First movie |

|||||

1. The technology |

2. The human subject |

||||

|

|

|||||

First movie |

|||||

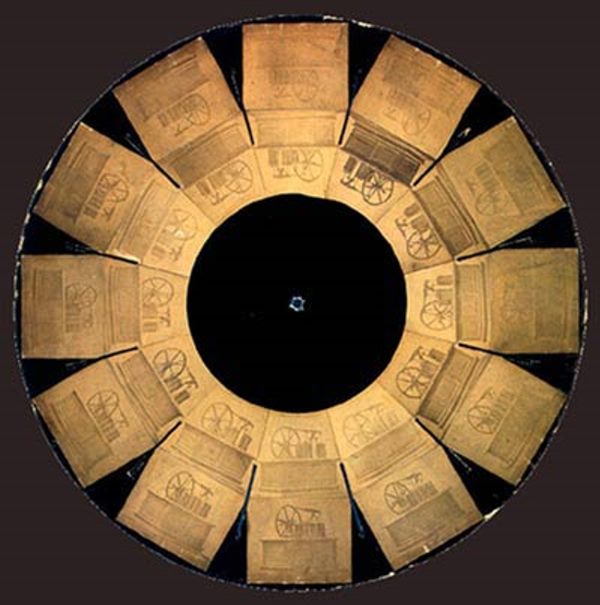

Jules Duboscq, bioscope disc, c. 1852. Coll. Joseph Plateau, Musée de l'Histoire des Sciences, University of Ghent, Belgium, catalogue no. MW96/1859. |

|||||

|

On 12 November 1852 Louis Jules Duboscq (1817–1886) patented the 'stereoscope-fantascope or Bioscope', which apparently combined the properties of the stereoscope with those of the phenakistoscope. Twelve pairs of stereoscopic images were placed round the surface of a disc, and when spun the images were viewed by lenses or mirrors. The image above is of the only surviving Bioscope disc. No example of the instrument itself has yet been found. The image has recently been effectively and convincingly digitally processed into a 3D motion video, by Denis Pellerin; the video was shown at a presentation at Kings College, London, in October 2016, and is now available online. [Pellerin; Pellerin, ed. May, 2021]

|

|||||

|

In 1872 Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904) began to make instantaneous photographs of a horse trotting (the 1872 photographs have not been found, however). In 1877 he successfully photographed Leland Stanford's horse Occident in fast motion, though again no photographic images survive. During late 1877 and early 1878 he developed a technique for capturing sequential photographs of horses in motion. The first demonstration of Muybridge's method and equipment took place successfully on 15 June 1878, in the presence of the press, the negatives being developed only 20 minutes after the shoot. (A reporter had been present at preliminary run-throughs on 9 and 11 June.) Muybridge used a series of twelve stereoscopic cameras, 21 inches apart, to cover the 20 feet taken by one horse stride, taking pictures at 1/1000th of a second. The cameras were arranged parallel to the track, with trip-wires attached to each camera shutter triggered by the horse's hooves or (for wheeled vehicles) the passage of wheels. [The Complete Eadweard Muybridge: Chronology 1876–1880, Pop Art Machine, Riggins; Prodger; Tosi]

|

|||||

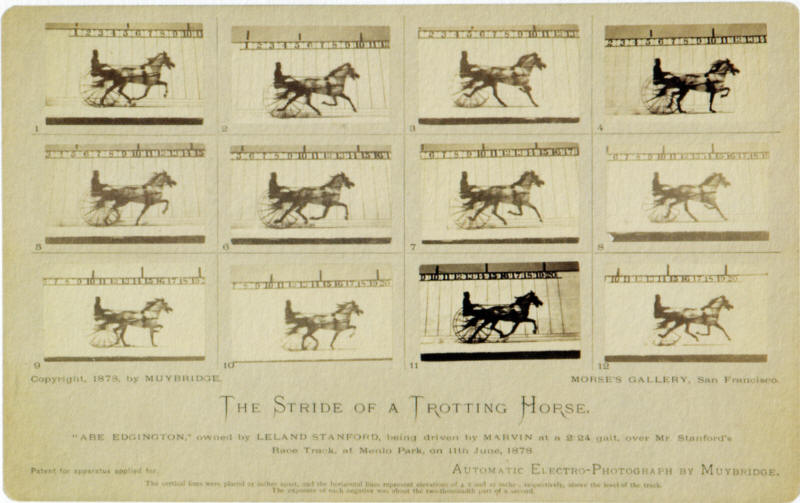

'The Stride of a Trotting Horse, "Abe Edgington," owned by Leland Stanford; being driven by Marvin, trotting at a 2:24 gait over Mr. Stanford's Race Track at Menlo Park, on 11th June, 1878'; reproduced from p. 85 of Brookman |

|||||

|

Muybridge's 1878 sessions confirmed for the first time that the hooves do all leave the ground simultaneously, and led to his publication of a series of cabinet cards called The Horse in Motion (not to be confused with the 1882 publication [copyright 1881], J.D.B. Stillman's The Horse in Motion). One of these cabinet cards, 'The Stride of the Trotting Horse, "Abe Edgington," owned by Leland Stanford; being driven by Marvin, trotting at a 2:24 gait over Mr. Stanford's Race Track at Menlo Park, on 11th June, 1878', is illustrated above. My own animation, below, appears to be the first made from this 11 June card, or at any rate the first uploaded to the Internet. At the date of upload [2016-03-30], all other Muybridge animations on the Internet have been made from sessions of later date. This 11 June animation may legitimately represent the first ever motion picture.

Historians of film, understandably emphasising the issue of projection, have shown particular interest in Muybridge's zoopraxiscope, which enabled projection of his sequence photographs. However, this device required the photographs to be repainted, to avoid distortion, so was not in fact projecting photographic images. It has been suggested, however, that Muybridge's decision to use twelve cameras may have been determined by the fact that zoetrope strips generally included twelve images, so he may have considered animation from the outset [although Braun suggests that the number was based on Oscar Rejlander's 1872–3 paper 'On Photographing Horses']; and when his 'Horse in Motion' pictures were first published in the Scientific American in October 1878 the editor suggested mounting them in a zoetrope. On 25 January 1879 the French magazine L'Illustration reported that Emile Duhousset, a writer on the horse, had in fact mounted Muybridge sequence photographs in a zoetrope, and was marketing strips of drawings based on these pictures. In similar fashion the editor of The Field also experimented with mounting Muybridge's photographs in a zoetrope, before finding greater success by mounting them in a praxinoscope. The Field subsequently marketed strips of silhouette images based on the photographs; possibly this statement relates to the Zoetrope band using Muybridge's photographs copyrighted and sold in England in 1879 by the naturalist William Bernhardt Tegetmeier. [Mozley, ed.; Rossell; Herbert, ed.]

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

First movie shot by a single camera onto a continuous band of paper film |

|||||

|

Roundhay Garden Scene is an approximately 2-second movie made in Britain in 1888 by inventor Louis Le Prince (1842–1890). It was recorded at 12 frames per second. According to Le Prince's son, Adolphe, it was filmed at Oakwood Grange, the home of Joseph and Sarah Whitley, in Roundhay, Leeds, West Yorkshire, on 14 October 1888. It was recorded on an 1885 Eastman Kodak paper base photographic film through Le Prince's single-lens combi camera-projector. [Spehr, p114] Le Prince's daughter, Marie, claimed that her father had projected films onto a wall of the Institute for the Deaf on Washington Heights, New York, NY, even earlier than this (between 1885 and 1887), and that some of these were taken with a single-lens camera-projector. This can't be independently verified, however, and in any case any such films no longer survive. [E. Milburn Scott in Fielding] David Nicholas Wilkinson's The First Film concludes that Le Prince probably did succeed in making motion pictures prior to October 1888, so Roundhay Garden Scene should probably be regarded as the earliest surviving, rather then first. Paul Fischer, in his recent biography of Le Prince, says that the first film taken on 14 October 1888 was actually the short sequence of his son Adolphe playing the melodeon. He has indicated [private communication] that this is probable, but unproven. It was in any case, apparently, shot at a lower frame rate than Roundhay Garden Scene, so probably doesn't qualify on this ground. It appears that only 19 frames survive, of which an animation can be found here.

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

First movie shot by a single camera onto a continuous band of celluloid film |

|||||

|

The earliest motion picture actually photographed onto celluloid was not made on a spooled band of film but onto a sheet of celluloid wrapped round a cylinder, around which the tiny images (⅛ inch diameter) were spiralled. This was Monkeyshines, No. 1, shot by William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson (1860–1935) and William Heise (1847–1910) for the Edison labs, around July 1889. ('Monkeyshines' was the generic name used by Dickson and his colleagues to identify these early tests. Although at least four monkeyshines appear to have been made, only three survive; the images in the other two were ¼ inch in diameter. The figure depicted is one of Edison's workmen, Fred Ott, wrapped in a white sheet tied in the middle, waving his arms.) [Spehr, pp141, 151, 210; Harold G. Bowen, in Fielding] The earliest movie photographed onto a spooled band of celluloid film is generally known as Dickson Greeting, a very brief experimental film made in the Photographic Building at Edison's Black Maria studio, West Orange, New Jersey, with the Edison-Dickson-Heise horizontal-feed kinetograph camera and viewer, using ¾ inch wide film, with the image in a circular aperture and small oval perforations along the lower side of each strip, the film moving horizontally. It was probably made in the spring of 1891, and was viewed in the kinetoscope by Mrs Edison's guests on Wednesday, 20 May that year, when she entertained the presidents of the Women's Clubs of America at Glenmont, the Edisons' home in Llewellyn Park. At least six other films were made during 1891, and it's not clear which was actually the earliest made—some could be as early as January 1891. These other films were: Duncan and Another, Blacksmith Shop; Monkey and Another, Boxing; Duncan or Devonald with Muslin Cloud; Duncan Smoking; Newark Athlete [aka Indian Club Swinger]; and Men Boxing. In all probability other films were made during this period, but it's assumed that they were failures, and as such not recorded. [Spehr, pp200-1, 208-9, 212]

| |||||

|

|

|||||

First panchromatic ciné film |

|||||

|

Eastman Kodak originally developed the first panchromatic ciné film for the Gaumont Chronochrome process, from the end of 1912. [Cherchi Usai, Brown] The earliest regular film production filmed on panchromatic negative film was The Headless Horseman (1922, dir. Edward D. Venturini). As of October 1954, the negative was at Eastman House in Rochester, New York. [C.E. Kenneth Mees, in Fielding]. The film is available on DVD.

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

First movie projected publicly |

|||||

|

According to Deac Rossell, there is strong evidence that the Hanover physics teacher, gymnastics instructor and chronophotographer Ernst Kohlrausch (1850–1923) projected moving pictures in public at a meeting of the North West German Gymnastics Teachers Association in winter 1893; four of his moving pictures are presented on YouTube, where it is said to be unclear that Kohlrausch projected public screenings before April 1898. The chronophotographer Ottomar Anschütz (1846–1907), using his Projecting Electrotachyscope, projected 40 different moving pictures of short duration on a huge screen measuring 19½ ft by 26¼ ft at the Post Office building in Berlin on 25, 29, and 30 November 1894. [Rossell; Albert Narath, in Fielding] The apparatus was installed at the old Reichstag building in Artillerie Street, Berlin, in February 1895, and the Anschütz chronophotographs were projected in a 300-seat hall there from 22 February through 30 March to a paying public. On 22 March 1895 the brothers August and Louis Lumière (1862–1954 and 1864–1948 respectively), together with their head mechanic Charles Moisson, gave a presentation of their cinématographe in Paris, to the Société d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie Nationale. The 46 second film they projected—La Sortie des usines Lumière—consists of a single scene depicting workers (mostly women) leaving the Lumière factory at 25 rue St Victor, Monplaisir, Lyon, France, three days previously. [Lamotte, Tavernier] Three separate versions of this film exist, often referred to as the 'one horse,' 'two horses,' and 'no horse' versions, in reference to a horse-drawn carriage that appears in the first two versions (pulled by one horse in the original). All three versions were included in the NTSC DVD of The Lumière Brothers First Films [now on YouTube]. As an aside, it's rather remarkable that in the 1895 showings the Lumière brothers also projected some of the earliest colour photographs made by the interferential process developed by Gabriel Lippmann. [Natalie Boulouch, in Hannouch, ed.]

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

First movie encoded in DNA and successfully retrieved |

|||||

|

In March 2017 it was announced that the 1895 Lumière film L'arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat had been successfully encoded in DNA, along with a full computer operating system, a $50 Amazon gift card, a computer virus, a Pioneer plaque and a 1948 study by information theorist Claude Shannon. The files were first compressed into a master file, and then the data was split into short strings of binary code. Using a technique called 'fountain codes', they randomly packaged the strings into 'droplets', and mapped the coding in each droplet to the four nucleotide bases of DNA. The algorithm deleted letter combinations known to create errors, and added a barcode to each droplet to aid the subsequent retrieval of the files. The research team generated, altogether, a digital list of 72,000 DNA strands, each 200 bases long, and sent it in a text file to a DNA-synthesis company, Twist Bioscience, that specializes in turning digital data into biological data. Two weeks later, they received a vial holding a speck of DNA molecules. To retrieve their files, they used modern sequencing technology to read the DNA, followed by software to translate the genetic code back into binary. Their files were recovered with zero errors. [Science Daily; Science].

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

First feature film (actuality) |

|||||

The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight (1897) |

|||||

|

The earliest actuality film of feature length, The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight—a prize fight that took place on 17 March 1897 at Carson City, Nevada, in which Bob Fitzsimmons, the underdog, beat James J. Corbett, the champion, with a controversial solar plexus punch in the 14th round—originally ran to 100 minutes. The first complete public presentation took place on 22 May the same year, at the Academy of Music in New York City. Under the direction of Enoch J. Rector (1863–1957), it was "one of the earliest individual productions to generate and sustain public commentary on the cinema". The film is sufficiently noteworthy that Dan Streible devotes a whole 44-page chapter to it. According to IMDB about a quarter of the film survives. Just over 19 minutes of footage is available on YouTube, in two parts (Part 1, Part 2).

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

First feature film (narrative) |

|||||

The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906) |

|||||

|

The Story of the Kelly Gang is generally regarded as the world's first narrative feature film. At 70 minutes, its length was unprecedented when it was released. The movie traces the life of the Australian bushranger and folk-hero, Ned Kelly. It was written and directed by Charles Tait (1868–1933). The film's approximate reel length was 4000 ft (1200m). It was released in Australia on 26 December 1906 and in the UK in January 1908. The film cost an estimated $2250 and was filmed in Melbourne. According to Bertrand, it was originally screened with actors providing dialogue behind the screen and sound effects simulating galloping horses, gun shots, and crowd noises. Until recently only about 10 minutes were known to have survived. In November 2006 the Australian National Film and Sound Archive released a new digital restoration which incorporated 11 minutes of material recently discovered in the UK. The restoration now is 17 minutes long and includes the key scene of Kelly's last stand. In 2007 The Story of the Kelly Gang was inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register as the world's first full-length feature film. [Return of the Kelly Gang] Nearly 16 minutes of footage may be viewed on YouTube, in two parts (Part 1, Part 2); much of Part 2 is severely damaged, and barely watchable. The earliest feature film currently known to survive at feature length is From the Manger to the Cross, directed by Sidney Olcott (1873–1949), and released in London on 3 October 1912. An NTSC DVD was released in 2003, mastered from a re-release print from around 1919. The film is now on YouTube. [Silent Era; IMDB]

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

First recording from broadcast television |

|||||

|

A few recordings have been recovered and restored from 'Phonovision' discs recorded by John Logie Baird in the late 1920s—moving pictures recorded onto 78rpm gramophone records. These were never played publicly at the time, probably because the quality was even worse than the images as transmitted. These are not considered here, as the images were not in fact recorded from broadcast television. [405 Alive; BFI TV Technology 1; BFI TV Technology 10; The Dawn of TV] Film was used in Baird's intermediate film television process, from 1932, and some of these films have survived. But these represent pre-recorded content, not off-air recording. [405 Alive; Shagawat] Dr Frank Grey of Bell Labs introduced tele-recording equipment for electronic TV in February 1929. The following year General Electric's labs in Schenectady, New York, captured experimental TV images on film. These very brief 1930 film clip frames still survive. They show a man as head and shoulders, as taken from GE's pioneer W2XCW station, which had started its first regularly scheduled telecasts in 1928. [Shagawat] By 1930 a disc system for home audio recording—Silvatone—was commercially available, and someone using this system in Ealing, London, used it to record 30-line television broadcasts off-air, using a medium wave receiver connected to the audio input of the recorder, but with no synchronisation information. One disc survives, of part of a BBC TV revue called Looking In, featuring dancing by six members of the Paramount Astoria Girls and broadcast on 21 April 1933. [BFI TV Technology 10; The Dawn of TV] The full recording lasts four minutes, but only a few seconds is played at The Dawn of TV. Eleven additional private off-air disc recordings of television broadcasts (The 'Marcus Games discs') also exist and have been restored, believed to date from the period 1932–1935. [BFI TV Technology 10; The Dawn of TV; Restoring Baird's Image]

|

|||||

|

|||||

| © 2009–2023 Benjamin S. Beck |

If you know of any earlier examples, please contact me.

|

|