these things—I believe I am conscious of many of my faults, & I doubt if a somewhat morbid self-analysis is likely to do good.17A

In the summer of 1868, with Robert, she made her first trip to Norway. In the autumn of 1869 they visited Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, &c. In December of that year her sister Anna Deborah commented on their activities:

Lizzie is very well . . . I sometimes think he [RSW] works his wife too hard, for she has not so good a constitution as he, especially in their ridiculous Alpine and Norwegian pranks; where, for example, they will walk 40 miles over ice one day, and drive 70, in a rattling 'carriole,' the next; but, so far, the paralysis which I expect for them both some day, is happily warded off.

In the summer of 1870 they visited Austria. They were abroad at the start of the war between France and Germany, and had considerable difficulty in getting back.18

The 1871 census found her living with her family and two domestic servants in Elysium Lane, Gateshead. In December of that year Elizabeth recorded, of her life at that time, "Of course . . . my time is almost entirely taken up with household work, & I have scarcely any leisure for reading."19

In 1871, 1872 and 1873 the family took summer holidays mountaineering in Switzerland. In January 1872 they took a winter break in Tenerife. Around 1873 it is recorded that Ann Richardson Foster offered a silk dress to Elizabeth if she or her husband could peel an apple into as many yards (not less than ten) as would make one, and keep the peel unbroken. The task was performed, and the peeling—ten yards and two feet long—was presented to the donor with a poem by Robert to accompany it. The summer holiday of 1874 was spent in Belgium and France.20

In April 1874 she played Portia in the family's production of Ye Marchand of Venyse at Mosscroft, and later that month Decius Brutus, in Julius Caesar; in May she played Regan in King Lear, and in November the Duke of Norfolk and John of Gaunt in Richard II. Some time after mid-April that year she inherited a seventh part of her mother's residual estate. In August, with Robert and his sister Gertrude, she represented Gateshead at a conference of the Friends' First Day School Association, in Darlington. In early 1875 she was still living at Moss Croft, Gateshead, though Robert had inherited Bensham Grove by the death of his father in December. In the late autumn of that year Elizabeth spent a couple of weeks with the children, staying with her sister Emily White and family at West Knoll, Bournemouth, while Bensham Grove was made ready for them to take up occupation.21

In 1876 Elizabeth noted:

I do not know that I have ever remarked upon the delightful rides Robert & I have had together—at one time or another in the course of our married life. Both in the old Ashfield days but more especially since Alice's wedding—for Dr Merz made her a present of a beautiful horse called Rose, a splendid creature wh we have been fortunate enough to ride as well as its mistress. In the long spring evenings, & especially in the particularly beautiful ones of last spring, when the woods were carpeted with hyacinths, & everything looked lovely, we had some never to be forgotten rides—finding out new paths & new beauties every day. Now we have a nice little horse of our own called Jessie, wh Mabel rides admirably, & wh is also large enough for either Robert or me.21A

In 1876 and 1877 she holidayed with her family in Aardal and Faleide, Norway. In the latter year she made the first ascent by a woman of the Store Cecilienkrona. In October that year she noted:

What with home duties & cares—sewing (no light matter when 5 girls have to be provided for) much correspondence, & Ragged School & Training Home work outside not to speak of social duties—I find my time completely taken up—& have little leisure for reading, except just the morning's newspaper.22

At the beginning of June 1878 Elizabeth and Robert were at Pooley Bridge. In the autumn of that year they spent 6 weeks touring northern Italy. The following year they holidayed on the Isle of Wight.22A

In February 1880 she attended a meeting to petition for women being allowed to take exams at Cambridge.23

In 1880 Robert, Elizabeth and Mabel Spence Watson visited Sweden, where Robert had business. In London, on their way out, they had seen Henry Irving and Ellen Terry in The Merchant of Venice.24

At the time of the 1881 census she was living with her family and four general servants at Bensham Grove, Bensham Road, Gateshead.25

The family spent six weeks at Faleide again, in 1881, taking two maids out with them. On their return, Elizabeth noted, "Newcastle & Gateshead looked too dirty to live in, but Home is Home . . .". Soon after her return she had a fall in which she injured her knee sufficiently that she was "quite crippled" for some weeks. Similar periods were spent at Faleide in 1882 and 1884, the summer of the intervening year once again being spent in Switzerland and North Italy. In 1885 the family again returned to Norway for the summer, this time to Ørstenvik. 26

From before her marriage she remained for over forty years Secretary to the Committee of the Ragged and Industrial School for Girls, and with her husband was a prime mover in the founding of, and secretary to, the High School for Girls in Gateshead—the first girls' day school in the north east.27

She was an ardent believer in Home Rule for Ireland, and campaigned with her husband during the period 1885/1890. She is also known to have corresponded at length with Josephine Butler, the feminist and social reformer.28

In the Autumn of 1886 she and Robert took a trip in the Tyrol, returning via Basle.29

The Newcastle Women's Liberal Association was founded at Bensham in 1886, and Elizabeth remained its President for 25 years. At the branch in 1887 she read a paper on 'A Summary of the Reforms Passed Since 1832', which was published. A large number of the WLAs in Northumberland and Durham were inaugurated with speeches by her. Where the Newcastle and Gateshead WLA appears to be different from the others is the high profile given to the question of peace, certainly not part of the official Liberal Party policy. Elizabeth raised the peace question at most WLA meetings.30

She was a member of the Gateshead Nurses' Association, the Girls' Friendly Society, the Women's International League, the Tyneside Association, the Band of Hope, the British Women's Temperance Association, and the Women's Suffrage Society—she was President of several and took an active interest in all. She was a member of the Tyneside Peace and Arbitration League, and of the Newcastle and Gateshead Vigilance Association. In late 1889 she wrote to Sergei Stepniak, wondering (perhaps rather naively) if a personal letter from Queen Victoria might help the Russian cause; from 1890 she was a member of the general committee of the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom, working actively for the society, sending out circulars and sending updates to Stepniak on the progress of subscriptions. In 1890 was also a member of the council of the Women's Franchise League, and in 1900 was one of the founders of the Newcastle and District Women's Suffrage Society, becoming an active member of its executive committee.31

In

February 1887 she visited Lewes with Robert. In the summer of that year the family

spent six weeks in Norway, staying for part of the time at least inside the Arctic

Circle, at Ørnaes; they returned to the same place in 1888, in which year Elizabeth

and Robert also made a silver wedding trip to Spain. Elizabeth donated 10s. to the

British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1888—enough for annual subscription,

but she appears not to have renewed it. In November 1888 she founded the Newcastle

and Gateshead Ladies Peace Association. The following month she visited London with

Robert; and in January 1889 she stayed at Naworth Castle, Brampton, Cumberland.

During April and May that year, with Robert, she toured Rome, Naples, Sicily, Venice,

and then Dresden and Berlin (where they saw Bismarck and the Kaiser). In November

1889 she addressed the 2nd annual meeting of the Newcastle & Gateshead

Peace Association, on the Franco-Prussian War. The summer of 1890 saw the family

in Osen, Norway, for seven weeks. The 1891 census finds her with her family at Bensham

Grove, in a household including Robert's nephew, a cook, and two other domestic

servants. She spent five weeks with Robert in a tour of Spain, as well as a few

days in Tangier, in the autumn of 1891. In the early part of 1892 Elizabeth spent

four months with her daughter Mabel, who had been ordered south for her health,

in the Canaries. Later that year she spent six to eight weeks with Robert, at a

house called Bryn Cothi, in Caermarthenshire.32

In

February 1887 she visited Lewes with Robert. In the summer of that year the family

spent six weeks in Norway, staying for part of the time at least inside the Arctic

Circle, at Ørnaes; they returned to the same place in 1888, in which year Elizabeth

and Robert also made a silver wedding trip to Spain. Elizabeth donated 10s. to the

British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1888—enough for annual subscription,

but she appears not to have renewed it. In November 1888 she founded the Newcastle

and Gateshead Ladies Peace Association. The following month she visited London with

Robert; and in January 1889 she stayed at Naworth Castle, Brampton, Cumberland.

During April and May that year, with Robert, she toured Rome, Naples, Sicily, Venice,

and then Dresden and Berlin (where they saw Bismarck and the Kaiser). In November

1889 she addressed the 2nd annual meeting of the Newcastle & Gateshead

Peace Association, on the Franco-Prussian War. The summer of 1890 saw the family

in Osen, Norway, for seven weeks. The 1891 census finds her with her family at Bensham

Grove, in a household including Robert's nephew, a cook, and two other domestic

servants. She spent five weeks with Robert in a tour of Spain, as well as a few

days in Tangier, in the autumn of 1891. In the early part of 1892 Elizabeth spent

four months with her daughter Mabel, who had been ordered south for her health,

in the Canaries. Later that year she spent six to eight weeks with Robert, at a

house called Bryn Cothi, in Caermarthenshire.32

spencewatson.jpg)

A close friend later gave a vivid picture of her at this period, appearing in drawing rooms at evening parties,

. . . with her hair braided round her head in a queenly coronal, when all the other mothers wore caps. I always see her in a beautiful robe of green plush that fell round her like moonlight. I hardly knew her in those days, but she was a most queenly figure . . .32A

She was on the Gateshead Board of Guardians for 18 years or more, which made a constant claim upon her sympathies; this work undoubtedly strengthened her temperance principles. She was one of the two women Guardians who insisted on trained nurses being employed for the first time at the workhouse. From 1889 William Moore Ede and Elizabeth Spence Watson were seen as "a formidable duo" on the Board. She retired from this position in 1913. A friend later recalled:

Her position on the Board was a difficult one; the leading members were bitter political opponents of her husband and disliked the presence of a woman on the Board. [ . . . ] Her fault, if it be a fault, was that she was too guileless and believed everyone to be as innocent as herself; consequently she did not always fathom the schemes and machinations of sinful men, and sometimes voted in support of motions which she would not have done had she perceived the ultimate purpose in view. But after all, this guilelessness and sincerity were the source of her inspiration.33

In March 1893, her children growing out of dependency, Elizabeth was again in low spirits:

The depression that comes upon me is at times almost unbearable. No little ones who must be cared for & worked for—no little feet to come running to meet one—the work that has to be of one's own choosing with the perpetual sense of "cui bono"? The strength & hope of youth gone & a constant feeling of weariness upon one.33A

In June 1893 Friends Literary Tracts published her The Wreck of the Victoria Man o' War. She spent the whole of July on holiday with her family in Wales. In July and November she had letters published in The Northern Echo, on the loss of the Victoria and the need for warships, and on the Matabele War. In December she spoke on women's suffrage, on the same platform as Millicent Fawcett. In January 1895 she had a letter on the Peace Question published in The Newcastle Daily Leader. In January 1896 she introduced the playing of chess and draughts to children in the Gateshead workhouse. In October 1896 she had a letter in the Women's Signal, on 'The Workhouse "Christmas Beer"'.33B

In 1894 she holidayed for two months in Norway, in 1895 in the Pyrenees, in 1896 in Ireland, in 1897 in Norway, and in 1898 in the Dauphiné Alps, with the family. At the end of 1898 she stayed at Studley with Robert. The summer holiday of 1899 was in Scotland, based at Oban.34

In 1895/6 she may have been the first female tutor at Durham University.34AA

In 1896 she was present at her daughter Mabel's wedding at Pilgrim Street meeting house; the reception was held at Bensham Grove. The death of the Spence Watsons' only son Arnold in 1897 was a devastating blow to the family. Elizabeth Spence Watson's 'Family Chronicles', recorded faithfully from 1864, cease abruptly, and it was fully 18 years before she could bear to put pen to paper again, to record their family life.34A

In February 1897 she was a signatory to an open letter to all members of the House of Commons, on women's suffrage. In August 1899 she went with her daughter Mary to a North of England WLA conference; she spoke beautifully, and carried a resolution against the government's proceedings in sending Britain to war with the Transvaal. In the days of the Boer War she was an active member of the local Stop-the-War Committee.35

Watercolour by Elizabeth Spence Watson, 1898, in my possession

In mid November 1899 she spent a week in York. On Christmas day that year she paid a visit to the workhouse. In January 1900, with Robert and Mary, she spent a week or two in Grange-over-Sands.36

In February 1900 signed the manifesto of the Stop the War women's group led by Sarah Amos and Jane Cobden. In June that year she attended a women's peace rally against the Boer War, at the Queen's Hall, in London.37

Robert, Elizabeth, Mary and Bertha Spence Watson, Chamonix

In August 1900 Elizabeth and Robert visited Germany, then spent September in Switzerland. She was away from home at the time of the 1901 census, but it's not clear where. With her family, she spent a month at Loch Maree, in the summer of that year. In the following year she spent three weeks in Germany followed by three weeks in Southern France. In August 1902 Elizabeth had a letter in the Newcastle Daily Leader, on 'Military training of boys'; and in March 1903 she had a letter in The Friend on 'Friends and Military Service.' In April and May 1903 she and Robert took a holiday in the Swiss Alps and north Italy, for their health. In October that year she holidayed in Ireland with Robert and their daughter Ruth. From February to April 1904 she spent ten weeks in Algeria, Tunisia, Italy and Corsica, with her sister Ruth. In July that year Elizabeth and Robert went to see a show by Buffalo Bill. The following month Elizabeth was present at her daughter Mary's wedding in Newcastle, the reception again being at Bensham. In early October she spent a couple of nights with the newly-weds in York. During this year she was beginning to suffer from varicose veins, as well as a rheumatic shoulder. In April and May 1905 she was in Teneriffe with Robert. From March to June 1906 she was in the Canaries and Madeira, with Robert, Mabel and Mary.38

In March 1906 she was interviewed by the North Mail; she expressed her regret at recent actions by militant suffragettes. In November that year, in the Daily Graphic, she noted, more sympathetically, that "it must be remembered that quieter methods have been pursued during a long course of years with apparent want of success."38A

In February 1907 she had a letter in the London Daily News, on '"In the Name of Fashion"', objecting to tight lacing. The following month she had a letter in the Newcastle Daily Chronicle, on 'Liberal Women and the Suffrage'. In April that year she spent a week at Ampleforth, staying with her daughter Mabel. She was in London for a week in May. In July, after Robert was made a Privy Councillor, many of the congratulatory telegrams to him wished Elizabeth could have been included in the honour. In August that year the family holidayed at Oldstead Hall, Coxwold. She spent the first two weeks in September with Mabel in York—the final weeks of Mabel's life.39

spencewatson2.jpg)

By October 1907 Elizabeth's health was suffering. She was very lame with sciatica, and sleeping badly. By November she was thoroughly run down, and her heart was very weak; she took to her bed, and had to have a nurse. By February 1908 she was prostrated under a bad breakdown—from the strain of months and years indeed—but improving slowly. In mid March she had had an attack of influenza, and had been in bed about six weeks, very depressed. In April she and her sister Caroline visited the Waverley Hydropathic Establishment, Melrose, Scotland. Around May and June she spent some weeks at Peebles with Robert and her nurse, still very poorly. By August, when she had been staying with the Weisses at Summerbridge, she seems to have been back on top form, as Evelyn writes:

She is wonderful. I wish you could have seen her skipping across the stepping stones yesterday & climbing stiles & railings, rushing along so that I could hardly keep up with her. She marches along, insisting on carrying her own cloak, & would absolutely spoil her grandchildren were it allowed, by waiting on them when they should wait on her.39A

In October she was in bed again, ill with an inflammation of the bladder. In January 1909 she again had influenza.40

In May 1909 she and Robert holidayed at Ventnor, on the Isle of Wight. In June she spent a couple of weeks in York, with the Pollards and the Richardsons, her daughters' families.41

At least from 1910 to 1916 she was a shareholder in the North Eastern Railway. From around 1910 until her death she was on the executive committee of the Newcastle and Gateshead Vigilance Association.42

Robert died in March 1911. She had been to him a counsellor and adviser in all that he undertook, planned or executed. He had attributed to her the enlisting of his zeal in the cause of peace. In May she acted as one of the four executors of his will, under which she inherited all his effects in Bensham Grove, as well as trust income for life.43

Almost immediately after his death Elizabeth told Mary that it was her intention to leave Bensham Grove. Nonetheless, she never did, and lived there for the rest of her own life.44

spencewatson3.jpg)

The portrait now at Bensham Grove

(with thanks to Chris O'Toole and Shirley Brown)

At the time of the 1911 census she was with her daughter Ruth and granddaughter Betty Morrell, staying in an 8 room boarding-house at 43 Carding Mill Valley, Church Stretton, Shropshire.44A

For the duration of August 1911 she stayed at Dunstansteads with the Pollards, for whose holiday there she paid. The Christmas and New Year of 1911/1912 were spent with the Morrells in York, her youngest daughter's family. In January 1912 she resigned from the chair of the WLA. In the spring of 1912 she visited the Italian lakes with the Morrells. August again saw a family holiday at Dunstansteads. In November she spent a fortnight in Manchester.45

In May 1912 she was ill with supposed gall stones. In January 1913 she was suffering from giddiness. She spent a week with the Pollards at the end of January 1913.46

In mid March 1913 she embarked for Tasmania, where she was to spend eight months with her daughter Ruth. In the summer she attended Australia General Meeting, at Adelaide. She also addressed a Woman's Christian Temperance Union meeting, speaking of the life of Josephine Butler .In October, at the age of 75, she climbed to the highest point of Mount Wellington. She was full of interest in all she saw in the new country, in the history of Tasmania and Australia, in the beauty of the scenery, the many friends who welcomed her to their homes, and in the Friends' High School, of which her son-in-law was head.47

The Richardson family were keenly interested in art, and the 400 sketches or more done on her travels in England and abroad and in Tasmania, that she left, bear witness to her skill and industry as well as to her love and appreciation of Nature. At one point she painted a series of wild flowers to adorn the great hall of the Gateshead High School. Her face would glow and her eyes shine at some beautiful sight, even to the end. It is interesting to see that, like the beauty of her character, her artistic power developed and increased, so that her later sketches are the most admirable—even those executed on her Tasmanian visit, when she was 75.48

She reached home on the 3rd February 1914, being greeted at the door by "the Jullions, Brewis, Ethel & Jane", her servants. A week later Mary took her mother to Low Fell, to arrange the hiring of a carriage for her. She settled for a 'Victoria', for £3 a week, complete with a man in livery. Her little granddaughter Caro Pollard dubbed her grandmother's Victoria "the strawberry cab", later that year.49

Before the end of April 1914 she subscribed a guinea to the Bootham Swimming Bath Fund.49A

By July Mary found her mother not nearly so strong, and "is so blind & deaf".50

By October Bensham Grove was on the telephone—no. 8, Gateshead.51

The war, of course, had begun by then. In early November the stables at Bensham Grove were commandeered by the military, for their horses. At this time she had a letter on 'The Alien Question' published in the Chronicle, protesting at the treatment of innocent Germans in England.52

Over Christmas and the new year of 1914–15 she stayed with the Morrells at the Mansion House in York. In January 1915 she had a letter in the Newcastle Daily Chronicle on 'Quakers and War'. In June that year she spent a fortnight with the Pollards at the Richardsons' home at Wheel Birks. She played patience most evenings. Mary found her to be growing sadly blind, and terribly depressed about the war. In October 1915 she had a short letter in the Newcastle Daily Chronicle on ''"The Right Road"', advocating de-escalation.53

Around 1916 she was President of the Tyneside branch of the International Arbitration and Peace Association. She spoke and wrote fearlessly against the First World War, during which her active sympathies were aroused for the Aliens (she had written to the Newcastle Daily Chronicle on 'The Alien Question' in November 1914); and at the passing of the Military Service Act she advised and helped many young men whose punishments and imprisonments she felt most keenly. One such later recalled:

In the dark and stormy days which have fallen over the world since August 1914 and in which some have seen their way to testify to convictions which have not been deemed popular I can personally testify that in no quarter did I find such steadfastness of purpose and such a rigid adherence to deep religious convictions as in Mrs Spence Watson. In the struggle for liberty of conscience I received great inspiration through her brave and noble spirit nor can I forget how, in what were to me very trying days in 1916, when friends were falling rapidly away, Mrs Watson insisted on staying with me during the long hours which preceded the hearing of my claim before the Gateshead Tribunal, the only friend I had in court.54

In mid July 1916 she spent a few days at Heugh Folds in Grasmere, on the occasion of the funeral of her sister Caroline Richardson. She made her will in August 1916, bequeathing a fifth of her estate to each of her surviving children, a fifth to the children of her late daughter Mabel Richardson, and a fifth to her son-in-law Edmund Gower; she appointed Evelyn, Percy Corder, and John Bowes Morrell her executors, each being given £50 for their service. As specific bequests she left Sir George Reid's portrait of her husband to the Laing Art Gallery, as well as such other paintings and drawings of local interest at Bensham Grove as her executors and daughters should agree; the portraits of herself and her daughter Ruth by Wickham Howard, and the furniture and pictures in her bedroom (by then the guest room) at Bensham Grove to her children, as they should agree between themselves; she left such mementoes as Evelyn should select to her sisters and their choice of her friends; £100 to each grandchild living at the time of her death; £200 to her son-in-law Hugh Richardson; £10 to each domestic servant who'd been with her for five years or more, and a sum less than £10 to each domestic servant who'd been with her for a shorter period; £10, as a mark of esteem, to each of Thomas Jameson, Walter Heathcote Golding, Thomas Rodham Hutchinson, and John J. Bramwell, employees of her late husband's law firm; £20 to her gardener, William Orient Brewis; £50 to the Gateshead Nursing Association; £100 to either the Friends Peace Association or the Northern Peace Board; £50 to the Gateshead Branch of the British Women's Temperance Association; £50 to the Newcastle and District Band of Hope; £100 to the Committee of the Friends High School Hobart Tasmania; the residue to be divided in fifths as previously stated.

She spent December of 1916 at Wheel Birks. December the following year she spent at York, a week with each of her daughters resident there. After the February 1917 revolution in Russia she wrote to Peter Kropotkin, welcoming the news; he acknowledged his regret that they couldn't share the joy with her late husband; In February 1918 she was present at the celebratory luncheon to Emma Richardson Pumphrey.55

Her clear vision of right and wrong was unerring. Her eyes would flash with indignation, and she spoke out without hesitation against what she felt to be wrong. Offered once by a visitor a tortoiseshell tea-caddy looted from the Palace at Pekin, she flashed out, "Take what you stole, Never!" In these last years her face became irradiated with a love and peace and spiritual beauty which those who saw could never forget. John Morley said he had never understood the meaning of the words 'the beauty of holiness' until he became acquainted with Elizabeth Spence Watson. She had great faith in prayer; after breakfast she would read a short passage, usually from the Bible. She did not talk much about religion, but one felt it was religion which was the root of her character, and that it was the peace of God which ruled in her heart.56

In 1948 her servant, Brewis, looked back thirty years, and recalled:

Mrs Spence Watson was so kind & thoughtful & in my last year there I shared the Double bed room with Mrs Spence Watson as she wanted company at night & I felt very proud that I had been asked to sleep in the same room & I did every thing for her even to helping her to get her bath & bandage her legs which had to be done every morning, she was always so sweet & most grateful & never grumbled at all & she was very poorly then but would concent to have a nurse until I was leaving to be married . . .57

At the end of July 1918 she was suddenly taken ill with her heart, suffering agony at first, though recovering during the following week. In August 1918 she took a Miss Barringer as her companion, the latter taking up her duties at the beginning of September after Elizabeth had suffered a bad fall, bruising her face against the metal of her bedstead. On the 29th September she was well enough to walk to meeting, but apparently overtaxed herself or caught a chill after sitting at home with the fire out (because of coal rationing), and suffered a heart attack the following day. In considerable pain, for which she took morphia, she remained in bed till at least mid-November, fighting not only the pain but depression. On Armistice Day, 11th November, she had the Bensham flag raised, and herself summoned the strength to walk down to lunch.58

She was a robust Liberal (though not renewing her subscription during the war), keenly interested in the extension of the suffrage, especially to women; only a few months before her death she presided at a large meeting on Tyneside to celebrate the limited extension of 1918; she was a pioneer of the women's movement in the North of England. For Ann Craven, author of the only academic study of Elizabeth Spence Watson to date, "she was unusual in maintaining a holistic belief in peace and women's suffrage."59

spencewatson_1919.jpg)

Elizabeth Spence Watson. c. 1918

She was a consistent and fearless champion of peace between nations and between classes; she was a most delightful and inspiring friend of all kinds of people; she never kept silence when the cause of truth demanded her assistance. To the hospitalities of Bensham Grove she contributed no little of their peculiar grace and charm.60

She had a high-souled nature, and was a keen lover of justice and gifted with an untiring zeal in the furtherance of all good causes.61

To both Robert and Elizabeth children were a great joy, and in later years their grandchildren were their greatest comforters in sorrow. Elizabeth loved to have her grandchildren with her even to the end, and 'Grannie' was beloved by them all.62

Towards the end of January 1919 she fell gravely ill, and it became clear that it was her final illness. However she lingered a fortnight more, at times in great suffering, sedated with morphine, sometimes delirious, but sometimes tranquil. It was a time of enormous distress to the family, as indeed it was to herself. On the 5th February she had a further heart attack, and it was doubtful whether she'd survive the night. She was unconscious from the 10th February, then at five o'clock on the 14th February, just as her daughters were sitting down to tea at Bensham Grove, they were summoned upstairs, where they arrived just in time for their mother's last moments of life. She died of atheroma of the coronary vessels and pyelitis 19 days. Her sister described her face in death as "calm and untroubled and peaceful." Her body was buried in the Jesmond Old Cemetery, Newcastle, at 1:30 on Monday the 17th. Theo Merz gave a fine eulogy at the meeting after the funeral, after which the family withdrew to Bensham, where sketches and photos were spread out. At the probate of her will on 23rd October 1919 her effects were valued at £6812.10.8d (£144,494 at 2005 values). The notice of her death in the Northern Echo bore the headline "GREAT LOSS TO THE NORTH".63

In 1920, as her sister Alice noted, the Annual Monitor "contains a very perfect little memoir of Lizzie—we wonder who has written it."63A

Elizabeth Richardson was the fifth child and third daughter of [O2] Edward and [P1] Jane Richardson.64

1 birth certificate; Annual Monitor 1919–20

2 TNA: HO 107/824/10 f21 p34; TS Reminiscences of Elizabeth Spence Watson; Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson; Herbert Corder: 'Elizabeth Spence Watson': 1. Augusta Richardson's Reminiscences say, of Mrs Gething's school, that her "small class was held at her house in Westmorland Terrace, of which one side was newly built and looked across brickfields and down to the Shot Tower and the River. Here we went daily to school for I think about three years. Mrs Gething was a highly educated and very interesting woman, but more fitted to have taken girls of 16 or 18, and not severe enough in grounding us in the dull foundations. Each afternoon she spent chiefly in reading or relating to us some elegant passages from the poets, dilating on its beauties and with much impressing elocution etc. For instance, one afternoon she would give us 'A Mother’s Love' read passages and poems, and tell of incidents and stories bearing on the subject and so on. Another day, we were given Paul’s speech before Agrippa, and a contest for a prize to who should say it best. Eliz Watson got the prize, now Mrs Spence Watson."

3–4 Annual Monitor 1919–20

5 Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson: 24, TS Reminiscences of Elizabeth Spence Watson

6 TS Reminiscences of Elizabeth Spence Watson

7 TS Reminiscences of Elizabeth Spence Watson; Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson: 35

8 HO 107/2404 f469 p57; Annual Monitor 1919–20; TS Reminiscences of Elizabeth Spence Watson; Ann Craven (2004) 'Elizabeth Spence Watson: a Quaker working for peace and women's suffrage in nineteenth century Newcastle and Gateshead' , MA dissertation, University of Newcastle upon Tyne

9 TS Reminiscences of Elizabeth Spence Watson

10 TS Reminiscences of Elizabeth Spence Watson, Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson

10A diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms)

11 Dictionary of Quaker Biography

12 TNA: RG 9/3815 f47 p2; Minutes of Newcastle Preparative Meeting (Women's) 1834–1878, Tyne & Wear Archives Service MF 194; Richardson private ledger, TWAS Acc. 161/330; Robert Spence Watson collection, House of Lords RO Hist. Coll. no. 136; marriage certificate; Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson: 159

13 minutes of Newcastle Monthly Meeting 1861–67, TWAS MF 170; Richardson private ledger, TWAS Acc. 161/330; family documents now at TWAS; Joseph Foster (1871) A Pedigree of the Forsters and Fosters of the North of England; marriage certificate; front papers to my copy of Percy Corder (1914) The Life of Robert Spence Watson. London: Headley; Reminiscences of Robert Spence Watson; Corder (1914); Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"; The Friend 1863-08-01 p. 196, The British Friend 1863-07-01 p. 181; Alpine Club Register: 368–9; Ms journal of their wedding tour

13A Newcastle Journal, 1863-06-10; Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury, 1863-06-13

14 Dictionary of Quaker Biography; The Friend IV:146 1864-06-02, The British Friend 1864-07-01; children's birth certificates

14A Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles";

14AA Newcastle Journal, 1863-11-27

15 TS Reminiscences of Elizabeth Spence Watson

16 Evelyn Weiss: Ms Foreword to TS RSW Reminiscences

17 Reminiscences of John Theodore Merz. London: Blackwood (privately printed), 1922: 255

17A Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"

18 Reminiscences of Robert Spence Watson; John Wigham Richardson: Memoir of Anna Deborah Richardson Newcastle 1877: 251; Catalogue of Tyne & Wear Archives Service; William K. Sessions: They Chose the Star. 2nd edn 1991, York; Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"; letters from Elizabeth & Robert Spence Watson to Jane, Caroline and John Wigham Richardson, now at TWAS

19 RG 10/5051 f63 p24—the enumerator gives the street name as "Leasham" Lane; Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"

20 Reminiscences of Robert Spence Watson; RSW & ESW letters now at TWAS; Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"; RSW in Wayside Gleanings

21 Mosscroft visitors' book; The Friend NS XIV.Aug:273; daughter's birth certificate; RSW & ESW letters now at TWAS; mother's will and grant of probate

21A Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"

22 Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"

22A letter from Robert & Elizabeth Spence Watson to Mabel Spence Watson, TWAS Acc. 213/25; Corder (1914); Reminiscences of Robert Spence Watson; Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"

23 Reminiscences of Robert Spence Watson

24 E. Spence Watson: Notes to RSW Reminiscences; Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"

25 RG 11/5033 f97 p14

26 E. Spence Watson: Notes to RSW Reminiscences; Three holiday journals, 2 by ESW & 1 by RSW, formerly held by Mabel Weiss; catalogue of Tyne & Wear Archives Service; Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"

27 Corder (1914); DQB; Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"; Sansbury, Ruth: Beyond the Blew Stone. 300 Years of Quakers in Newcastle. 1998: Newcastle-upon-Tyne Preparative Meeting; Marriott, Dan (2002) 'Robert Spence Watson. A Pioneer of Education in the North' , University of Durham MA dissertation.

28 front papers to my copy of Corder (1914); Sansbury, Ruth: Beyond the Blew Stone. 300 Years of Quakers in Newcastle. 1998: Newcastle-upon-Tyne Preparative Meeting.

29 Reminiscences of John Theodore Merz. London: Blackwood (privately printed), 1922: 280

30 'Newcastle-upon-Tyne Women's Liberal Association 1886–1911', by Elizabeth Spence Watson; front papers to my copy of Corder (1914); Google Books; Dictionary of Quaker Biography; Craven, Ann (2004) 'Elizabeth Spence Watson: a Quaker working for peace and women's suffrage in nineteenth century Newcastle and Gateshead' , MA dissertation, University of Newcastle upon Tyne

31 DQB; Craven (2004); Elizabeth Crawford (1999) The Women's Suffrage Movement, London: Routledge, p. 702; To the Arctic Zone, reprinted from Free Russia; Lara Green (2019) 'Russian Revolutionary Terrorism in Transnational Perspective: Representations and Networks, 1881–1926', 2019 PhD thesis, University of Northumbria

32 letter to Mabel Spence Watson, TWAS Acc. 213/249; three holiday journals, 2 by ESW & 1 by RSW, now at TWAS; Corder (1914); Evelyn Weiss: Ms Foreword to TS RSW Reminiscences; catalogue of Tyne & Wear Archives Service; RSW & ESW letters now at TWAS; Reminiscences of Robert Spence Watson; RG 12/4176 f60 p46; Diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"; The Friend XXIX Mar:Ads 15; UK outward passenger lists

32A Herbert Corder: 'Elizabeth Spence Watson': 1; letter to Mabel & Mary Spence Watson, TWAS Acc. 213/258; letter to Mabel Spence Watson, TWAS Acc. 213/261; letter to children, TWAS Acc. 213/262

33 Annual Monitor 1919–20, Northern Echo 15 Feb 1919-02-15, The Friend LXIX:133–5 1919-03-07; F.W.D. Manders (1973) A History of Gateshead; the Newcastle Chronicle of 1889-04-02 records that her nomination for the Board of Guardians had been ruled out of order, on the ground that her name didn't appear in the rate book, where an official had altered the name 'Robert' to 'Elizabeth', apparently without their knowledge. In October 1896 she had a letter in the Woman's Signal, contesting the convention by which beer was given to workhouse inmates on Christmas Day [Woman's Signal, 1896-10-15]

33A Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"

33B Craven (2004); RSW Cuttings; Diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard

34 RSW & ESW letters, and postcard from Evelyn to Elizabeth Spence Watson, now at TWAS; diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); Mary Spence Watson, Commonplace Book; The Journal of John Wodehouse First Earl of Kimberley for 1862–1902: 463; E.S.W. 'South-West Donegal', Westminster Gazette 1896-10-08; ESW sketchbook

34AA The North's Forgotten Female Reformers, citing the 1895/96 Principal's Annual report (NUA/3/1/1, University Archives)

34A Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"; RSW Cuttings

35 The Guardian 1897-02-02; diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms), The Friend 60:133-4 1919. Curiously, a graphologist reported, in the St James's Gazette [1897-02-16], on the handwriting of the signatories to the suffrage letter: "'Elizabeth Spence Watson' is a plan straightforward hand." Her signature had not been written with a quill.

36 diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms)

37 Westminster Gazette, 1900-02-10catalogue of Tyne & Wear Archives Service

38 E. Spence Watson—watercolour sketches possessed by me; Diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms), ESW: Album/holiday itinerary, now at TWAS; catalogue of Tyne & Wear Archives Service; letters of Mary Pollard; Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"; The Friend XLIII:156–7; RSW Cuttings; Frank and Mary Pollard visitors' books; letters from Elizabeth Spence Watson to Molly Richardson, 1901-09-16, 1905-04-09, and postcard, 1905-05-14, possessed by Paul Thomas; letter from Ruth Spence Watson to Molly Richardson, 1904-02-28, possessed by Paul Thomas

38A Craven (2004); RSW Cuttings

39 diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); catalogue of Tyne & Wear Archives Service; Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"

39A diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); letters from Frank Pollard; letter from Evelyn Weiss to Robert Spence Watson, now at TWAS; letter from Caroline Richardson to Molly Richardson, 1908-04-04, possessed by Paul Thomas; letter from ESW to Molly Richardson, 1908-04-27, possessed by Paul Thomas

40 diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); letters from Frank Pollard

41 diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); Frank and Mary Pollard visitors' books

42 diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"; NGVA leaflet in my possession

43 Annual Monitor 1919–20, The Friend 51:164-7 1911; Robert Spence Watson's will, codicil, and probate

44 diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); will; index to wills and administrations, Principal Registry of the Family Division; death certificate; Annual Monitor 1919–20

44A TNA: RG14PN15924 RG78PN980 RD344 SD1 ED1 SN131

45 diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); Craven (2004)

46 diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); Frank and Mary Pollard visitors' books

47 diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); DQB; Annual Monitor 1919–20; RSW & ESW letters now at TWAS; Corder (1914); The Friend LIII:524–5, 869; Frank and Mary Pollard visitors' books; Wikipedia, citing The Mercury (Hobart), 1913-09-12

48 Annual Monitor 1919–20

49 diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms)

49A Bootham 7.1:76, May 1914

50 letters from Ruth Gower to Mary Pollard

51 letters from Elizabeth Spence Watson to Mary Spence Watson (Pollard)

52 diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 1914-11-04

53 diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms)

54 Annual Monitor 1919–20; letter from R.W. Ridley to Evelyn Weiss, now at TWAS; MSWP album of cuttings, in my possession

55 entry by ESW in Heugh Folds visitors' book, in possession of Elizabeth Ryan; will; letters from Frank Pollard; Elizabeth Spence Watson's "Family Chronicles"; Ms Recollections of Emma R. Pumphrey, TWAS Acc. 474/11; Frank and Mary Pollard visitors' books; Green (2019)

56 Annual Monitor 1919–20:294-5, Joseph Foster (1873) Pedigrees of the County Families of England, Vol.1, Lancs.; Mary S.W. Pollard: 'A Few Reminiscences', TS; The Friend 60:133-4 1919

57 letter from Gertrude Brewis to MSW, 1948

58 letters from Elizabeth Spence Watson to Mary Spence Watson (Pollard); Diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms)

59 Northern Echo 15 Feb 1919; The Friend 60:133-4 1919; Diaries of Mary S.W. Pollard (Ms); Craven (2004)

60 Northern Echo 15 Feb 1919; The Times 3 Mar 1911

61 Corder, op. cit.

62 Annual Monitor 1919–20

63 letters of Mary Pollard; Annual Monitor 1919–20; death certificate; DQB; Northern Echo 15 Feb 1919; Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 1919-02-17; front papers to my copy of Corder (1914); will and probate; The Friend LIX:116 1919-02-21; Alice Mary Merz, 'Family Notes', typescript

63A Alice Mary Merz, 'Family Notes', typescript

64 RG 6/404, /1149; GRO index

## NB There are literally hundreds of references to "Mrs Spence Watson" in the British Newspaper Archive; I have not yet worked through these. ##

Tyne & Wear Archives, and Newcastle University Library, have considerable numbers of letters, to and from numerous correspondents, that I have not had the opportunity to read. TWAS also has a collection of condolence letters on ESW's death.

The Bodleian Library has half a dozen ESW letters to James Bryce.

A memoir of Mabel Spence Richardson, by ESW, is held privately, as are considerable numbers of her watercolours.

Edward Richardson was born on the 12th January 1806, in St John's parish, Newcastle. Though his father died when he was only four, he found a second father in his uncle George Richardson. He was always delicate—he suffered from asthma—and this made him an object of care and tender solicitude to his mother, to whom he was ever a dutiful and affectionate son.1

At the usual age he was sent as a day-scholar to John Bruce's school, where he was a favourite with his master, who considered him clever. For his age he excelled in Greek, which at that time was not much studied in day schools. After a few years he was sent to Frederick Smith's school at Darlington, which ranked as a first-class school among Friends, where he was placed among the older pupils in the classroom with young men who had almost a collegiate training, under an able professor from the University of St Andrews: he made satisfactory progress in his studies, and took a good position as a classical scholar. On his return home he used to enjoy reading Greek with Robert Foster (sr).2

On leaving school he worked as an apprentice in the tanyard in Newgate Street established by his father, in which he afterwards became a partner. As a young man he was fond of intellectual and scientific pursuits, and enjoyed entertaining his young friends with experiments in electricity and pneumatics. Many a happy evening was spent in this way. He had a decided aversion to metaphysics, considering that the human intellect when turned too much inwards, was apt to prey upon itself. His highly practical mind led him to prefer natural science to abstract. He took a kind interest in the apprentices of the tanyard, ten or twelve in number, whom he used to invite to his home, where he read to them, and showed them experiments with the electrifying machine and air pump. His tendency to pulmonary disease prevented his close attention to business, but his manner towards the workmen and apprentices was refined and courteous, and he was much beloved by them.3

In July 1825 he attended Quarterly Meeting at Sunderland with his brother, whose letter gives an account:

About 35 friends embarked on board the "Britannia" of two engines of 25 horse each, on second day morning at ¼ before eight, reached Shields at ¼ before 9, where 17 friends joined us, and Sunderland pier at ½ past 10, where 14 more made up the company. A fine, warm, westerly breeze, smooth sea, and smile on every face rendered the voyage delightful. We formed into social groups, or noticed the progress by the land objects, or pointed out the ships scattered about us, or paced the deck as inclination led us.

At the mouth of the Tees we took in Wm. Aldam and family for a short time, who are Friends from Leeds staying at Seaton, and who gave about a dozen urchins or sea-hedgehogs amongst us which they had been fishing for. As the tide had not risen sufficiently high we sauntered at the mouth of the Tees some hours, where a group of seals and a variety of sea birds interested us. We reached Stockton Quay a little after 6.

On third day night the wind had removed to the North-east, yet so little of it that friends embarked at ½ past eight on fourth day morning, without the slightest apprehension. We sailed finely down the Tees about 13 miles, but as we approached the sea the pilot, we took in, a little excited our fears by telling us he must go on to the Tyne as he could not re-land with his small boat on the coast for the breakers. As we got out to sea one after another fell sick. We stood against the wind, which was quite contrary, for some hours; the day was cold accompanied with small rain, which rendered it uncomfortable, yet only 3 or 4 of those quite knocked up went down to the cabin, of which poor brother Edward was one. In attending to him and getting him to bed, I fell sick, yet chose to lay on the deck. At last the captain not choosing to risk of anything giving way with such a valuable cargo on board, put back to Hartlepool, where we were all safely landed. The next consideration, after an unrelished cup of tea, was to get homewards. Wm. Aldam kindly sent his carriage with some, besides which there were 6 fish carts engaged for the "sick, the women, children and baggage." After doing what we could to provide for our female friends, brother and I set off to walk, and reached Sunderland at ½ past 9 last night, 23 miles—thinking walking most likely to relieve our sickness, which indeed we found was the case. There were other companies of walkers, but as we set off between the carts, expecting they would overtake us, did not fall in with them. We left Sunderland at 5 this morning. Charles Bragg and I to Newcastle and my brother to Tynemouth. The "Britannia" is still lying weather bound at Hartlepool. The account of this curious journey has taken up so much room that I cannot give much detail of our Quarterly Meeting. It occasioned in this short journey a great mixture of pleasure and profit, as well as of toil or trouble than I ever met with, though I think upon the whole the novelty of riding in fish carts gave a kind of social enjoyment that was not disagreeable.4

In April 1826, with John Richardson, Edward was one of the founding twelve members of the Newcastle Book Society. He joined the Newcastle Lit. & Phil. in 1828. In April 1827 he was one of two representatives from Newcastle to Monthly Meeting, held at North Shields. In August that year, described as of Spring Gardens, he donated ten guineas to the Newcastle Dispensary. In 1828 Edward served three times as representative to Monthly Meeting, in January, September and November. In October he was listed as one of the trustees for the meeting house and burial ground.5

In

April 1829 he inherited his grandfather

David Sutton's house on Princess Street, of which he was already in

occupation, together with £500 and ¼ of the furniture and effects. With his

brother John, he was executor of David Sutton's will; each executor was paid

£30.6

In

April 1829 he inherited his grandfather

David Sutton's house on Princess Street, of which he was already in

occupation, together with £500 and ¼ of the furniture and effects. With his

brother John, he was executor of David Sutton's will; each executor was paid

£30.6

In his early twenties he sought the friendship of [P2] John Wigham's only daughter. The fame of her talents and accomplishments made an attempt to obtain her hand a somewhat anxious task. His visits to Edinburgh were times of great interest in the family circle. It was before the time of railways. The Richardson house stood by the North road, and the 'Chevy Chase' coach passed their gate, and when it stopped to take him up, the little household would turn out to bid this beloved brother good speed on his important errand. At the beginning of March 1830 Newcastle Monthly Meeting appointed James Gilpin, Robert Spence and John Mounsey to enquire into Edward's clearness for his proposed marriage to Jane Wigham, which proved uncontentious. On the 28th April 1830 he married [P1] Jane Wigham, at Edinburgh Friends' meeting house. Edward and Jane's children were: Anna Deborah (1832–1872), Caroline (1834–1916), Edward (1835–1890), John Wigham (1837–1908), [O1] Elizabeth (1838–1919), George William (1840–1871), Isaac (1842–1846), Jane Emily (1844–1903), Alice Mary (1846–1933), Ellen Ann (1848–1925), and Margaret (1851–1855); all births were registered by Durham Quarterly Meeting.7

In June 1830 Edward was one of four representatives from Newcastle to the ensuing Quarterly Meeting at Darlington. In July and October he was one of two Newcastle representatives to Monthly Meeting, as he was in June and September 1831, February, October and December 1832, October 1833, and March 1834 (in February 1832 his co-representative was Joseph Watson). In July 1831 he was one of 45 men Friends who signed the certificate for George Washington Walker. In 1833 Edward was a member of the Essay Society in Newcastle, to which he contributed a poem on the forthcoming Aurora annual. His poem was "much remarked upon as very original metre, or no metre at all but irregular verse." In April 1834 he became an annual subscriber of 10s. to the Gateshead Institution for training Female Servants. That year he served on the main committee, and as a teacher, at the First Day School, to which in May he gave four books, a Bible, and a reference testament, as well as £1 from his brother and himself; by 1840 he was no longer teaching.8

On his marriage he had taken up his residence at Summerhill Grove, then a country suburb of Newcastle with an uninterrupted view of Ravensworth and the valley of the Tyne. The 1832 electoral register shows him there, qualified to vote by virtue of his share of freehold houses and land at Spring Gardens, then occupied by his mother and others. The 1833–4 Newcastle directory shows the family home at 6 Summerhill Grove; the tannery, in which he was now, with John Richardson, a partner, was located at 66 Newgate Street—they were described as tanners, morocco leather dressers and glue makers. The 1835 electoral register entry replicates that of 1832. In 1836 the tannery was described as being at the White Cross, Newgate Street.9

In January, February, March, May and September 1835 the tannery cashbook records £100 payments to him, as well as an additional payment in May of £272.15.–. In March 1835, with Henry Brady, he was appointed by the Monthly Meeting to ensure that the marriage of Joseph Watson and Sarah Spence was conducted agreeably to good order, and to prepare abstracts of the marriage certificate. Described as a tanner of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, he was a witness at the marriages of Sarah Spence and Joseph Watson, and Mary Spence and James Watson.10

In February 1836 the tannery paid him £150, in June £126-19-1, and in October £60, on the latter occasion with the annotation "To Torquay." The cashbook shows that the partners had accounts with the Northumberland & Durham District Bank, Sir M.W. Ridley & Co., bankers, and the Newcastle branch of the Bank of England. In 1836 he was a signatory to the deed of settlement of the Northumberland and District Bank—to his later cost.11

At the beginning of 1837 he wintered with his family in Torquay, on account of his delicate health. His brother and partner John kindly and willingly liberated him, whenever it was thought desirable, on health grounds, for him to leave home. He took many journeys for the benefit of his health, both by sea and land, often accompanied by his sister Ann. On one of these occasions they were shipwrecked. In 1837 they went to London by the Menai steamer to consult Sir James Clark, who recommended him to return home by a sailing vessel. Accordingly they embarked in a Newcastle trader, The Bywell, making her first voyage. The weather was threatening, and the captain crowded on all sail; hoping to have light enough to run into Yarmouth Roads and shelter for the night. But the storm of wind and rain increased. Edward and Ann were alone about six o'clock in the cabin, fearing no danger, when suddenly there came an awful shock, quickly followed by another and another. The vessel had struck upon the Newcombe Sands off Pakefield, and all hope that the ship would get off was taken away, for the rudder was soon lost, and she seemed to be breaking up by the violence of the waves. The men prepared to launch the boats; the first was swamped in the attempt, and the long boat shared the same fate. They were three miles from shore. They were about three hours in this state of exposure and uncertainty, when the lifeboat from Lowestoft, with seventeen brave men, came to their rescue. Just a quarter of an hour afterwards the ship broke up. Edward lost everything except the clothes he wore. They reached the shore at about ten o'clock at night, where they received most kind attention from the Vicar of Lowestoft, Francis Cunningham, and his wife, one of the Gurneys of Earlham [Richenda, sister to Elizabeth Fry and Joseph John Gurney]. He took them to their house, and kindly sent them on to Norwich in their carriage to take coach for the North. In November 1837 Edward doubled his subscription to the Shipwreck Society.12

It was in 1837 that the politician John Bright first met his future wife, Elizabeth Priestman, at Edward Richardson's house in Newcastle.13

In 1838 he was still living at 6 Summerhill Grove, a tanner in the partnership of John and Edward Richardson, tanners, Morocco leather and glue manufacturers, of 66 Newgate-street. In July 1838 he donated £2 to the Reception Fund for the Newcastle meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. That month he also subscribed £2 to the Royal Victoria Asylum for the Blind; in August that year he subscribed £10, and an annual subscription of 10s. 10d., to the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Zoological and Botanical Society, and in September he gave a second subscription of £5 to the Newcastle Female Penitentiary. In December he donated a guinea to the collection for the children of Joseph Millie, who had been murdered in the Savings' Bank. In January 1839 he was co-signatory with John and others to an open letter to the Mayor of Newcastle, requesting that he call a public meeting with a view to petitioning Parliament over the corn laws. That month, too—doubtless to reflect his experience the previous year—he subscribed £5 to the Infirmary at Lowestoft, enlarging for the benefit of ship-wrecked sailors. The following month his tannery advanced the wages of the tanners in their employment, in consequence of the high price of provisions. In January 1840 he donated £1 to the Newcastle Total Abstinence Society's scheme for the monthly distribution of a temperance publication to every family in the town. In February that year John & Edward Richardson, of 66 Newgate-Street, advertised for sale the house and garden called Spring Gardens, with outhouses and stables, the whole containing nearly an acre. By September 1840 he had subscribed £1.1s. to the Newcastle Teetotal Society.14

The 1841 census recorded Edward Richardson as a tanner of Summerhill Grove, Westgate, Newcastle, living with his wife, six children, and four female servants. In 1841 he went to spend the winter at East Law (now Derwent Hill), Ebchester, a house belonging to his brother, John Richardson. That year he subscribed £1 to the North of England Agricultural School. In May 1842 he was one of 2 representatives from Newcastle to Monthly Meeting, as he was in June and December 1846. In 1843 he was Treasurer of the (Newcastle) Peace Society, as he was again in 1849. In 1844, at the request of miners of Northumberland and Durham, he signed an open letter to the Marquess of Londonderry, regarding the pitmen's strike. In 1845, in the will of his wife's uncle Anthony Wigham, he was described as a currier of Newcastle on Tyne. In February 1846 he and his brother were listed as shareholders in the Stockton and Durham County Banking Company. In the summer of 1846 he holidayed with his family with John Wigham, partly at Edinburgh, and partly by the seaside, at the village of Dirleton, not far from the Bass Rock.15

Around 1846, when George Catlin's Indians came to Newcastle—a dozen Sioux men, one woman with a baby and a lad some twelve years old—they all came to tea one afternoon; later he called on them at their lodgings. In December that year he was present at the death of his son Isaac, at Summerhill Grove.16

The 1847 directory still shows the partnership of Edward and John Richardson, tanners and glew manufacturers; but by that year Edward's nephew James Richardson had taken over from his father as partner.17

In the summer of 1847 he took lodgings, with the family, at Whitburn, a charming seaside village a little north of Sunderland.18

Around 1847, one dark night in the Christmas holidays he took his four elder children to see Lord Armstrong, (then Mr William George Armstrong, solicitor), exhibit his electrical machine. He himself had made a very good electrical machine which was often got out in the evenings and experiments performed. This was later presented to the Gateshead High School for girls.19

When his large family were growing up around him, he was very watchful over them; he enjoyed mingling with his children in their pursuits, and taught them to be brave and daring, encouraging a spirit of self-reliance. It was his desire to train up his children in the principles of the Society of Friends, to which he was himself sincerely attached. He was fond of horseback exercise himself, and trained them when young in the love of it; his manner towards them was gentle and kindly. He had a large wagonette (they called it the car), in which he used to drive his family to various points of interest—once, around 1849, along the Roman Wall. He was always fond of horses—he kept two saddle horses—a nearly thoroughbred mare called Fanny, and (in 1856) a horse called Minniehaha.20

At Monthly Meeting in Newcastle, in January 1848 he signed the testimony to Rachel Wigham; and in September that to Daniel Oliver. In November of 1849 Edward was stated to be Treasurer of the Newcastle Peace Society.21

By 1850 the partners in the tannery had established the Elswick Leather works, in Shumac Street, Newcastle. In November that year he was listed as one of two men to whom Newcastle Friends should apply if they wanted a gravestone.22

In March 1851 Monthly Meeting recorded Edward as one of the trustees of Friends' property; he represented Newcastle at Monthly Meeting in April and September. The census that year recorded him as a tanner master, living at 6 Summerhill Grove, Westgate, Newcastle, with his wife, seven children, two housemaids and a cook. In the summer holidays of 1851 Edward took Caroline and John Wigham Richardson to see the Great Exhibition, taking lodgings in Sloane Square for the occasion. In September 1851 he made a benefaction of £20 to the Newcastle Infirmary. In November he gave an address to the Westgate Temperance Society, chiefly on the evils of increasing the number of public houses by granting new licences.23

6 Summerhill Grove was too small now for the large family, so Edward arranged to leave the house at the May term of 1852 and to reside at Beech Grove. When the May term came, the house was far from being ready, so he took Nab Cottage on the shores of Rydal Water for the whole summer. There had been some thought of going to Ullswater but it was considered essential to be within reach of a Friends' Meeting. In mid 1852 the family left 6 Summerhill Grove, moving to Beech Grove, Elswick Lane—a house and 16 acres. The total rent for Beech Grove was £180 which, taken at 4%, gives a value of £4500.24

Emma R. Pumphrey, in later life, recollected of this period: