richardson.jpg)

| ↳ other children

| ↳ other children

Jane Wigham = Edward Richardson

| ↳ other children

Elizabeth Richardson = Robert Spence Watson

| ↳ other children

Mary Spence Watson = Francis Edward Pollard

Jane Wigham was born at Lothian Street, Edinburgh, Midlothian, on the 19th March 1808. She was an only child (although adulthood saw the arrival of half siblings), so may have experienced a degree of loneliness, but her childhood, with its friendships and intellectual pursuits, was described as very happy. A Miss Macgregor, in 1859, reminisced, having known her when she was a little girl, that "Everybody used to love Jane so much!" She studied Latin as a child, and used to read Horace together with her close friend Sarah Rickman. When she was young, the only novel ever allowed was Hannah More's Coelebs in Search of a Wife—no music, no dancing,—just the thin end of drawing. Clearly, history and philosophy would be quite amusing in lives so restricted. They were read pretty largely, and instead of amusements, were hospitality and 'good works.' She read every book in John Wigham's excellent library, and some more than once. With an extremely retentive memory, she seemed, in her after life, to have all these books in different languages in her head, and, being of an ardent poetic nature—from childhood she had a real gift for poetry—she infused a desire for knowledge into her children's minds, and set before them a high standard by which to measure their progress.1

She married [O2] Edward Richardson at Edinburgh Friends' meeting house on the 28th April 1830. At this time Jane's father, John Wigham, gave her £6133, to include £3000 which he regarded as due to her in right of her mother's estate. The balance was to prove much greater than he was able to offer the children of his second marriage, in the light of his reduced circumstances, and she was accordingly all but written out of her father's will. Edward and Jane's children were: Anna Deborah (1832–1872), Caroline (1834–1916), Edward (1835–1890), John Wigham (1837–1908), [O1] Elizabeth (1838–1919), George William (1840–1871), Isaac (1842–1846), Jane Emily (1844–1903), Alice Mary (1846–1933), Ellen Ann (1848–1925), and Margaret (1851–1855); all births were registered by Durham Quarterly Meeting. She most conscientiously performed the duties devolving upon her as wife and mother, and as mistress in the household. Though the uncertain and delicate health of her husband was a source of great anxiety to her, the education of her children claimed her earnest care.2

She had much intellectual ability, and was believed to have been a contributor to the Aurora Borealis, under a nom de plume. In 1832 and 1833 she was a member of the Essay Society in Newcastle. In November 1833 she subscribed 10s. annually to the Union School for poor girls in that town. In April 1834 she was on the first committee for the local Friends' sabbath school and in May, with Edward, donated £1 to its library. In June 1834 and August 1838 she attended Monthly Meeting as one of two representatives from Newcastle Women's Preparative Meeting.3

In the 1830s she lived at Summerhill Grove, in Westgate, St John's parish, Newcastle. She was recorded there with her husband, six children, and four servants, in the 1841 census.4

She had a great power of sympathy with the troubled and anxious, and to the young, the aged and the poor she was constantly ready with kind counsel and help. Even strangers were so drawn to her that, almost before they were aware, they told her their troubles. James Montgomery, the poet, had in 1837 established in Newcastle, a Society for visiting aged women. She took one of the poorest districts in the town, and continued diligent in the work till her increasing blindness rendered it impossible. The love and reverence which these poor people felt for her arose not so much from her gifts as from the loving sympathy which she showed them as fellow human beings.5

In March 1845, of Summerhill Grove, she was elected to a committee of ladies to support the projected National Anti-Corn Law League Bazaar, to be held in London that May.5A

The reference to her blindness stems from an incident while on holiday at Whitburn in 1847, when there was a terrific thunderstorm, and a vivid flash of lightning which made her, when driving in her phaeton, quite blind for several minutes. Her eyesight was never perfectly right again.6

richardson.jpg)

From June to October 1847 Jane Richardson was authorised to receive contributions to a "Box of Ladies' work, and other contributions", being sent by the Edinburgh Ladies' Emancipation Society to the 14th Annual Anti-Slavery Bazaar at Boston, Massachusetts, during the Christmas week, "for the purpose of aiding the Cause of the Slave, by expressing sympathy with the labours of American Abolitionists, and raising funds for the Massachusetts Female Anti-Slavery Society." Jane and her step-daughter Elizabeth were the leaders of this Edinburgh Society. Of 6 Summerhill Grove, by November 1848 she was acting as Secretary to the Newcastle Ragged School for Girls, due to open on the 20th of that month; she had taken out an annual subscription of £1. In July 1849 she was again authorised to receive, at Summerhill Grove, donations for the Anti-Slavery Bazaar.7

In June 1840, March 1847, December 1849 and March 1853 she attended Monthly Meeting as one of two representatives from Newcastle Women's Preparative Meeting. In September 1848 she signed the Monthly Meeting testimony to Daniel Oliver. In early January 1850 she was one of the women who presented a purse of twenty sovereigns to William Wells Brown, the guest at an anti-slavery soirée at the Music Hall in Newcastle. The 1851 census recorded her living at 6 Summerhill Grove, Westgate, Newcastle, with her husband, seven children, two housemaids and a cook. In May 1851 Jane was Secretary to the Newcastle Ladies' Anti-Slavery and Free Produce Association.8

During the 1853 epidemic of Asiatic cholera in Newcastle, most of the well-to-do inhabitants left the town and took up their quarters at Harrogate and such-like places, but she thought it her duty to remain, and daily visited the poor people of her district, and she was fearless in visiting the worst houses. The cholera outbreaks in Newcastle were centred around Sandgate, which was not only worst for poverty, but was perceived as dangerous—claimed by The Builder to be worse than Cairo.8

In the summer of 1856 she stayed with the children at Ardrossan. In September 1854, March 1857, and May 1860 she attended Monthly Meeting on behalf of Newcastle Women's Preparative Meeting.10

In January 1857 Jane was re-elected as Secretary to the Ragged School for Girls.11

The failure of the District Bank in 1857 involved the

whole family, and once again her patience, faith, and courage were needed to

help her husband through the worst of the crisis. Indeed, more than that may

have been required: in June 1859 Edward's private ledger records her lending him

£100 at interest. Though he gave her £20 cash in May 1861, she was still

receiving £5 p.a. on her loan in June 1867.12

The 1861 census found her living with her family and four servants at 1 South Ashfield Villa, Elswick Lane, Elswick, Newcastle. She continued to live at South Ashfield for the rest of her life. In November 1862 she donated a parcel or box of clothing and materials to the Relief Clothing Association. In 1863 she was on the committee for the girls' Ragged & Industrial School at Newcastle.13

It was a great trial to her that when Edward became ill and finally died in 1863, she was no longer able to see him and nurse him as she used to do. The loss of her husband was great, but she bore up, for her children's sake, with a brave spirit. In times of trouble she was always strong and never gave way to a selfish sorrow. In his will Edward had left the bulk of his estate in trust, from which Jane was to receive the income for her lifetime.14

In March and October 1865 she attended Monthly Meeting on behalf of Newcastle Women's Preparative Meeting. In June 1866 she was elected to the ladies' committee of the Girls' Royal Jubilee School, in Croft Street, Newcastle. She attended Yearly Meeting in 1867. But that year some financial troubles were such a bother to her, and her son George's health was so indifferent, that the whole family went to spend the summer at Lucerne, in Switzerland. She was photographed there, in July. In November that year she donated £10 to the collection for establishing workshops for the blind. In August 1868 she was one of two women appointed by Monthly Meeting to visit Lucy Fenwick Watson, on her application for membership.15

Her tendency to early blindness was by now being realized. As her sight failed, she was still able to write to her children by means of an instrument called the 'noctograph'. By December 1869 she was quite blind, but still enjoying her life very much, spending her evenings quietly, with her children reading to her. In January 1870 she subscribed £2 to the Sustentation Fund of the Prudhoe Memorial Convalescent Home; and in February £1 to the Newcastle-upon-Tyne General Soup Kitchen. The following month she had a cataract in the right eye surgically removed by Dr Bell Taylor of Nottingham, restoring the sight; but her left eye later had to be removed entirely; the operations were performed under chloroform.16

richardson2.jpg)

In October 1870 she subscribed £5 to the Society of Friends' War Victims Fund.16A

In 1871 she was living at South Ashfield, on the interest of her money, with an unmarried daughter, a cook, and two housemaids.17

She was an elder of her meeting, a faithful member of the Society of Friends, much attached to its principles, but very tolerant of those who differed from her in matters of belief. She was, in her general life, of a hopeful and gladsome spirit. It seemed as if it were given her to illustrate the principle of gladness, which she thought was sometimes wanting in the daily routine and in the public worship of even devoted Friends; even in her blindness, her powers of memory and imagination were such, that a stranger walking with her in the cherished scenery of Grasmere or Scotland would hardly realise that she could no longer see the objects of which she spoke so enthusiastically. She rejoiced in the marriages of her children and the advent of her grandchildren.18

In the summer of 1872 she visited Kreuznach with her daughters Allie and Nellie, but had to curtail her visit in view of the declining health of her daughter Anna, at Grasmere. In the autumn of the same year she had a serious illness herself, which caused much anxiety.19

In her final years her health declined. In November 1872 she had an attack of gastric flu; and in Spring 1873 she had more than one epileptic seizure, depriving her for the time of speech; after one attack she was unconscious for 40 hours. After this her memory was much confused. She made her will on the 3rd March 1873. She was ill for the whole of that year. After fluctuations of sickness, extreme weakness, and unconsciousness, on the 30th November she became paralysed, and she gently expired, at South Ashfield, after five days apoplexy, at about 1 o'clock on the morning of the 5th December. For the last two days the only sign of life had been her breathing. Her face, which during that year of illness had gained much dignity and sweetness, bore the impress of perfect peace, as if she might have said, "I have seen God's hand through a life time, and all was for the best." She was buried in Westgate Hill cemetery, Newcastle, on the following Monday, 8th December, beside her husband and the three children who had predeceased her. There was a gathering at South Ashfield, on the evening of the funeral, at which friends and family spoke very impressively, and "with much weeping bore testimony to the innate nobleness of her character".20

Her son John Wigham Richardson was the sole executor of her will, proved at Newcastle on the 11th April 1874, estate under £2000 (£91,400 at 2005 values), no leaseholds. After bequests of £100 to her cousin Eliza Wigham and £10 to her attendant Elizabeth Yorke, everything was to be equally divided between her children. Her son John later wrote of her: "My dear mother, to love her was a liberal education!" And her son-in-law Robert Spence Watson wrote of "the gentle Mother" that "we see that sweet unselfish smile which gladdened all our ill."21

Jane Wigham was the eldest child of [P2] John Wigham, and the only child of [P7] Ann Wigham.22

1 birth digest (Scotland)—entry appears to read 'Lothian St, Mid-Lothian); Scotland Non-Old Parish Registers Vital Records; Strath Maxwell; Annual Monitor 1875; The Scotsman, 1830-05-01; John Wigham Richardson: Memoir of Anna Deborah Richardson Newcastle 1877; JWR in Richardson (1877); Eliza Wigham in John William Steel: A Historical Sketch of the Society of Friends 'in Scorn called Quakers' in Newcastle & Gateshead 1653–1898. London & Newcastle, Headley Bros. 1899:161

2 TNA: RG 6/1149; Minutes of Newcastle Monthly Meeting, TWAS MF 169; Scotland Non-Old Parish Registers Vital Records; Anne Ogden Boyce: Records of a Quaker Family: The Richardsons of Cleveland. London: Samuel Harris 1889; marriage digest (Scotland); Eliza Wigham in Steel, op. cit.:161; Scottish Record Office SC70/4/82, pp. 479–543 and SC70/1/113, pp. 367–382; The British Friend; The Scotsman, 1830-05-01

3 William Harris Robinson, in Steel, op. cit.:70, 129; Sansbury, Ruth: Beyond the Blew Stone. 300 Years of Quakers in Newcastle. 1998: Newcastle-upon-Tyne Preparative Meeting; minutes of Friends' Sabbath School, Newcastle, TWAS MF 208; minutes of Newcastle Preparative Meeting (Women's) 1834–1878, TWAS MF 194; minutes of Newcastle Monthly Meeting, TWAS MF 169; Newcastle Courant, 1833-11-23

4 TNA: HO 107/824/10 f21 p34; RG 6/1149; daughter's birth certificate; Percy Corder: The Life of Robert Spence Watson. London: Headley, 1914

5 Dictionary of Quaker Biography; Eliza Wigham in Steel (1899):161

5A Newcastle Courant, 1845-03-07

6 Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson: 24

7 The British Friend; C. Peter Ripley, Introduction to The Black Abolitionist Papers, Vol. I: The British Isles, 1830–1865, 1985: University of North Carolina Press (also published at http://uncpress.unc.edu/chapters/ripley_black1.html); Newcastle Journal, 1848-11-04; Newcastle Journal, 1848-11-25; Nonconformist, 1849-07-04. The Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail of 1886-10-25 claims that the women who purchased the freedom of Frederick Douglas were "Mrs Edward Richardson and Mrs Anna Richardson, probably assisted by Mrs Robert Forster and Miss Ellen Richardson"; I have found no other evidence for Jane Richardson's direct involvement, the benefactors usually being named as Anna and Ellen Richardson, only.

8 HO 107/2404 f469 p57; Minutes of Newcastle Preparative Meeting (Women's) 1834–1878, TWAS MF 194; minutes of Newcastle Monthly Meeting, TWAS MF 169; Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury, 1850-01-05; Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury, 1851-05-17

9 Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson: 70, DQB; Mood, Jonathan, 'Women in the Quaker Community: The Richardson family of Newcastle, c. 1815–60, Quaker Studies 9/2 (2005): 213

10 Richardson (1877) :94; Minutes of Newcastle Preparative Meeting (Women's) 1834–1878, TWAS MF 194

11 Newcastle Journal, 1857-01-17

12 DQB; Richardson private ledger, TWAS Acc. 161/330

13 RG 9/3815 f47 p2; death certificate; Ward's 1865 Directory of Newcastle & Gateshead; Sansbury (1998); Newcastle Chronicle, 1862-11-29

14 DQB; Elizabeth Spence Watson: 'Family Chronicles'; husband's will

15 minutes of Newcastle Preparative Meeting (Women's) 1834–1878, TWAS MF 194; Richardson (1877); Elizabeth Spence Watson: 'Family Chronicles/Home Records', and supplement; minutes of Newcastle Monthly Meeting 1867–1874, TWAS MF 170; Newcastle Chronicle, 1866-06-16; Newcastle Journal, 1867-11-09

16 Annual Monitor 1875—which says the operation was in 1868; Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 1870-01-11; Newcastle Journal, 1870-02-14; Richardson (1877) :251-5; Dr Bell Taylor died in 1909, having built up a strong reputation as an antivivisectionist and antivaccinationist—Letters of Mary Pollard.

16A Newcastle Courant, 1870-10-21

17 RG 10/5076 f56 p43

18 Annual Monitor 1875; Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson:162

19 Elizabeth Spence Watson: 'Family Chronicles/Home Records', and supplement

20 Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson; Annual Monitor 1875; The Friend 14:22 1874; death certificate; Elizabeth Spence Watson: 'Family Chronicles/Home Records', and supplement; will and grant of probate; Grave HER number 13231, TWSitelines

21 National Probate Calendar; Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson: 235; poem in Wayside Gleanings; will and grant of probate

22 Annual Monitor 1875; DQB

*** For an exhaustive treatment of the lives of Edward and Jane Richardson, please see this pdf file (updated October 2024). ***

John Wigham was born on the 2nd September 1781, at Burnhouse in Haltwhistle. From his third year he grew up in Scotland.1

He

became a cotton manufacturer in Edinburgh, and is so described at his first

wedding, to

[P7] Ann White, on the 4th

June 1807, at Stockton. Ann and John had only one

child:

[P1] Jane (1808–1873), born at

Edinburgh. In December 1809 the Commissioners & Trustees for Manufacturers &c.

in Scotland awarded him the highest premium, of £20, for "the best two dozen

Shawls for Scarfs".2

He

became a cotton manufacturer in Edinburgh, and is so described at his first

wedding, to

[P7] Ann White, on the 4th

June 1807, at Stockton. Ann and John had only one

child:

[P1] Jane (1808–1873), born at

Edinburgh. In December 1809 the Commissioners & Trustees for Manufacturers &c.

in Scotland awarded him the highest premium, of £20, for "the best two dozen

Shawls for Scarfs".2

In 1811 and 1812 J. & J. Wigham, Manufacturers and Silkmen, had their premises at 6 Lothian Street, Edinburgh. By 1813 John had built a home for himself, at 10 Salisbury Road, Edinburgh; he lived the rest of his life there. A century later his grandson told a tale in this connection:

My grandfather once asked me how it was that, since Noah's Ark, men had been building ships and had not yet hit upon the right model.

"That may be so," I replied, "but have we not been building houses since Adam without arriving at a perfect dwelling?"

"I don't know about that," said he. "I built this house myself and I don't think it could be much improved upon."3

In 1813/14 John Wigham and Co., manufacturers, had their premises at 12 Lothian Street, Edinburgh. In 1823 he was described as a shawl-manufacturer, and in 1830 as "late" a silk manufacturer—for he had been able to retire early from business in easy circumstances owing to his first wife having inherited a considerable fortune. The Edinburgh shawl trade was almost entirely in the hands of Friends, among whom "the Wigham cousins, who set up a business in Nicolson Street about 1820, were outstanding." According to the Edinburgh Gazette the firm of J. & J. Wigham, Shawl-Manufacturers and Silkmen, was dissolved by mutual consent on the 20th July 1829, the business being continued by John Wigham's cousin and ex-partner John Wigham, Tertius.4

In late 1816 he acted as convener of a subcommittee for visiting and reporting on applicants for an employment project for relief of the labouring classes in Edinburgh. In July 1817 he was elected to the committee of management of the proprietors of the extension of the Union Canal from Edinburgh to Falkirk. In 1818 he was prominent among friends who promoted an inquiry into alleged abuses and irregularities in the Infirmary; the official report denied the more serious charges, but admitted some dislocation in consequence of an epidemic the previous year; several improvements were made. In September 1818 he met Joseph John Gurney, on a visit to Edinburgh. In May 1822 he subscribed £5 for Distressed Irish. For the year 1822/23 he was one of thirty general commissioners of police in Edinburgh, a position to which he had been first elected the previous year; he retired from this position in 1828. In January 1823 he attended a General Meeting of the Contributors to the Royal Infirmary. In October 1824 he became a member of a committee to raise a subscription for a house of refuge for male juvenile delinquents. In February 1825 he addressed a general meeting of the Equitable Buildings Company; and in July that year he subscribed £105 to the new Infirmary, and at the end of June 1826 £3 for the relief of unemployed operatives. In March 1827 he was Convener of the Eight Southern Districts, for a meeting to consider the Bill for altering and amending the Bridewell in Edinburgh. In 1828 he was one of the ordinary managers of the Eye Dispensary of Edinburgh.5

On the 18th June 1829 he was examined as a witness for the defence in a fraud trial in the Edinburgh Jury Court, relating to the supply of cashmere yarn; this was an area in which he had experience, as his firm imported cashmere yarn from France. The partnership between John Wigham, Jr, and his father, shawl manufacturers of Edinburgh, was dissolved on the 8th September 1829.6

He married, secondly, Sarah Nicholson (1803–1872), on the 21st May 1830, at Whitehaven, Cumberland; he was described as a silk manufacturer of Edinburgh. Sarah's own fortune—either brought with her at this time, or inherited later—amounted to £2000. Their children were: John Thomas (1832–1897), Sarah Elizabeth (1834–1854), Anna Mary (1836–1904), and James Anthony (1838–1885); all were born at 10 Salisbury Road, Edinburgh.7

In 1832 he published as a pamphlet his 'Letter to the Citizens of Edinburgh, on the expediency of establishing a house of refuge for juvenile offenders'. That year the 1832 electoral register for Tindale ward, Haltwhistle, showed John Wigham, Jr, of Edinburgh, as the proprietor of freehold houses and land at Burnhouse, in the occupation of Thomas Hymers; similarly that for Edinburgh showed him as late a shawl manufacturer, owner-occupier of 10 Salisbury Road (he had voted for Jeffery and Abercrombie).8

In February 1833 he chaired a public meeting of the southern districts association auxiliary to the Edinburgh Anti-Slavery Society, promoting the petition against slavery. In August 1834 he was present at a large-scale breakfast at the Waterloo Hotel, Edinburgh, celebrating its abolition; he seconded a resolution. In 1835 he was President of the Edinburgh Chamber of Commerce and Manufactures. He was a staunch Liberal in politics. In April 1838 he moved the vote of thanks at a public meeting, at which concerns were expressed at the manner of the implementation of the Emancipation Act. At the beginning of 1839 he spoke at a public meeting advocating repeal of the Corn Laws, and in June that year he chaired a public meeting at the Merchants' Hall, at which the decision was taken to found the Anti-Corn-Law Association, to the committee of which he was appointed (the formation of this association had been discussed as early as January 1834, at a meeting he had chaired). In early 1839 his Edinburgh speech on the abolition of the Corn Laws was widely reported. In 1839 he seconded, and in 1840 he nominated, Mr (later Lord) Macaulay as member for Edinburgh; and two years later became chairman of the Anti-Corn-Law Association. In January 1842 he chaired the meeting of the committee of the Anti-Corn-Law Association of Edinburgh, at the Chamber of Commerce, but was not, as expected, among the five delegates from there who attended the meeting in London in February. He later broke with Macaulay over the Anti-Corn-Law League; and after Macaulay's libels on Fox and Penn he destroyed all his letters from him. He was one of the leading advocates of Free-trade, down to the triumph of the cause in 1846.9

In November 1835 an unsigned article in The Age referred to John Wigham contemptuously, as part of the Edinburgh Whig Reform Clique, describing him as . . . "pious lank-haired Quaker Wigham, who throws up his eyes and turns white when he thinks on the Blacks" . . . .10

In January 1836 he seconded a resolution at the first annual meeting of the Scottish Prison Discipline Society, advocating an educational approach to the punishment of juvenile delinquents. In April 1837 he was a signatory to a letter advocating the abolition of the death penalty for all offences short of murder. In August 1839 he was appointed to the General Board of Directors of Prisons in Scotland. He was one of the Royal Commissioners on Prisons for Scotland, and long took an active interest in that department. As a philanthropic measure, he had long advocated the establishment of reformatories for juvenile criminals on the system he had the satisfaction of seeing at length almost universally adopted.11

In August 1839 he addressed an open letter to the rate-payers of St Cuthbert's parish, urging attendance at a public meeting to look at fairer and better provision for the poor in Scotland; he had been one of 120 Managers appointed to conduct the affairs of the poor during the previous six years. Later that month he took up the cause of the poor of the West Church parish, seeking to get the claims of widows with families placed on a better footing. He resigned his office as a Manager of the Poor and, having been offered the gratuitous legal assistance, resolved to try, in the Court of Session, the first case that came to his knowledge in which the claims of widows were not properly attended to. In April 1840, at a meeting at the Institution Rooms, Queen Street, he was among those elected to the committee of a new Association for Inquiring into the Pauperism of Scotland. In January 1842, at a meeting of the Scottish Board for Bible Circulation, he was appointed to an interdenominational committee to oversee the implementation of its resolutions, namely the dissemination of cheap bibles.12

In April 1836 he was appointed a director of the Forth Steam Navigation Company, at its inaugural meeting. In September 1838 he was on the platform at a public meeting of the Aborigines Protection Society, at a church in Rose Street, for the purpose of hearing about the condition of the native population of British India. In January 1840 he was delegate from Edinburgh to the Operative Anti-Corn-Law Association. The 1840–1 Edinburgh directory describes him as a gentleman. The 1841 census recorded him as of independent means, with his wife, four children, and two servants, at Blawlowan, Logie, Stirlingshire. Early in the following year he chaired an Anti-Corn-Law Conference in Edinburgh, at which he said:

Gentlemen, I have, from the year 1815, when the first of these Corn-laws were passed, felt that they were oppressing the poor [ . . . ] Every year has witnessed increased oppression from these laws, and matters appear to be drawing to a crisis—all parties begin to feel that something must be done—even the robbers (of which I am one to a small extent) seem to be alarmed, probably under the idea that if they do not change their course, the time will come when there will be few persons left to eat their taxed food. Gentlemen, it appears to me that these laws are nothing short of legalised robbery, they are consequently immoral and sinful (applause).

In 1843, described as of Salisbury Road, Edinburgh, he acted as executor of the will of his sister Jane (Wigham) Cruickshank. In February and March of this year he was noted as agent and correspondent for The British Friend. On the 11th January 1844 he was one of four men appointed to collect subscriptions in Edinburgh and neighbourhood, for a Great League Fund of £100,000; a special fruit soirée was be held in the new music hall that day, to receive a deputation from the National Anti-Corn-Law League, including both Richard Cobden and John Bright; he had corresponded with Cobden at least as early as 1841. In April he chaired a meeting of the Anti-Corn-Law Association at the Chamber of Commerce, and was re-elected as Chairman of the Association (he was Chairman again in 1845, and in January 1846 subscribed £50 to the Anti-Corn-Law League; the Association's objectives having been achieved, the Association was dissolved in January 1847). That month it was recorded that he had contributed £1-1-0 to the annual subscription for the Royal Infirmary. In July he was elected as a Director of the Chamber of Commerce. By February 1846 he was one of two Trustees of the Edinburgh Property Investment Company, which was essentially a building society; he continued as a Trustee until at least 1861, by which time their numbers had increased to four. The Company was a success, and in 1849 he was one of three Trustees of the Second Edinburgh Property Investment Company; in 1853 he was one of four founding Trustees of the Improved Edinburgh Property Investment Company. The Edinburgh Property Investment Company was Scotland's first ever building society, and is still in operation, now as the Scottish Building Society, which claims to be the oldest remaining building society in the world.13

In June 1843 he was one of seven vice-presidents of the General Anti-Slavery Convention, in London.14

In the summer of 1846 he holidayed with the Richardsons by the seaside, at the village of Dirleton, not far from the Bass Rock. For a number of years he rented a cottage, called Morton Cottage, at Langnieldry, close to the sea, near Prestonpans and Musselburgh.15

On 15 January 1847, 27 March and 23 May 1848, and 28 May 1849 he was one of five signatories to a declaration and order of the General Board of Directors of Prisons in Scotland, on the opening of the new prisons at Stornoway, Lochmaddy, Stranraer, and Inverness, respectively. He was similarly a signatory to the declarations and orders regarding the discontinuance of the prisons at Port-Glasgow and Leith, on 14 February and 15 September 1848 respectively. In January 1848 he chaired a public meeting in Edinburgh to promote the abolition of capital punishment. On the 23rd April 1849 he signed the declaration and order introducing new regulations for the general prison at Perth, and on the 10th May 1850 regarding the use of the prison at Greenock.16

In February 1847 he subscribed £2.0.0 to the Cobden National Tribute Fund. In February 1848 he was a committee member of the Scottish Patriotic Society.17

In April 1848 he was Convener of the Committee for the Relief of Unemployed Labourers and Workmen of Edinburgh. John Wigham Richardson relates an incident of this period:

Our Grandfather, though one of the mildest of men, had a habit of occasionally, very occasionally, expressing himself rather strongly. During the Irish famine he had to distribute some Government relief, and was applied to, by a young man, for assistance. He was told that no relief could be given to able-bodied unmarried men. The next morning, the youth applied again, and stated that, after what he had been told the day before, he had got married forthwith. I well recollect my good Grandfather bursting out with—"Thou rascal, thou scoundrel, get out of my library!"18

His library, incidentally, was an excellent one.19

In December 1848, with William Miller, he wrote the recommendatory preface to the English edition of Christian Non-Resistance, in all its important bearings, illustrated and defended by Adin Ballou. Just after Christmas he was on the platform of a public meeting of the Financial Reform Association, at the Waterloo Rooms. In this year his wife Sarah was president of the Edinburgh Female Emancipation Society, which drew up an 'address to their Sisters in Paris.' 20

He first interested other gentlemen in George Parker Bidder, the 'calculating boy', and subscribed himself for his education.21

In April 1849 he was a member of a deputation to the Town Council, urging a reduction in the number of public houses within their jurisdiction; this was a lasting concern, and in April 1857 he was a member of a deputation to the magistrates, proposing a reduction in the number of licences. In August 1850 he was one of six men appointed as delegates to the Peace Congress to be held in Frankfurt that month. In January 1851 he was a signatory to a request to the Lord Provost of Edinburgh to convene a public meeting on the positive implications of the recent treaties with Spain and Brazil for the promotion of the extinction of slavery. In March he was on the platform of, and moved the motion at, a public meeting of the Edinburgh Financial Reform Association held at Queen Street Hall, to petition Parliament to look at ways of effectively implementing the new treaties. In the census that year he was described as late a merchant; his household at that date included a cook, a house maid, and a gardener—for 10 Salisbury Road had a charming, if formal, garden at the back. He was a director of the United Kingdom Provident Institution. "Devoted to benevolent and useful institutions," he served on the boards of the Edinburgh House of Refuge and the Royal Maternity Hospital, and was one of five members of the General Board of Directors of Prisons in Scotland. In 1851 he proposed 'schools for the destitute', at which juvenile offenders would be trained for farming at home or in the colonies. He published a pamphlet 'To John Shank More, Professor of the Law of Scotland in Edinburgh University' on the 10th July that year, presenting his views on juvenile delinquency, based on his experience as a member of the Board of Commissioners for Prisoners from 1839 to 1850.22

In 1851 a number of shawl manufacturers were represented at the Great Exhibition. Among these, "The tartans of Messrs. John Wigham and Sons, of Edinburgh, are also very superior": the official catalogue lists "WIGHAM & SON, Edinburgh, Manu.—Tartan plaids, or long shawls, of various Highland clans, combined or separate".23

In June 1852 he sat on the platform of a meeting of the Lord Provost with the electors of the city; he was said to have been "intimately acquainted with the Lord Provost since the commencement of the Corn-Law agitation." In October a letter from him regarding the treatment of juvenile delinquents was read to the town council. That year too a letter by John Wigham of Edinburgh was read to the Conference of the Friends of Peace, and the following year he was a signatory to the circular letters of invitation to the January Arbitration and Peace Conference in Manchester and the October Edinburgh Peace Conference.24

In January 1853 John Wigham, of Salisbury Road, Newington, Edinburgh, signed a trust disposition and settlement—essentially a will. In it he made provision for his wife, and for all his children except Jane, for whom he had already provided. He had to make very specific provision for his youngest son, James Anthony, who "had severe convulsion fits which deprived him of speech and seriously impeared his mental powers so that it has been necessary for him to have a male attendant constantly". An 1854 codicil describes John Wigham's real estate in considerable detail: he still had a shop and a house in Lothian Street, as well as three other properties in Edinburgh. By 1855, however, he had given up Morton Cottage. In an 1856 codicil he bequeathed his horse and carriage to his wife. In 1857 he was an executor of his brother Anthony's will.25

In February 1853 he was listed as a shareholder in the Manchester and Liverpool District Banking Company. In August 1853 he was part of a deputation from the Chamber of Commerce that met with Lord Corriehill regarding the Government Commission on the Mercantile Laws. In November that year he wrote a testimonial for John Brown, an escaped slave, later published in Slave Life in Georgia. A Narrative of the life, sufferings, and escape of John Brown, a fugitive slave, now in England, 1855. In October 1856 Harriet Beecher Stowe and party stayed a week with him. His granddaughter Anna Deborah Richardson recorded with some amusement how John Wigham denounced their antiquarian tastes:

. . . "musty old places,

smelling of blood, it is mere infatuation to care for them. I like something

useful, and see no good in the castles, and bungling walls. We ought to be

thankful we live in better times, and know how to live at peace like sensible

citizens," &c., &c.26

In June 1854 he was one of four vice-presidents of the newly formed Edinburgh Anti-Slavery Society. In 1854/55 he was a member of the Board for Scotland of the United Kingdom Temperance and General Provident Institution.27

In 1856 he acted as executor of the will of his brother-in-law John Barlow, and in 1857 co-executor of that of his brother Anthony.28

He was a lover of cream, and of country fare.29

In October 1857 he attended the Two Months Meeting in Edinburgh, and was able to distribute there a dozen copies of the Report of the Retreat.29A

In 1858 the failure of the Western Bank of Scotland brought him to poverty—although it would appear not to destitution, for it is recorded that he was obliged to give up his carriage, implying little further hardship.30

Anna used to tell an anecdote about the subscriptions of her Grandfather to charitable objects. One day a gentleman called to tell him how a certain society was getting on, and concluded by saying: "Now, do not think, Mr. Wigham, that I am going to tease you about your subscription. I know that circumstances with you are changed." The good old man turned away his face, and then looking up, with a tear in his eye, he said: "No! I will give thee my mite. It is only the pride of the old Adam which makes John Wigham shrink from seeing five shillings opposite his name, where there used to stand twenty pounds!" In 1859 he subscribed 10s. to the Royal Infirmary.31 From October 1858 Anna Deborah Richardson kept house for him in Edinburgh. Her descriptions of her grandfather portray him clearly:

Grandpapa looks weak, and sadly shrunk. He is very kind and gentle; only once, in the midst of a general talk, he glanced at my dress, and with averted face, his aged cheeks quite flushed, said: "If I were a woman of sense, sooner than follow those ridiculous fashions, I'd be hanged!" Grandpapa is a thorough gentleman, polite to all sorts and conditions of men and women, and there is a mild dignity in his manner curiously contradicted by the half curses on people and things, which burst forth every now and then. Dear man, he still stumbles away over the names in the Acts, as I have heard him do all my life. He is much feebler than he was two years ago, and cannot bear labour of any kind.32

It was said that his mind was "a very finely moulded one, by nature, and he takes generous views of every fresh subject presented to it."33

In 1860 he was a subscriber to a prodisestablishment society.34

The 1861 census described John Wigham as a retired shawl manufacturer, now fund holder and proprietor of houses, of 10 Salisbury Road, St Cuthbert's, Edinburgh, living with his wife, two children, and three servants (including an attendant for his son). In an 1861 codicil to his trust deed he bequeathed his "Watch and appendages along with my body clothing and whole other Contents of my Wardrobe" to his wife.35

The Edinburgh Daily Review described him as "one of the most estimable of our citizens." It continued:

He has, through the course of his long life, been identified with every movement having for its object the welfare of the people. In his earlier years he was a faithful visitor for the Destitute Sick Society, which naturally led him to investigate the affairs of the Royal Infirmary; and some will remember the energy and zeal with which he exposed the then existing abuse of that institution. He also, while connected with its management, placed the affairs of the West Kirk workhouse on such a basis as to ensure an administration of strict economy coupled with wise liberality. In the abolition of slavery and the promotion of peace he took a hearty and continuous interest. He was one of the earliest to see the important political and philanthropic bearing of the abolition of the corn laws, and, we believe, made the first motion on the subject submitted to a British audience; it was proposed in the Chamber of Commerce, of which he was then Chairman.36

He was an elder, possessed of a superior understanding and good judgement, deeply founded on his religious beliefs, and was well qualified to be a guide to others. He was always ready to listen and to help with his advice and counsel not only the poor, but anyone who applied to him, and he treated them all with a disinterested and unselfish judgement and goodness of heart. In spite of his many qualities he was a truly humble man; he was at all times backward in speaking of himself and his attainments and felt that any good he had been able to accomplish was the will of God. For the last three years of his life he was often in great pain, which he endured with patient resignation, though it meant that he was unable to take any share in public affairs.37

Described as formerly a shawl manufacturer, he died at 3pm on Tuesday the 29th April 1862, at his home, from decay of nature. An Elder of his meeting, the Daily Review obituary concluded: "In the death of Mr Wigham, the Society of Friends has lost one of its brightest ornaments, and this city one of its greatest and most enlightened benefactors." His body was interred at the Friends' Pleasance burial ground in Edinburgh on the 5th May.38

A detailed inventory of his estate was made, of which what follows is a simplified version39:

I |

Personal Property in Scotland |

£ |

s |

d |

1 |

Cash in the house |

10 |

– |

– |

2 |

Household furniture Silver plate bed and table linen and other Effects in the house |

260 | 10 | 6 |

3 |

Balance on an account current with the British Linen Company, plus interest |

270 |

13 |

8 |

4 |

Consolidated Stock in the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway made over to the deceased in lieu of five shares of stock held by him in the Union Canal Company |

22 |

10 |

– |

5-7 |

Shares in the stock of the Arbroath Gas Light Company |

720 |

12 |

– |

8 |

Shares in the Brechin Gas Light Company |

222 |

10 |

– |

9 |

Rents of heritage due by the following parties falling under executry vizt 1. Rent received from Messrs M. & A. Dickson for shop and premises in Lothian Street Edinburgh for half year 2. Rent of dwelling house in Court No 6 Lothian Street Edinburgh received from Mr William Hunter tenant thereof for half year |

17 |

12 |

3 |

10 |

Feus falling under executry received from the following parties viz 1. Feu received from Mr Torrance for subjects in Bristo Street Edinburgh for year 2. Feu duty by Mr Macqueen for subjects in Bristo Street Edinburgh for year |

14 |

15 |

2 |

11 |

Proportion of Annuity of £10.14/– per annum payable half yearly due by the Standard Life Assurance Company to the deceased at his death |

4 |

16 |

8 |

12 |

Proportion of Annuity of £10 per annum due to the deceased by Walter Wilson Esq. Hawick payable yearly |

9 |

14 |

10 |

13 |

Sum due by Mrs Lunn Parkside Street Edinburgh to the deceased being money lent by him to her at various times per Pass Book. From the debtor's circumstances the debt is considered desperate, so reduced to 1/– in the pound |

|

2 |

4 |

14 |

Shares of the Western Bank of Scotland Glasgow, the Bank being insolvent |

24 |

– |

– |

|

Dividends due on items 5-7 |

22 |

10 |

– |

|

Amount of Personal Estate situated in Scotland |

£1560 |

7 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

II |

Personal estate situated in England |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

Stock in the London and South Western Railway |

2160 |

– |

– |

16 |

Shares in the New South Western Steam Navigation Company Southampton |

675 |

– |

– |

17-8 |

Shares in the Warrington Gas Light and Coke Company |

2318 |

– |

– |

19 |

Dividend due on Warrington Gas Light & Coke Co. |

59 |

7 |

8 |

20-1 |

Shares in the North and South Shields Ferry Company |

1365 |

– |

– |

22 |

Dividend due on N. & S. Shields Ferry Co. |

48 |

13 |

– |

23 |

Sum lent to Mr Henry Nicolson Draper Chelmsford, plus interest |

100 |

6 |

8 |

24 |

Sum lent to Messrs J.D. Carr & Co. Carlisle, plus interest |

447 |

9 |

10 |

25 |

Sum lent and advanced at various times to his son John Thomas Wigham Newcastle on Tyne to put him in business there, plus interest |

2078 |

15 |

4 |

26 |

Sum due from John Thomas Wigham as rent of business premises occupied by him in Newcastle upon Tyne, 1854–1862. This debt from the circumstance of the debtor is considered bad and not worth more than 5/– in the pound or |

765 |

14 |

11 |

|

Amount of Personal Estate situated in England |

£7939 |

14 |

1 |

|

Amount of Estate at date of Declaration |

£9500 |

1 |

6 |

|

(£410,063 at 2005 values) |

||||

At the end of December 1862 his former home was put on the market:40

|

TO BE SOLD OR LET, No. 10 SALISBURY ROAD, NEWINGTON. THE HOUSE AND GROUND, No. 10 SALISBURY ROAD, NEWINGTON, recently occupied by the late John Wigham, jun. The House is large and convenient, well suited for the accommodation of a Gentleman's Family. It is situated in the best part of Salisbury Road, commanding an extensive view of Liberton and the Lammermoor Hills. The House contains Drawing-Room, Dining-Room, and Small Library, Seven Bed-Rooms, Bath-Room, Store-Room, Kitchen, Wash-house, Laundry, and all the other conveniences usual in a Gentleman's Residence; a Beautiful Flower Garden and Greenhouse; a Two-Stalled Stable, Coach-house, &c., and accommodation attached for a Man Servant. Annual Feu-duty only 5s. |

John Wigham was the sixth child and third son of [P3] John and [P4] Elizabeth Wigham.41

1 TNA: RG 6/304; Dictionary of Quaker Biography—including entry for his father [P3] John Wigham

2 RG 6/203, /527; DQB; Strath Maxwell

3 Caledonian Mercury, 1809-12-14; letter to me from National Library of Scotland; Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson: 19; Post Office Directory Edinburgh, 1850–1; Post Office Directory Edinburgh & Leith; death certificate

4 Post Office Directory Edinburgh; L.C. Coombes: 'Wigham of Coanwood.' Overprint from Archaeologia Aeliana, 4th ser. vol. xliv, 1966; DQB; William H. Marwick (1954) 'Friends in Nineteenth Century Scotland' , JFHS 46.1:9, Spring; Edinburgh Gazette 1829-09-04

5 The Scots Magazine, 1817-01-01; The Scots Magazine, 1817-08-01; "A.B." Rambling Recollections (1867), p. 67; Logan Turner: Story of a Great Hospital, pp. 200–1, cited in Marwick (1954) :10; Memoirs of Joseph John Gurney with Selections from His Journal and Correspondence Part 1: 154; The Scotsman, 1821-07-14; Caledonian Mercury, 1822-05-20; Caledonian Mercury, 1822-07-01; The Scotsman, 1823-01-08; Caledonian Mercury, 1824-10-25; Caledonian Mercury, 1825-02-10; Caledonian Mercury, 1825-07-28; Caledonian Mercury, 1826-07-01; The Scotsman, 1827-03-14; The Scotsman, 1827-03-17; Caledonian Mercury, 1828-05-24; The Edinburgh Almanack, 1828

6 Morning Chronicle, 1829-06-25; Morning Chronicle, 1829-09-09

7 RG 6/1155; Strath Maxwell; DQB; Scottish Record Office SC70/4/82, pp. 479-543 and SC70/1/113, pp. 367-382

8 National Library of Australia, catalogue entry; electoral registers

9 Perthshire Advertiser, 1834-02-06; The Scotsman 1833-02-02, 1834-08-02, 1838-04-25, 1839-01-23, 1839-07-31, 1842-01-29, 1842-02-02, 1862-04-30; John O'Groat Journal, 1839-02-08; Inverness Courier, 1839-06-12; Edinburgh Chamber of Commerce & Manufactures. Founded in the Year 1785. Incorporated by Royal Charter in the Year 1786. 160th Anniversary 1785–1945 (commemorative book); Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson; Obituary of John Wigham

10 'The Selkirkshire Fagots' , in The Age, 1835-11-01, p. 351

11 The Scotsman 1836-01-30; obituary of John Wigham, The Scotsman 1862-04-30; Sun (London), 1837-04-29; London Standard, 1839-09-04; The London Gazette, 1839-09-03

12 The Scotsman 1839-08-03, 1839-08-24, 1840-04-11, 1842-02-12

13 The Scotsman 1836-04-16, 1842-01-12, 1844-01-06, 1844-04-13, 1844-07-10, 1844-02-15, 1846-02-04, 1848-01-29, 1849-01-17, 1849-03-10, 1853-12-07, 1853-12-24, 1861-12-23; Caledonian Mercury, 1838-09-06; Greenock Advertiser, 1846-01-20; Edinburgh & Leith Post Office Directory; information from Karen Yeoman; The British Friend; 1841 Scotland census; www.scottishbldgsoc.co.uk/view_company_info.asp?fld_company_info_id=19; The Guardian 1840-01-15; Leicester Journal, 1847-01-22; catalogue entry for his letter to Richard Cobden, West Sussex Record Office COBDEN/1. This is likely to be Blawlowan.

14 The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Reporter: Under the Sanction of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society 12:89, 1843-06-14

15 Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson: 18; John Wigham Richardson: Memoir of Anna Deborah Richardson Newcastle 1877:5; TS Reminiscences of Elizabeth Spence Watson; Scottish Record Office SC70/4/82, pp. 479-543 and SC70/1/113, pp. 367-382

16 Edinburgh Gazette; Dumfries and Galloway Standard, 1848-01-19

17 The Guardian 1847-02-06; Caledonian Mercury, 1848-02-10

18 The Scotsman 1848-04-04; JWR in Richardson (1877):122; Caledonian Mercury, 1848-05-18

19 Richardson (1877):1

20 Joseph Smith: Descriptive catalogue of Friends' books, vol. 2; British Friend, 7th mo. 1848, cited in William H. Marwick (1954) 'Friends in Nineteenth Century Scotland', JFHS 46.1:12, Spring; The Scotsman 1848-12-30

21 Richardson (1877) :176

22 1851 Scotland census; Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson:18-9; Marwick (1954) :15; The Scotsman 1848-09-20, 1849-04-25, 1851-01-10, 1851-03-03, 1857-04-29, 1863-04-21; Edinburgh News and Literary Chronicle, 1850-08-03; The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison, Vol. IV: From Disunionism to the Brink of War, ed. Louis Ruchames

23 Morning Chronicle, 1851-10-07

24 The British Friend X.4:77 and XI.10:254-5; The Scotsman 1852-06-17, 1852-10-06; The Guardian 1853-01-14

25 Scottish Record Office SC70/4/82, pp. 479-543 and SC70/1/113, pp. 367-382; will of Anthony Wigham, PCC

26 Staffordshire Advertiser, 1853-02-26; The Scotsman 1853-08-31; http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/jbrown/jbrown.html; Richardson (1877):97 & 100, ADR in Richardson (1877):98

27 The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Reporter: Under the Sanction of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, 11:249, 1854-11-01; Scottish Post Office Directory, 1854/5

28 Warwick and Macdonald: John Barlow; TNA: PROB 11//2261 copy will

29 Richardson (1877):178

29A Letter from John Wigham Jr to Wm Wood, 1857-10-10, The Retreat Archive, RET/1/5/1/54/11/38, Correspondence

30 Memoirs of John Wigham Richardson; Richardson (1877):152

31 Richardson (1877):176; The Scotsman 1859-08-15

32 Richardson (1877):121, ADR in Richardson (1877):122 & 125

33 Richardson (1877):160

34 Richardson (1877):173

35 1861 Scotland census; Scottish Record Office SC70/4/82, pp. 479-543 and SC70/1/113, pp. 367-382

36 Daily Review (Edinburgh) obituary

37 DQB; obituary of John Wigham, The Scotsman 30.4.1862; 1863 Annual Monitor

38 death certificate; Daily Review (Edinburgh) obituary; Strath Maxwell; 1863 Annual Monitor; The British Friend 1862-06-04 pp. 153–4; The Scotsman, 1862-04-30; Scottish Press, 1862-04-30; Edinburgh News and Literary Chronicle, 1862-05-03; gravestone; North Briton, 1862-05-03; Newcastle Chronicle, 1862-05-10

39 Scottish Record Office SC70/4/82, pp. 479-543 and SC70/1/113, pp. 367-382

40 Edinburgh Evening Courant, 1862-12-30

41 RG 6/304, /940; Annual Monitor; information from, and photocopied extracts from Strath Maxwell sent me by, Karen Yeoman

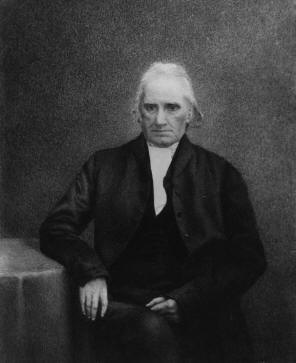

The second portrait of John Wigham is reproduced by permission of Friends House Library.

John Wigham was born on the 22nd April 1749, at Hargill House, Cornwood, near Haltwhistle, Northumberland. Religious feeling first stirred in him at the age of eight. He wrote that, as a boy, he was "frequently employed in taking care of sheep, all alone; and when so situated, my mind was often drawn to seek the Lord . . .".1

At the age of sixteen he was put to work with his father's servants and their company considerably unsettled him. He began to enjoy their merriment and folly and although he knew they were a danger to his spiritual life he was unable to free himself from them. His father thought that a good marriage would reclaim him and encouraged him to seek a wife.2

In 1769 he went to live with his grandfather [M15] Cuthbert Wigham; about this time he married [P4] Elizabeth Donwiddy. His marriage was indeed the means of separating him from his undesirable companions. He was favoured soon after his marriage with a fresh insight into the love of God and was brought to a sincere repentance for his folly and wickedness. The couple lived in Coanwood till 1784, having seven children there. Their children were: Jane (1770–1842, b. Woodhouse, Lambly, Northumberland), Rachel (1772 – before 1835), Amos (1774–1847), Anthony (1776–1857), Elizabeth (1779–1854), [P2] John (1781–1862), William (1783 – after 1841) (all born at Bournhouse in Coanwood), Hannah (1788–1846) and James (1790–1803).3

He appeared in the ministry when he was about 24. In the exercise of his gift he was careful to keep close to his divine leadings and was engaged at different times to visit many of the meetings around England. As a minister he was well regarded, being sound in faith and doctrine, living a life of self-denial and being truly "an example to the believer, in word, in conversation, in charity, in faith, in purity".4

Some time before 1783 he was impressed with the belief that God called him to leave his native country and go to live in Scotland. This was a sore trial to him and it was some time before he could accept that it was a divine requiring. In April 1784 the family moved to Edinburgh. As John wrote to Anne Read on the 12th:

. . . we purpose setting out, if all well, about the 25th of this instant, and I hope myself and daughter, that I intend to ride behind me, will get to Edinburgh on the 27th. My wife and servant, and four children will go in the diligence from Carlisle . . . I am just now returned from taking two children to school at Ackworth.

They took over a small dairy farm, Cockmalanie, about two miles from meeting. In 1786, also under the impression of religious duty, they moved to Aberdeen, running a small grocery store. In 1788 they took a farm in Kinmuck, 14 miles north of Aberdeen.5

He and his wife found the state of the Society in Scotland very discouraging. Monthly meetings continued to be held, but the right exercise of the discipline was insufficiently supported and it was not known who the members of the Society were. John and his wife caused proper lists to be drawn up and did much to put the Society on a surer footing and build up its influence in Scotland.6

In 1789 he visited Friends in Cumberland.

This visit, of which he has not left any account, was performed chiefly, it is believed, on foot; as were also many of his journeys to attend the Half-year's Meeting, in travelling to and from Edinburgh. He had been heard to say, that he and his companions when on some of these journeys, after walking as far as they were well able, were refused lodgings at some of the Inns, partly from their not appearing like profitable guests, and also on some occasions from the remains of a prejudice against Friends, which many in that day still entertained. The distance from Kinmuck to Edinburgh is upwards of 120 miles.7

![]()

In 1794 he visited Friends in America, travelling among them for three years, in both US and British settlements (including Nantucket and Nova Scotia). In the USA he visited the eastern seaboard from Nova Scotia to South Carolina. In the southern states, which he described as "a land of darkness", he "gave offence by his declaration of the universality of the love of God for coloured as well as white." He covered 22,752 miles in all. On the return crossing his ship was attacked by French privateers, but though other passengers had articles taken as plunder the prize-master did no more than lift the lid of John Wigham's chest. After his return home in 1797 he continued his journeys in Great Britain, and in the years 1798, 1799 and 1800 he was much from home, visiting many of the counties of England as far afield as Land's End in Cornwall, and going to South Wales and Guernsey; in 1798 and 1800 he attended Yearly Meeting in London, as one of the representatives from the Half Year's Meeting for North Britain. In 1806 he visited friends in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. During this period he lived when at home occasionally at Kinmuck, but was principally in Edinburgh (of which town he was a resident in 1799, and said to be a yeoman in June 1807) until in July 1807 he went to live permanently in Aberdeen. In 1806 he acted as executor of the will of his son-in-law John Cruickshank. After his removal he set off on his travels again, visiting Friends in and about London—he was in Sussex and Kent in 1809, attending Yearly Meeting again, in that year. In 1812 and 1813 he paid visits to Friends in Ireland, Cumberland and some parts of Lancashire and Westmorland, which he completed with considerable bodily suffering, and which proved the last of his engagements out of Scotland.8

Elizabeth Fry, who was a friend of his, described him in 1808 as "a nice old man in the lower line of life." She visited John and Elizabeth again in 1818, describing them as "our beloved old friends".9

He published An Address to Children in 1814, and in 1815 Christian Instruction: In a Discourse Between a Mother and Her Daughter.10

In May 1814 he attended Yearly Meeting in London, where he dined with Richard Cockin and others at Plow Court. He attended Half-Year's Meeting at Aberdeen in 1820. In July 1822 he was visited by William Allen, who noted "I was comforted in seeing the old veteran. His day's work is nearly done."11

He felt the loss of his wife in 1827 very deeply. In this year he wrote a note to his daughter Hannah, giving her all his household furniture, so long as he retained the use during his lifetime—this was to prove the nearest thing to a will he ever wrote.12

In 1828 he lived at Broadford, north-west of George-street, Aberdeen; in 1830 at "Bradford" in Aberdeenshire.13

He was a minister for about 67 years, and to the end took a lively interest in the membership and prosperity of the Society, even though his own health was failing and he was confined to his house for long periods; his mental powers were unimpaired. For several years the meetings of ministers and elders were held in his house.14

By 1828

. . . his eye-sight had become very defective, and soon afterwards it totally failed, so that writing became impracticable. His lameness also was such, that with difficulty he could move about, requiring even a painful exertion, to get occasionally into his garden; but during the long period of his confinement to the house, he was, under all his privations, and the pressure of many painful ailments, full of a contented resignation, often saying he had much cause for gratitude and thankfulness, for the many blessings and favours he still enjoyed. He was usually very open and cheerful, which rendered his company attractive to his friends, and he seemed to enjoy their visits . . .

For a number of years he seemed to live in a state of constant waiting for the call of his Divine Master to put off his earthly tabernacle . . . He sometimes said, he was tried with low times, and that the enemy was even permitted to buffet him; yet through all he was favoured with a hope, which never forsook him, that when the end came, all would be well . . .15

In January 1830, and again in January 1831, he donated 10s. to the Sick Man's Friend Society. In March 1838 he subscribed 10s. to the public soup kitchen of Aberdeen.16

William Allen met with him again in December 1832, noting of an interview he found "exceedingly interesting" that "Its occurrence was occasion of deep gratitude; and truly comfortable was it to witness the precious savor of heavenly good that appears to rest upon him, and to season both his company and conversation." In August 1838 Elizabeth Fry visited him again. Of this visit it was recorded that

He had been to her as 'a nursing father' in the early part of her religious course. It was much like the meeting and interchange of parent and child, after long separation and many vicissitudes; and these last, as they had affected our dear friend in the interval, were freely spoken of by her, with that deep feeling, chastened into resignation, which so remarkably covers her subjected spirit, in relation to these affecting topics.17

For several years he was quite blind, which he felt to be a great privation. For about three weeks before his death, he suffered much pain and sickness. John Wigham of Broadford, Aberdeen, described as "late shawl manufacturer", died early in the morning of the 17th April 1839, with very little struggle. He was buried in the Friends' burial ground at Kinmuck, on the 20th.18

An inventory was taken of his effects. His whole worldly wealth amounted to £74/11/8 (£3308 at 2005 values), made up of household furniture (£26/10/9), body clothes, books and an old watch (£3/12/6), half a year's rent on apartments in a house at Broadford (£2), and cash in the house, including the contents of an indorsed Bank deposit receipt (£42/8/5).18

The Annual Monitor described him as "a diligent and faithful labourer in the Lord's vineyard."20

In 1842 were published the Memoirs of the Life, Gospel Labours, and Religious Experiences of John Wigham.21

John Wigham was the second child, and first son, of [M18] William and [M31] Rachel Wigham.22

1 TNA: RG 6/1271; John Wigham: Memoirs of the Life, Gospel Labours, and Religious Experiences of John Wigham. London: Harvey & Darton, 1842; Dictionary of Quaker Biography

2 DQB

3 DQB; George Richardson: Some Account of the Rise of the Society of Friends in Cornwood in Northumberland, especially in connexion with the family of Cuthbert Wigham. London: Charles Gilpin 1848; David Sands: Journal of the Life and Gospel Labours. London: Charles Gilpin, 1848; Strath Maxwell; The Large and Small Notebooks of Joseph Wood

4 DQB

5 DQB; L.C. Coombes: 'Wigham of Coanwood.' Overprint from Archaeologia Aeliana, 4th ser. vol. xliv, 1966

6 DQB

7 Wigham (1842), p. 14

8 DQB; Sands (1848); Strath Maxwell; information from Karen Yeoman; RG 6/203; Coombes, op. cit; Wigham (1842), pp. 82, 89, 94 & 99; Martha Routh diary, download from Earlham College Library website

9-10 DQB; Fry diary entry, downloaded from Earlham College Library website; Jon Mitchell, in his essay 'Three Methods of Worship in Eighteenth-Century Quakerism' (in Robynne Rogers Healey, ed., 2021, Quakers in the Atlantic World, 1690–1830, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press), quotes from John Wigham's Christian Instruction, using it to exemplify silent waiting, as one of the three methods he distinguishes.

11 Nathan Hunt letters, and William Allen material, both downloaded from Earlham College Library website; Norman Penney, ed. (1929 & 1930) Pen Pictures of London Yearly Meeting 1789–1833; London: Friends Historical Society: 139

12 DQB; Scottish Record Office SC1/27/16 pp. 832-833 and SC1/36/16m pp, 1303-1308

13 RG 6/1155; Chalmers' Directory of Aberdeen 1828–9; Post Office Directory 1828–9

14 DQB

15 Wigham (1842), pp. 127-28

16 Aberdeen Journal, 1830-01-13, 1831-02-23, 1838-03-07

17 William Allen and Elizabeth Fry material, both downloaded from Earlham College Library website

18 Annual Monitor 1840; Wigham (1842); death/burial digest (Scotland), SRO SC1/27/16 pp. 832-833 and SC1/36/16m pp. 1303-1308

19 SRO SC1/27/16 pp. 832-833 and SC1/36/16m pp. 1303-1308

20 Annual Monitor 1840

21 Wigham (1842); DQB

22 RG 6/226, /1065, /1271; Annual Monitor

Suggestions for further research

While there may still be scope for new information to be derived from the British Newspaper Archive, I think that there are otherwise no obvious further lines of enquiry, for this page.

Richardson page | Family history home page | Website home page

This page was last revised on 2025-11-11.

© 2000–2025 Benjamin S. Beck