Hand toolsThe use of hand-made stone tools pre-dates Homo sapiens.

|

ClothingThe earliest surviving footwear appears to predate any other form of surviving clothing. These are the Fort Rock sandals, the first of which were found during excavations in the 1930s. Woven from sagebrush bark and other fibres, they were found above and below volcanic ash deposited by the explosion of Mt Mazama, which created Crater Lake 7600 years ago, in Oregon. All directly dated (via AMS 14C) Fort Rock sandals range in age from 10,200 cal. Before Present to c. 9300 cal. BP. [Great Basin Sandals; Connolly and Barker]

(© UO Museum of Natural and Cultural History) The oldest known piece of woven clothing is the Tarkhan Dress, a linen garment discovered in the Tarkhan cemetery south of Cairo. The most recent radiocarbon testing (in 2015) found that the dress dates from between 3482 and 3102 BCE, making it well over 5000 years old. The dress has a weave of 22–23 warps per cm, and 13–14 wefts per cm, creating a grey stripe in the warp, which may have been for a decorative effect.The main body of the dress was a 76 cm wide straight piece of material. The hem of the dress is missing, leaving the original length unknown.

Tarkhan Dress, coded UC28614B in the collection of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London. Credit: Getty Images

|

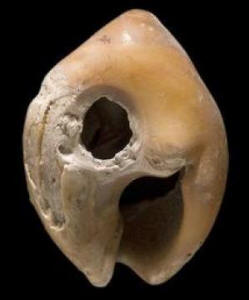

Personal adornment47 Nassarius shell beads that may date from as much as 110,000 BP were found in 2009 in a limestone cave at the Grotte des Pigeons at Taforalt in Eastern Morocco. Most of them are perforated and some are covered in red ochre. These are probably the earliest-known bodily adornments. [ScienceDaily]

(Image courtesy of University of Oxford) |

TattoosAlthough Ötzi the Iceman—the natural mummy, found in 1991, of a man who lived about 5300 years ago (now on display in the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, north Italy)—had 61 carbon tattoos on his body, it's not certain that these were for bodily adornment, as they may have been related to treatments for the relief of arthritic pain. [Deter-Wolf] In 2018 it was reported that infrared imaging had confirmed that figurative tattoos were also present on two pre-dynastic mummies held in the British Museum, including the famous Gebelein Man A, EA 32751, which has a tattoo on its upper right arm depicting two horned animals facing toward the front of the body. These mummies are said to be approximately contemporary with Ötzi. [Friedman et al., which includes a rather indistinct image taken under infrared light] The image below is of a tattoo on the

right arm of a Scythian chief whose mummy was discovered in Barrow no

2 at Pazyryk,

Russia, in 1949. His body was almost completely covered in tattoos, which were

made in the 5th century BCE. Generally, the tattoos are poorly

preserved, but are clearest on the right arm which, from wrist to

shoulder,

(Image from the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg) All

|

Art

(Photo: Riaan Rifkin) |

|

In July 2024 it was reported in Nature that rock art depicting human-like figures interacting with a pig, from Leang Karampuang, Sulawesi, Indonesia, was painted at least 51,200 years ago. This is now the earliest known surviving example of representational art, and visual story telling, in the world. [Zimmer; Bower]

(Photostitched panorama of the rock art panel, with photographs enhanced using DStretch_ac_lds_cb; from Nature ) |

|

Self-portrait, with autograph signature A sketch in rust-red drawn on a limestone ostracon (a piece of broken pottery) represents the self-portrait of the scribe, Sesh, wearing a knee-length kilt, his arms raised to present a papyrus roll and possibly a writing palette. The sketch is signed with the hieroglyph of 'scribe', consisting of a palette with wells for red and black ink, shoulder strap, water pot and reed pen. Measuring 11 x 12 cm, it was created in Deir-el-Medina, Western Thebes, 19th or 20th dynasty, c. 1292–1069 BCE, and excavated there, c. 1975. It is preserved in the Schøyen Collection (MS 1695). [From Cave Paintings to the Internet]

Schøyen Collection MS 1695 There is a possible earlier contender: a stele carved in about 1365 BCE, now in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin, depicts the pharaoh Akhenaten's chief sculptor, Bek, and his wife Taheret. It is likely that Bek produced the work himself. An image may be found here.

|

|

|

Portrait This image, carved in mammoth ivory 26,000 years ago, was found found in the Czech Republic at Dolní Věstonice, Moravia. Exhibited at the British Museum in London in the spring of 2013, it was widely publicised as the world's earliest known portrait. It shows a woman with her hair drawn up on the top of her head, with a fringe across her brow (or possibly wearing a fur hat). Although earlier images of people survive, this is seen as the first actual portrait of an individual person because of the distinctiveness of the features depicted. The British Museum's curator Jill Cook said, "The reason we say it is a portrait is because she has absolutely individual characteristics. She has one beautifully engraved eye; on the other, the lid comes over and there's just a slit. Perhaps she had a stroke, or a palsy, or was injured in some way. In any case, she had a dodgy eye. And she has a little dimple in her chin: this is an image of a real, living woman." [British Museum, The Guardian]

The earliest-known realistic portrait of a named individual, taken from life, has been said to be a portrait-statue including Queen Mertetefs, wife of Seneferu, the last king of third dynasty Egypt, and wife, by her second marriage, to Khufu, the first king of the fourth dynasty, the builder of the Great Pyramid. The statue is one of a limestone group of three figures representing Mertetefs, her ka (an aspect of her soul), and a priest named Kennu, who was her private secretary. The queen is depicted with buff flesh-tints and black hair. [Edwards 1891: 135-6] The historical information given by Edwards is confusing, and doesn't correspond with current interpretation. On the assumption that by "Seneferu" is meant Sneferu, the first king of fourth dynasty Egypt, there doesn't appear to be a wife named Mertetefs, although his "main wife" is said to have been Hetepheres I, who was the mother of Khufu (although this is now contested). It's most likely, though, that by "Mertetefs" is meant Meritites I; the latter was a daughter of Sneferu and the wife of Khufu. Almost certainly the portrait described by Edwards is the one pictured here, identified as Meritites and her son Shenou. This statue is held by the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, as stated by Edwards. [Bubastis]

(Photography: C. Smeesters) The earliest-known portrait of a named individual, the realism of which has been verified by facial reconstruction of their skull, is on the painted terracotta sarcophagus of an Etruscan noblewoman named Seianti Hanunia Tesnasa, who died about 2200 years ago in central Italy. The sarcophagus, on which she is named, bears a life-size sculpture of a middle-aged woman reclining and holding a mirror. Both the sarcophagus and the bones housed within are now in the British Museum. The facial reconstruction from her skull was made by Richard Neave.

(Image: British Museum)

|

|

Musical instrument Flutes made from bird bone and mammoth ivory, discovered by an Oxford University team led by Prof. Tom Higham in the Geißenklösterle Cave in Germany's Swabian Jura, have been carbon-dated to between 42,000 and 43,000 before the present, making them the earliest musical instruments ever discovered. [Journal of Human Evolution, BBC News]

|

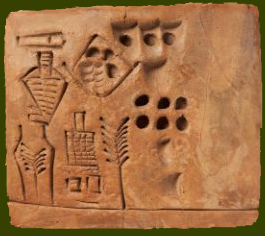

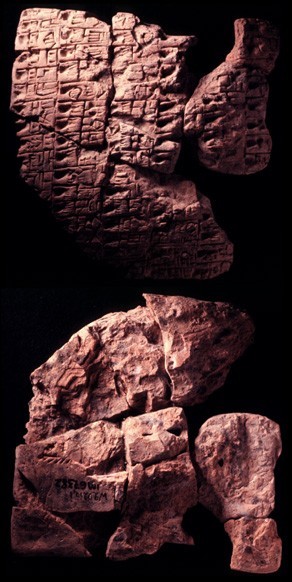

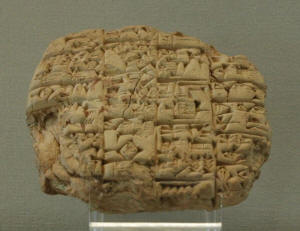

Personal name (male)Scorpion I was the first of two kings of Upper Egypt with this name. He reigned during the Protodynastic Period, 3200–3000 BCE. The name may refer to the scorpion goddess Serket. He is believed to have lived in Thinis a century or two before the rule of the better known King Scorpion of Nekhen and is presumably the first true king of Upper Egypt. To him belongs the U-j tomb found in the royal cemetery of Abydos where Thinite kings were buried. Earlier names have been identified as possible kings, but it's not certain that these don't represent gods rather than kings, or even place names. Possibly the earliest of these in sequence is referred to as 'Oryx Standard'. If names only known by their graphic representation are discounted, the earliest-known male name is that of Iry-Hor, a pre-dynastic king of Upper Egypt, who reigned in the early 32nd century BCE. The earliest names of non-royal individuals may be some of those recorded on Sumerian clay tablets, such as the slave-owner Gal-Sal and his two slaves Enpap-x and Sukkalgir (3200–3100 BCE). The Kushim clay tablet, sold at auction in London in July 2020, and dating from the 31st century BCE, includes the pictographic symbols for KU-SIM, believed to be the name of the scribe who recorded the beer-making transaction to which it refers. Publicity relating to the sale described it as "the earliest known record of any personal name in history," but it's not certain that it's the scribe's name rather than his title.

Personal name (female)The earliest woman in history whose name is known is Neithhotep, consort of Narmer, First Dynasty pharaoh of Egypt, and mother to pharaoh Hor-Aha. She lived around the late 32nd century BCE. Dynasty 00; Raffaele; Odenwald

|

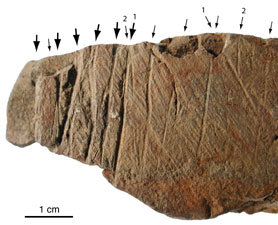

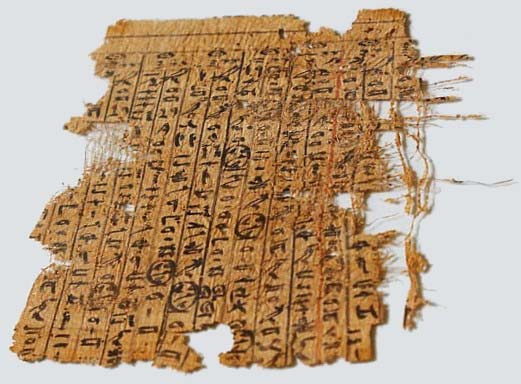

Written records

The Jiahu tortoiseshells

|

|

Accession no AO 4238, The Louvre—Department of Oriental Antiquities, Richelieu, ground floor, room 1a

|

|

Autograph signature See above.

|

|

|