Whole bodies

The most ancient surviving entire human body is

the mummy number EA 32751, formerly known as 'Ginger', and more

formally as Gebelein Man, radiocarbon-dated to 3341–3017 BCE. Currently

on display in Room 64 in the British Museum in London, Gebelein Man is thought

to have been discovered buried in desert sand in Gebelein in Egypt where

conditions can naturally preserve bodies, as the hot and dry sand

naturally absorbs the water that constitutes 75% of the human weight.

Without this moisture bacteria can't breed and cause decay, and so the

body is preserved. Though EA 32751's mummification may have been wholly

natural, since he was buried with pottery vessels it's likely that the

mummification was a result of the preservation techniques of those who

buried him. Stones may have been piled on top of the grave to prevent

the corpse from being eaten by jackals and other scavengers, and the

pottery might have held food and drink which may have been placed with

the body to sustain the deceased during the journey to the after life. A

CT scan in 2012 established that the body was that of a young man aged

18–21, who had been murdered by a stab to the back. [British

Museum;

BM blog;

Friedman et al.]

Mummy EA 32751

(Photo: © The

Trustees of the British Museum)

|

Body parts

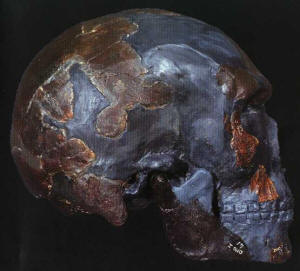

The most ancient mummified human head is the well

preserved naturally mummified head found in 1936 by Justiniano Torres

Aparicio, with two other mummies, at the site

of Inca Cueva #4, level 1A, at 3680 m.o.s.l. [sic,

but I think this must mean metres above sea level], in the

Quebrada of Chulin (Prov. of Jujuy, Argentina). A sample

of temporal skin from the head of Chulina has been radiocarbon

dated as having a calibrated age of 6080 ± 100 years (within 82%

probability). [Dubal]

The naturally mummified human head labelled J.T.A.-240

in the Museum Torres

Aparicio (Photo: L. Dubal)

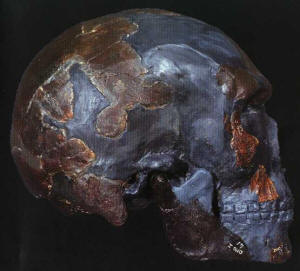

The remains of the world's oldest human

brain,

estimated to be over 5,000 years old, were found in 2009 in a cave in

south-eastern Armenia. An analysis performed by the Keck Carbon Cycle

Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at the University of

California, Irvine, confirmed that one of three human skulls found at

the site contains particles of a human brain dating to around the first

quarter of the 4th millennium BCE. The team in Armenia, comprising 26

specialists from Ireland, the United States and Armenia, had been

excavating the three-chamber cave where the brain was found since 2007.

The skull with the brain was found in a chamber

that contained three buried ceramic vessels containing the skulls of

three women, about 11 to 16 years old. The cave's damp climate helped

preserve red and white blood cells in the brain remains. What part of the brain the 9 x 7 cm brain fragment

comes from is still being determined. Microscopic analysis revealed blood vessels and traces of a brain hæmorrhage, perhaps caused by a blow to the head. [Abrahamyan]

|

Fossilised bones

The earliest known fossilised bones of Homo

sapiens are known as Omo 1, having been found by Richard Leakey, between

1967 and 1974, at a site near the Omo River, in south-western Ethiopia.

Their dating was significantly revised in January 2022, and they are now

considered to be 230,000 years old, give or take 22,000 years. [Nature,

Journal of Human Evolution]

In 2017 it was announced that fossil

bones, teeth, and skulls, from five individuals, had been excavated at

Jebel Irhoud in Morocco which have been dated by hi-tech methods to be

between 300,000 and 350,000 years old. They are anatomically clearly H. sapiens.

[Ghosh]

Omo 1

(Photo: Michael Day) |

Hair

The oldest surviving human hair is found on the

Chinchorro mummies of Chile, the oldest of which—the so-called 'Black

Mummies' (given a clay mask coated with black manganese)—date to up to 5000 years before the present. [Archaeology]

In 2009 much older hair was recovered from

fossilized hyena dung found in Gladysvale Cave, near Johannesburg, South

Africa. Dating of the cave's limestone layers showed that the dung had

been deposited some time between 257,000 and 195,000 years ago. It is

not known, however, whether the hair is from H. sapiens or the coeval

H. heidelbergensis. [Hoffman,

Journal of Archaeological Science]

5000-year-old remains of a woman, mummified in the black style and

surrounded by whalebone,

recovered from the site of El Morro in downtown

Arica, Chile, in 1983

(Photo: © Philippe Plailly / EURELIOS) |

DNA

In April 2021 it was announced that entire genomes have been sequenced

for three male individuals dated to between 45,930 and 42,580 years ago,

from Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria. All three had approximately 3.8%

Neanderthal ancestry, leading researchers to conclude that they were in

fact older than the previously sequenced genome from Ust'-Ishim in

western Siberia; two had Neanderthal ancestors about seven generations

back, and one—individual F6-620—had a Neanderthal ancestor less than six

generations back. [Nature,

Max

Planck Institute]

The most ancient DNA found in a living person was first identified in

2013, with the publication of an article in the

American Journal of Human Genetics, released on 7 March. The DNA

analysis of an African-American male from South Carolina was found to

contain single-nucleotide polymorphisms that contained vestigial

remnants of mutations of the Y chromosome that were estimated by an

international group of geneticists to have a time to the most recent

common ancestor corresponding to 338,000 years ago. This appreciably

predates the age of the earliest Homo sapiens fossils. [Discovery

News;

Examiner] |

Blood

Debate continues around the validity of

conclusions drawn from the analysis of blood protein residues on stone

tools. However, evidence of human blood does appear to have been found

on stone tools from the De Long Mountains of north-western Alaska,

believed to date from between 9570 and 8000 Before Present. [Arctic,

Vish]

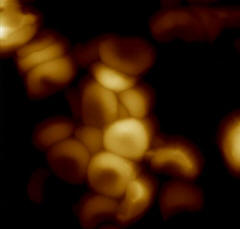

In May 2012 it was reported that actual red blood

cells had been recovered from the wounds on the body of the famous

Tyrolean iceman, Ötzi. [Janko,

Stark, and Zink]

Menstrual blood was recovered in 2007 from

woven aprons worn by Native American women in SE Utah and northern

Arizona over a period extending back to 2400 BP. [Quids]

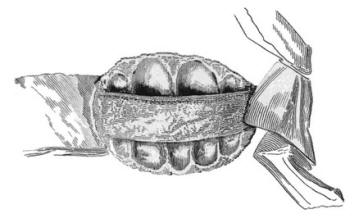

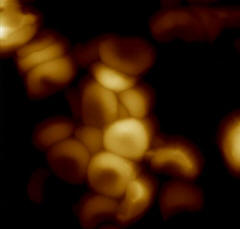

Red

blood cells recovered from Ötzi

the Iceman

(Photo: J. Roy. Soc. Interface)

|

Saliva

In 2019 an international

team of researchers successfully extracted sufficient DNA from a chewed

piece of birch pitch from Syltholm, on the island of Lolland, Denmark,

that they were able to recover a complete ancient human genome, as well

as microbial DNA reflecting the oral microbiome of the person who chewed

the pitch, as even plant and animal DNA that may have derived from a

recent meal. The pitch has a calibrated date of 5858–5661 BP. [Jensen et

al., Nature]

The same year human DNA

samples were extracted from chewed pitch dating to 9880–9540 BP, from

Huseby Klev, in western Sweden, although no whole genomes have been

reported. [Kashuba et al,

Nature]

|

Urine

In 2004 Greenwich workmen found a sealed jug

about 1.5m below ground. It was a bellarmine—a salt-glazed jar made in

the Netherlands or Germany, stamped with the face of Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino. When the jug was shaken it splashed and rattled, and the

Greenwich Maritime Trust asked retired chemist Alan Massey to study it.

Immediate X-ray revealed pins and nails stuck in

the neck, consistent with the jug having been buried upside down. CT

scans at Liverpool University showed it to be half-filled with liquid.

It was clear that this was a witch bottle.

Liquid was drawn through the cork of the

Greenwich bottle with a long-needled syringe. Complex chemical studies

that included recording a proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum,

and then gas chromatography / mass spectrometry analysis of organic

acids by Richard Cole (Leicester Royal Infirmary) and inorganic analysis

by Helen Taylor (British Geological Survey), allow Massey to say that

the liquid "is unequivocally human urine". Past claims for urine in

witch bottles have rested solely on inorganic material.

Cole identified cotinine, a metabolite of

nicotine: the urine had been passed by a smoker. [British

Archaeology]

CT scan of a 17th century 'witch bottle', showing human urine, pins and nails

(Photo: Mike Pitts / British Archaeology)

|

Faeces

A 2019

report

on 'Middle Stone Age humans in high-altitude Africa' reports "the

massive presence of human feces" at Fincha Habera rock shelter in

southern Ethiopia, dating from 47,000 to 31,000 years ago.

The earliest dateable human coprolites

(fossilized faeces) I've so far succeeded in locating on the Internet

were found at Wadi Kubbaniya in southern Egypt, and originate from

between 18,500 and 17,000 BP. [The

Antiquity of Man]

Actual desiccated paleofecal matter (not

fossilized) has survived in some very dry sites, such as the western

United States and Mexico. Some such matter, from Hidden Cave, Nevada,

has been dated to 3700–3400 BP. [Thorn]

The examples illustrated are from Hinds Cave, Texas, dated only as more

than 2000 years old. [Poinar

et al.]

The earliest faeces from a known, named,

individual is in the form of a lump found in a latrine box in 1937 which

was excavated in Aalborg, Denmark. The latrine was known to have been

used only by bishop Jens Bircherod (bishop there from 1694 to 1708),

whose manor was being excavated, and his wife. Analysis showed he had

eaten a cosmopolitan diet including grapes, cloudberries, figs, nuts,

and pepper, as well as buckwheat, which was known to be a local

speciality on the Danish island of Funen where the bishop grew up. The

faecal evidence of his diet is consistent with the opulent dinners he

noted in his diaries. [msn;

an image is to be found

here]

|

Semen

Semen can be cryogenically preserved, and in 2007

a baby was born whose father's sperm had been stored for 22 years, which

still appears to be the record. [Planer]

However, the British Human

Fertilisation & Embryology Authority states that in certain

circumstances a storage period of up to 55 years is permissible.

According to D.P. Lyle's Forensics for Dummies, 2nd edition,

2016, "dried semen stains can remain identifiable and usable for DNA

analysis for many years. Just ask Bill about Monica's blue dress." |

Milk, tears, snot

No information located.

|

Full references for printed works

Joanna

Ebenstein (2016) The Anatomical Venus. London: Thames

& Hudson

Paul Pettit

(2013) 'The Rise of Modern Humans', in Chris Scarre, ed.

(2013) The Human Past. World Prehistory & the Development

of Human Societies. 3rd edn, London: Thames & Hudson

Julius von

Schlosser (1910–1911) 'History of Portraiture in Wax'

('Geschichte der Porträtbildnerei in Wachs'), translated as

an appendix in Roberta Panzanelli, ed. (2008) Ephemeral

Bodies. Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure. Los Angeles:

Getty Research Institute

|