First photo |

|||||

1. The technology |

2. The human subject |

||||

First photo of a person |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Boulevard du Temple, Paris, 3. Arondissement is the earliest known photograph of a human being. The daguerreotype was taken in Paris by Louis Daguerre (1787–1851), on a date that has been calculated as between 24 April and 4 May 1838. It is of a busy street, but because exposure time was over ten minutes, the city traffic was moving too much to appear. The exception is a man in the bottom left corner, who stood still getting his boots polished long enough to show. Less discernible, but also visible, is the boot black. As Geoffrey Batchen has noted, this is therefore also the first photo to illustrate both labour and class difference. See also Jenkins, who notes the possibility that there are one or two other people also discernible. Daguerre gave a triptych of daguerreotypes, of which this was one (with another of the same view, taken later in the day), to King Ludwig I of Bavaria, and they were displayed at the Arts Association in Munich from 20 October 1839. Eventually they came into the custody of the Fotomuseum in Munich, where in the 1970s an attempt at cleaning succeeded in erasing the images. The image as seen today is a reproduction of a photographic copy made by Beaumont Newhall, the historian of photography, in 1937. [History of Art: History of Photography] NB Although the strongest evidence supports this image, an interesting case has been made for a daguerreotype image made by Daguerre and Mathurin-Joseph Fordos, of the Pont Neuf in Paris, and now preserved in the Musée des Arts et Métiers. It's argued that this could actually date from the summer of 1837, but at any event prior to the Boulevard du Temple image. See Gunthert, or the same page translated. In any case, it would appear that the Pont Neuf image is the earliest of which the original daguerreotype survives unscathed. For an extended listing on this theme, see this page by my collaborator, arago86.

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

First portrait photo of a person |

|||||

|

|||||

|

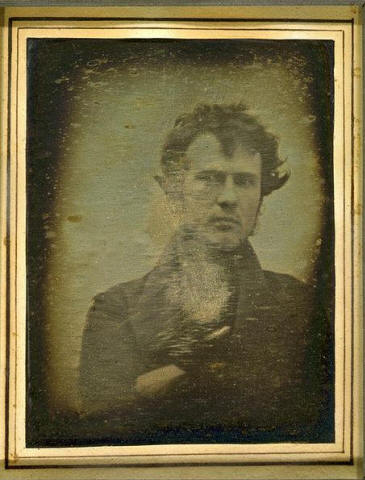

According to John Johnson (1813–1871), the first daguerreotype portrait was of himself, made in New York by Alexander S. Wolcott (1804–1844) on 6 or 7 October 1839. This was tiny (according to the Gernsheims, it was on a ⅜in plate), and has not survived. (Hannavy) However, Howard R. McManus has convincingly argued that John William Draper (1811–1882), professor of chemistry at the University of New York, accomplished successful portrait daguerreotypes as early as 23 September 1839, the first such being of his assistant William Henry Goode, taken in the university chapel. (McManus—First) Draper's daguerreotype of Goode is said to have still been in existence in 1890. (Eder) McManus includes an image of a flawed daguerreotype plate (from his own collection), in which the subject is very difficult to make out, but which he speculates may in fact be an experimental portrait photograph of William Henry Goode, from 22 or 23 September 1839. Generally accepted as the earliest surviving photographic portrait image of a human ever produced is the approximately quarter plate daguerreotype by Robert Cornelius [1809–1893], a head-and-shoulders [self-]portrait, facing front, with arms crossed (above), dating from 1839 [Oct. or Nov.]. [LC-USZC4-5001 DLC]. Written on the paper backing is "The first light picture ever taken. 1839." The photograph, now at the Library of Congress in Washington DC, was taken outside his place of business on 8th Street between Market and Chestnut, in Philadelphia. The Cornelius daguerreotype is not uncontested as the earliest surviving photographic portrait. Another strong contender is the self-portrait of the Baltimore daguerreotypist Henry Fitz (1808–1863), now held by the Smithsonian, which also dates from late 1839. This is reproduced in Newhall, and in Wikimedia Commons. NB An interesting argument has been made for an earlier candidate than any of these, a daguerreotype portrait of a M. Huet, apparently by Daguerre himself, and dated 1837 on the back. This image is in the collection of Marc Pagneux. It does seem established that Daguerre was experimenting with portraits in 1837, and the portrait could be one such. See Gunthert, or the same page translated; and Gunthert & Roquencourt, (translated); and Wood.

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

First photo, and first portrait photo, of a woman |

|||||

|

|||||

|

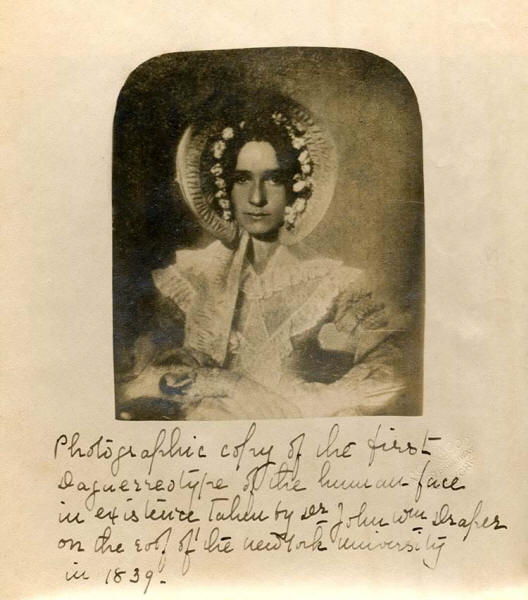

The Belgian Jean Baptiste Ambroise Marcellin Jobard (1792–1861) is said to have made a portrait of a young woman asleep on a sofa in October 1839, but if so this image has been lost. (Directory of Belgian Photographers) In 1855 the photographer Samuel Finley Breese Morse (1791–1872) claimed that he had taken full-length portrait daguerreotypes of his daughter, and also photographs of her in groups with some of her young friends, in September or the beginning of October 1839. All that survives is a crude wood-engraving of a double portrait, reproduced in Root. This image of Dorothy Catherine Draper (1807–1901) is a copy of the earliest surviving photograph of a woman. John William Draper (1811–1882), professor of chemistry at the University of New York, built his own camera and made this portrait of his sister in June 1840 (notwithstanding the inscription), after a 65-second exposure. The image is from the Westchester Archives. The original daguerreotype is now held by the Spencer Museum of Art, in Lawrence, Kansas, on indefinite loan from the Kansas State Historical Society. An image of the daguerreotype itself (dated to 1840 by the Museum) may be found here; this graphically shows the damage caused by an attempt at cleaning it in 1934, described here. That said, it appears that the damaged daguerreotype itself was a copy, and at least three other daguerreian copies are now known. (McManus—Famous)

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

Earliest-born person to be photographed |

|||||

|

|||||

|

The earliest-born person to be photographed was probably John Adams, who was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, on 21 January 1744/5, the son of Captain Thomas Adams and Lydia Chadwick. A shoemaker, he died on 26 March 1849, in Harford, Pennsylvania, aged 104, having made himself a new pair of shoes in his final year. A photographic copy of a daguerreotype (the whereabouts of the original being unknown) is in the possession of the Susquehanna County Historical Society. This image is from Taylor (2013). His date of birth is confirmed by the New England Historic Genealogical Society's Vital Records of Worcester, Massachusetts [documented at Ancestry]. Remarkably, John Adams's first wife, Joanna Munroe, was second cousin to Mary (Munroe) Sanderson. [Wikitree] Another contender (to me unconvincing) is Baltus Stone, an American revolutionary war veteran, of whom an 1846 quarter-plate daguerreotype was sold at Sotheby's, New York, on 6 October 2010, for $16,250. A manuscript inscription laid over the case lining states that Stone was born in October 1744. The catalogue notes quote from an obituary printed in the National Intelligencer for 27 October 1846, in which it was claimed that the deceased was 103 years and 16 days old at the time of his death on 22 October, which would suggest a birth year of 1743. However the Copes-Bissett family Bible (recording the family of Baltus Stone's presumed daughter Hannah, who married George Vessels Copes) states that "Bolltes Stone was born the 7th of June in the year of our Lord 1747". Additionally, in Stone's own declaration before the district court, when claiming his Revolutionary War Pension on 8 September 1820, he is said to be "aged sixty six years"—i.e. implying a birth year of 1754. It is not unlikely that his great age had been somewhat inflated by the time of his death. [Ahnentafel of Charles William Wolfram; Revolutionary War Pensions Files, file S41190] The New York Historical Society has a 1/6th plate daguerreotype of a slave named Caesar, taken in 1851, at which date the subject was supposedly 114 years old (New York Historical Society Cased Photograph File, PR-012-2-323). If true, his birth year—approximately 1737—would easily make him front-runner. However, no contemporary evidence for his age or birth year is presented. The catalogue states that a typewritten slip mounted on the verso of the frame reads: "Ceasar [i.e. Caesar], born a slave of Van R. [Rensselaer] Nicoll, son of William, in 1737 at Bethlehem, N.Y., where he died in 1852. The last slave to die in the North. This daguerreotype was taken in 1851. His 2nd master was Francis Nicoll, son of Van R. Nicoll and his 3rd master Wm. Nicoll Sill, grandson of Francis who left all to his wife Margaret Sill . . ." [NYHS catalogue]. Taylor has a little more history of Caesar's ownership, but adds nothing confirming his year of birth. The NYHS have advised that "His date of birth can't really be confirmed." [private communication] The only public record so far located, giving any credence at all to Caesar's age, is the 7 Aug 1850 entry in the US census for the town of Bethlehem, Albany County, New York, which records "Cesar Nicholls", aged 110, in the household of Margaret Sill. [Thanks to Nate Kelley for this reference.] For an extended listing on this theme, see this page by my collaborator, arago86.

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

Earliest-born woman to be photographed |

|||||

%20Sanderson.jpg) Image originally from the Facebook page of the Lexington Historical Society, archived here | |||||

|

Mary (Munroe) Sanderson was said, during her lifetime, to have been born on 10 October 1748, and baptised on 23 October that year, in Lexington, Massachusetts, USA, the seventh child of William and Rebecca (Locke) Munroe. She was married on 27 October 1722 to Samuel Sanderson, a cabinet maker. She died aged 104 on 15 October 1852, at East Lexington, her body being interred at the old burying ground in Lexington. [John Godwin Locke (1853) Book of the Lockes, p367] Remarkably, Mary Munroe was second cousin to the first wife of John Adams. [Wikitree] For an extended listing on this theme, see this page by my collaborator, arago86.

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

First passport photo |

|||||

|

|||||

|

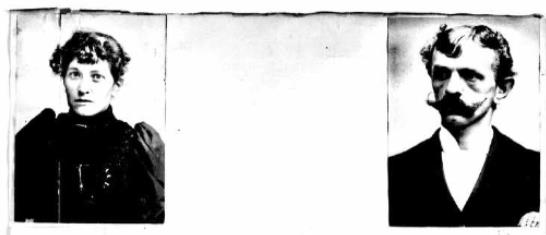

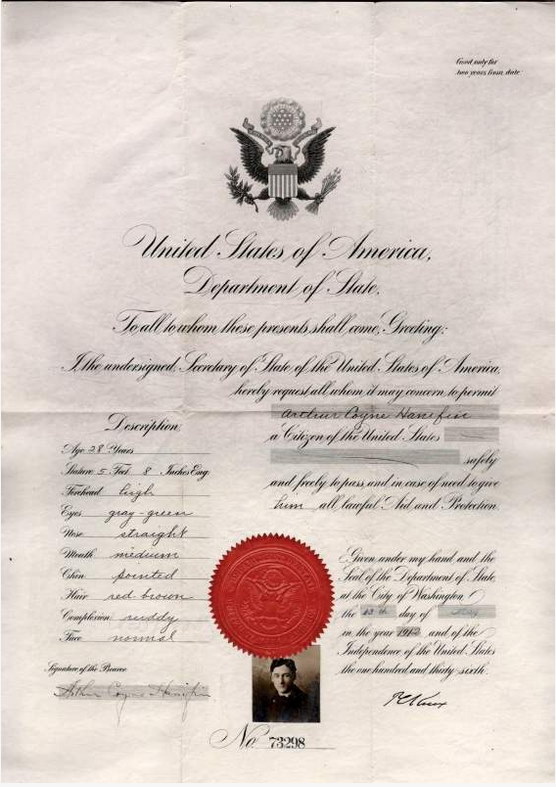

The US passport shown above is for Arthur Coyne Hanifin, and was issued on 13 May 1912, well before photographs on passports were mandatory. It includes easily the earliest passport photo, actually fixed to a passport, yet located. [passport-collector]

However portrait photos were frequently attached to passport applications appreciably earlier than that, the earliest so far located being those of Charles C.J. Wirz and his wife Caroline (above), for a passport issued in California on 11 October 1897. [passport application] The USA was the first country to require the use of photographs on passports, in 1914, followed shortly after by the UK and the rest of the British Empire, from February 1915. [Pietras; Parkinson] UK passports number 1-99 are held at the National Archives (TNA: FO 115/1953), but are unfit for production, as mould damaged. [TNA]

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

First mug shot |

|||||

|

|||||

|

The earliest surviving police photographs of criminals were daguerreotypes taken in Brussels in 1843 or 1844. There are four such, of which this is said to date from 1843. However, the Philadelphia Public Ledger for 30 November 1841 reported that persons arrested in France were already being photographed at that date, for future reference. It doesn't appear that any of these survive. [Buckland; Nichols; Moenssens] |

|||||

|

|||||

|

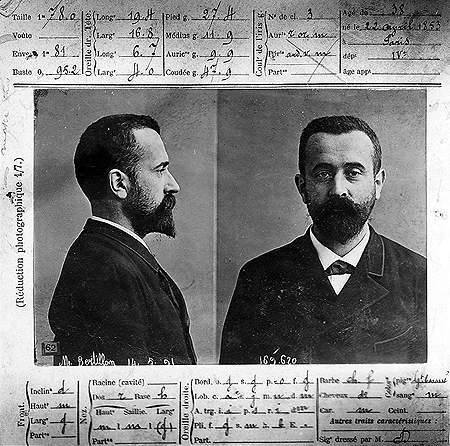

The standardisation of mug shots, with a profile view as well as a full face, was developed by 1883 by Alphonse Bertillon (1853–1914). The earliest so far located is this 1891 portrait of Bertillon himself. [Oltuski; Moenssens]

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

| © 2009–2025 Benjamin S. Beck |

If you know of any earlier examples, please contact me.

|

|