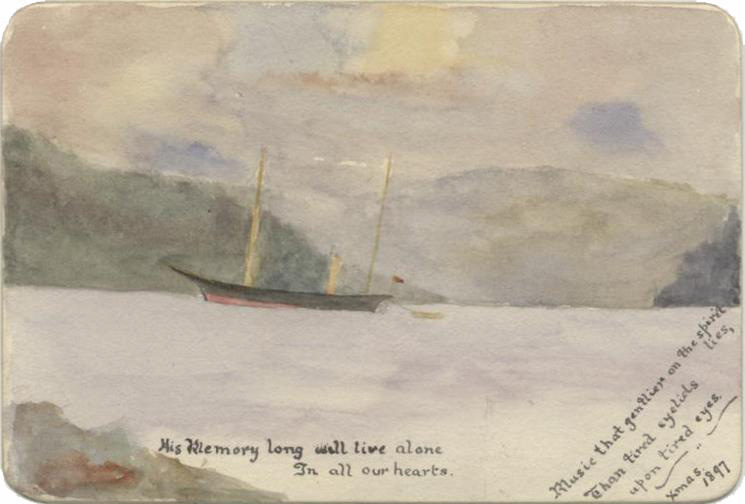

Letters from Frank Pollard to Mary Spence Watson(with nine from Mary to Frank, and one from Frank to Robert Spence Watson)Frank to Mary:Dalton Hall 5.XII.1897 Dear Mary, It was very good of you to let me read your letter to Arnold—I have felt it almost an intrusion upon something sacred, but have read it over and over again. Need I say how constantly I have thought of you during the last few days, and of your life with its aching sense of loss always there? Your letter to him helps me to see better, though I knew it well before, what Arnold must have been to you, and how blank the coming days must seem. My own sense of loss (and it is very great) gives me some little idea of yours. I miss him more than I can say, and every time I pass his door, I think of calling to see him or ask him to tea, and then remember the vacant room. I'm afraid I get little consolation from the ordinary religious talk at such a time. To me the only happy thing is to remember his pure and lovable and sympathetic heart—the memory and influence of which must be a treasure for ever. You must forgive me writing like this, as though my own loss could for one moment be compared with yours: but it is through this that I can enter a little into your grief, and wish, however vain it may be, to comfort you a little. I have got the picture which was so very kindly given me, hanging up now in my room—I was immensely grateful for it, but I don't think any memento will ever be needed. By the bye I almost think that our football pump, of which Arnold was the custodian, must have got packed up among his things. I hope everything was all right, in the boxes and things. Mr Fowler has been spending Sunday at the Hall, and we have had some delightful talks—he has been writing a bit of an account of the Griffin trip, in 'Blue and Gold' , the Sidcot Old Scholars' magazine—it is to appear in about ten days I think—I shall certainly get a copy—I wonder if you would like to see it. I hear there is some chance of Joe Wigham's getting over to a Griffin party at Mr West's in January: it' ll be great sport to see him again, and I expect he' ll bring his lantern slides. I should like immensely to see my brother's letter, if I might: I am sending back thy own herewith. If I had dared, I would have begun this letter as thou signed thyself there; but I thought I'd better not without leave from thee. May I? But I'm not sure that I want to. I wonder what the remark was thou began to make –'when you write to me' , just as I was coming away on Tuesday evening—thine very sincerely, Frank PS. I hope you are all keeping well, and are not utterly knocked up with the strain. How is Ruth? Please give my best regards to everybody. PPS. By the bye we were so grateful for the lunch on Wednesday: we had quite a luxurious time in the train. It is awfully difficult settling to work again—E.F.H. has quite given it up as a bad job. Mary to Frank:Nether Grange Alnmouth Northumberland 23.12.1897 Dear Frank, We are all here now, but Evie and Ernest, who are coming to-morrow. I hope you arrived home safely, but I expect you found the journey rather awkward, with your bad knee. Will you have to lie up all the holidays? I wish you could have come here, so that we might read to you and look after you, but I'm sure Mrs Pollard will do that much better than we could. You must come and stay with us sometime at home. This is a lovely house, and very comfortable. The baby is delighted with her new nursery. Father has not been at well—in fact he was in bed all yesterday, but I think this air will soon do him good. Somehow the least illness makes us so anxious now, and the other night Ruth and I were wakened by a telegram (about the Russian Bourtzeff) and really we hardly could open it—our nerves are still so queer. This house is close to the sea, and about a mile from the station. We left Tommy behind, but perhaps are going to send for him. I feel so utterly miserable that I don't seem to have anything to say. Mind you don't begin to try and walk too soon. I do hope you will soon be better, and that you will have a happy Christmas, and a very happy New Year. Yours very sincerely, Mary Spence Watson. [This letter enclosed a hand painted card of the Griffin in a Loch:]

Frank to Mary:Dalton Hall Victoria Park 11.1.1898 Dear Mary, Thanks muchly for your nice long letter—it refreshed me very much—I was beginning to think you were never going to write—I suppose it was only about ten days, but that seemed a tremendously long while—I'm so greedy you see. How very naughty of you to talk like that about being stupid and ignorant: just as though I couldn't mention scores of things that you know heaps about and I know nothing at all. The first thing that occurs to me, is how to write a three sheet letter, which shall be interesting and nice from beginning to end; the next is how to paint pictures of Scotch lochs for Christmas Cards. There are two things straight off, that I should like very much to do but can't, and you can. I got back to the Hall yesterday afternoon. My knee is getting on very well, and I am doing a bit of walking now, generally with a large stick. Dr Brown came to see it this morning, and is quite satisfied with it; I may do a little gentle walking. I am back in my own room now, which is a blessing, though it is a fearful way off everywhere, with a terrible array of steps to be gone up and down. Falkner came back today, and seems in good form I think, though rather tired with dances; he is full of his dancing, which he has been learning these holidays. Joe has been showing me his sister's and Miss Grace's photographs, and I am ordering about sixteen of them—many of them are very good indeed. Thanks for the receipt: my mother made some according to it, but the result though very nice wasn't much like the real original; for one thing it wouldn't go properly hard: I wonder what was wrong. What a funny idea of yours that the men always get the best of it; why, I thought it was a recognized fact that women always got their own way, and men had to do what they were told. I certainly never could get my own way on the Griffin—at any rate I always did what you told me, very meekly, whether it was not to drink any more tea, or to sing a song, or to be lazy and stay on board instead of going on shore. But perhaps you meant husbands and wives. I don't know whether this letter will find you at home, or whether you' ll have gone to Leicester—and you never sent your address! You are quite right in a way about the little Tommy, but you can imagine, can't you, why I wanted to have it. Tomorrow I am going to Birmingham to the Teachers' Conference. I'm afraid I shan't be able to get about to see the places they are going to visit, but that doesn't matter much—the main thing is the meetings, and seeing people. I am looking forward to hearing your sister's paper very much. Yes, I remember the cat at Dunvegan very well: I was rather in a rage that evening I fancy, which was probably Joe's fault or yours—it generally was: but I quite recovered I remember before going to sleep. There is to be a Griffin party at Penketh on Saturday, as perhaps you know: don't forget to be present in spirit if you can't be in the flesh. And what have I got to sing please? I have been reading heaps of novels in the holidays; among other Black's 'White Wings, a Yachting Romance' , which you' ve very likely met with—it's all about the parts we went to, and is very readable I think for those who' ve seen the places. And his picture of yachting life brought back very vividly the pleasures of our time there. Curiously enough two others that I read—Marion Crawford's Dr Claudius, and Black's Mad Cap Violet were about yachting too. I will do my best to believe in your shyness if you' ll promise to try and believe in mine. I hope you' ll remember to pay some visits up in this part of the world when your time there comes to an end. With best regards, Yours very sincerely, Frank.

Dalton Hall Victoria Park 30.1.1898 Dear Mary, You never told me what to sing, so what was I to do? Well, I sang 'To Anthea' and 'I' ll Sing the songs of Araby' , thinking you might have chosen those. Was it a punishment for saying I was greedy of your letters, that you kept me waiting still longer this time? I began to wonder what terrible offence I had committed, and I almost thought of beginning this letter: Dear Miss Spence Watson. But I must be rather a nuisance, I expect,—for which I apologize. Do you remember the sweets with mottos on? I remember three very well, namely—'I can't understand you' , 'Have I offended you?' and 'Come and sit beside me' . I think I must buy some with those on, and send them at appropriate times: —especially the last. I am glad it is nice where you are, but am awfully sorry you' re so homesick. But perhaps you are feeling more at home now. How long are you staying there? How comic about the smoke! But really I hardly ever smoke during the term; only that was just at the beginning when I had a few left over from the holidays. When will you come and make some toffee in my room? Falkner and I as usual have all sorts of wonderful schemes in the air. The amount of time he and I spend in discussing his affairs (i.e. of course him and A.T.) is terrible, and I don't think it's very profitable. I have had to come round almost to your view of the case: it seems a very extraordinary situation—they seem to know one another's feelings exactly, and so choose to continue the friendship—he of course hoping for something better. Will he get it? I think I would bet on his doing so: but I expect you know more about that than I do. I expect my paper will be printed in the Friends' Quarterly Examiner, which I suppose won't be till somewhere about April. I could of course send you the manuscript if you would really like to see it. I was annoyed that there was hardly any time for discussion on it; as I wanted to hear it treated in a more practical way than I had done, by people of experience. Albert's paper was on Science Teaching, or rather its place in the School Curriculum; and a splendid thing it was I thought—so clear and racy. My leg is getting on beautifully thanks: I can manage straight forward walking all right now, and am only wearing an elastic kneecap. I'm not sure whether I dare go beyond a single sheet,—may I? Besides it has just struck twelve, so I must say goodnight. With best regards, Yours very sincerely, Frank.

Dalton Hall Victoria Park 10.II. 1898 Dear Mary, Thanks immensely for your delightful letter. I am so glad you like the Guy Mannering: and whatever do you mean about wasting money? I am sending you my paper herewith: I don't think you will find it particularly deep, but I'm afraid it's often very vague and general, too much so to be of much use. I have read your letter about fifty thousand times, to speak Griffinese; there is only one paragraph that I don't altogether enjoy, and I don't quite know what to say about that, except that if it ever was true, it is certainly not so now. Perhaps I have no heart, or perhaps I have too much sense to sigh for the moon: anyway, if every wound had as pleasant and good a case, it would be nice. I wonder if you understand that, and what you will think of me if you do. I have been wondering ever since the middle of August whether I understand it myself. I can't remember being angry on Rum, but what made it seem impossible that you could be right was that I did not see how to defend her conduct from the charge of being cruel and heartless, if it was so. But since then I have gathered from what Falkner has said, that they understand one another's positions exactly, and take the risk as it were—which explains it and makes it all right. But don't you think there must be more in her feelings than she knows herself, to make her take such a course? That is my theory—but I am getting rather out of my depth. I am writing this in the afternoon as you won't let me sit up late; my last letter to you was written later than ever, namely between twelve and two on Saturday night, as I was going to be out all Sunday. I think it is rather a nice time for writing letters—everything's quiet, and you don't get disturbed, and also you don't feel that you ought to be doing work all the time. I am glad you' re enjoying your singing lessons; I am always meaning to take a lot more myself, but practising would be difficult to manage at the Hall, and in the holidays one's never long enough in the same place. I wish I could learn some duets with you; 'Maying' for instance is a lovely thing; do you know it to sing? If not will you learn it? And I will, and then we' ll sing it some day. I will certainly sing Mandalay at Mr West's. What tremendous fun about the French! But I can't claim to be good at it; I am fairly good at reading it, but as for composition and conversation, I'm afraid I'm very little use. Still if you like to take me as I am, of course I should like doing it immensely, but only on one condition and that is that the French letters are all extra ones—it wouldn't do for them to take the place of the English ones at all. Can you write as nice ones in French as in English? Never mind about making them short; it' ll be good practice for me too. The idea of your shopping in the carriage makes me quite frightened. I wish some one would leave me fifty thousand pounds. Falkner, Gibbins and I are going to the Elijah tonight, by Halle's Orchestra and choir; and Santley is singing. I am tremendously fond of the Elijah; some of the choruses are so terrific, and there's such a splendid dramatic interest about the whole—a thing that is quite absent of course from the Messiah for instance. I got my bundle of Arnold's letters back today from Gateshead, with a letter from your sister; she says she is over head and ears with preparations, and is also learning housekeeping. I'm sure you ought to be at home teaching her. By the bye, I want your advice very much on two things. I should like to give her a wedding present—do you think she would like it or not? I think myself she would, but am not quite sure. And secondly, if so, can you suggest anything at all likely? I think I should choose a book as the most appropriate present from me, but I haven't thought of anything yet, and of course I don't know what she's got. Your letter was 'rather a nice one' , and if it was stupid, I hope you' ll always and often write stupid letters. I'm sorry I imagined such 'absurd thing' , but one does got taken that way sometimes. Besides, 'only 2 or 3 weeks' ! Of course it will be terrible for you to come back to Manchester, much more to visit the Hall, yet awhile. I'm afraid the tea party Falkner and I used to plan is still in the distance; indeed it can never be what it was to have been. Did you ever hear of the things Arnold said about it in the early days of his delirium? It is awfully nice having that photograph of him; I've got it on my mantelpiece. I bought one of the cabinets too, but it is of course nothing like as good. A good many were bought in the Hall I fancy. I think you will get the Griffin in a very few days now: mind and be present in the spirit at Mr West's on Saturday week, and 'come and sit beside me' . Do you remember how we used to keep each other's feet warm in the cabin? With best regards, Yours very sincerely, Frank

Dalton Hall 27.III.1898 Ma chère Marie Thank you so much for your letter, with the interesting account of the wedding: it was very good of you to write to me then. Parts of it grieved me greatly, especially the part crossed out, which I read in spite of you: it is dreadful for you to think like that, when there are so many to love you, some too who love you better than anything else in the world. I hardly like to speak of it again, but I still think that a few days with us in Wensleydale would do you a lot of good and that you would enjoy it too when it came to the point. I have been quite in the dumps lately, what with your not coming with us at Easter, and then too I hear (thought I don't believe it) that you won't be at York at Whitsuntide—in fact I'm beginning to think I shall never see you again. Some times even I get worse and think you wouldn't mind if I didn't. Won't you run over for Easter Sunday any way? I am sorry to have dropped into politeness; it occurred to me that other was cheeky. I might retort, why do you always wind up so politely, 'coldly' in fact? I will send back your French letters only on condition you send them back to me again: I'm sorry you tore it up—I really wanted it. Yes, I think I shall speak to you if we ever do meet: in fact I back up rational dress immensely. You must have yourself photographed in it, and send me one. I' ll send you our Wensleydale address next letter. Tomorrow I'm going home. Almost everybody has gone now, and we are having a nice quiet day or two. Falkner and I have had Dora Brockbank and Alice Lunt to tea this evening, and have had quite a jolly time. Then we saw them home, and spent the evening at the Lunts: they are both great sport. Falkner has been considerably bowled over by his last letter from Liverpool, which seems to have been 'horrid' . He's hardly done any work since; in fact plays billiards and smokes cigarettes all day, and talks to me all night. The other day we had a bit of a Griffin party at the theatre—Miss Scott, Mr Fowler, Joe and I went to see the Second Part of Henry IV, enjoyed it immensely. Nearly all the chief parts were very good: especially Falstaff, Justice Shallow, and Mistress Quickly. How is the Cookery Examination getting on? Please send me a copy of it; I should be most interested. Is it written, or is there practical work to be done? When will you give me some lessons in the subject? I've been getting a jolly lot of reading done this last week, as a lot of my work had stopped because of the College exams. I've managed among other things to finish that philosophy book that I began in the cabin of the Griffin: do you remember? I think it was just before a game of pounce patience with you, and I'm afraid I didn't take in much of what I was reading. I am quite hoping to be able to play cricket all right next term: that will be jolly. The other day I got into football clothes for the photo of the team: I felt tremendously tempted to go and play—it made one feel quite young again, instead an ancient party too old for active exercise, as I've generally been feeling like lately. Another thing that makes me feel horribly old is to hear of fellows that I've taught getting engaged. I am sending you a programme of our Social of a week or so ago. It was a tremendous success: Mr Neild was here and several old students whom it was very jolly to see again. Schwann and I sang 'Friendship' , which was liked very much I think: he wanted to change all the 'he's' and 'his' es' to 'she's' and 'her's' , but I wouldn't. He is a very interesting case, being at present over head and ears in love: Falkner and I see a good deal of him, Falkner sympathizing with him, and I lecturing him. But it is very amusing, or would be if it wasn't rather perilous. My lecture came off all right I think at the Institute here, though some did say they hadn't understood a word—I believe they meant it for the highest praise. Mr Neild made an amusing speech, in which he said that when he was a small boy, he imagined the soul was shaped like one of those lard bags that hang in the shops. I think I used to have much the same idea. Falkner is just now deep in my David Copperfield—you may imagine what drew him to that one particularly. I tell him the finest character in the book is Betsy Fastwood, and next to her comes the Dora episode: but I'm afraid he won't agree with me. I don't a bit like this letter, but perhaps there's no harm in sending it. And now I must say good night (I always think of the Griffin when I write this),—it is awfully late. With best regards, I am yours very sincerely, Frank.

Dalton Hall, 12.V.1898 P.S. I was so sorry to hear a few days ago of your Mother's illness: I do hope she is better. P.P.S. Don't read this letter in public. My dear Mary, As you seem to have signed the pledge against writing to me, I suppose the only thing to do for comfort is to write to you instead. Why are you so cruel? Don't you know how I long for letters from you, and how I love them when they come? And my hopes rise half a dozen times a day, only to leave me more forlorn. Ah! Mary! I have waited long enough,—don't you know how I love you with my whole heart and soul, and how there is only one thing in the world for me and that is your love and the right to love you as I long to. How can I sit down and write all this on paper? How cold and weak it looks! How can I tell how I feel, how I long for you always, how I treasure the thought of all the times we have been together, and fancy many many more in the future. Dearest Mary, there is no one else in the world for me but you,—there is nothing else worth having, unless you will be my comrade always. And yet I feel as I write that, how little right I have to ask it, how utterly unworthy I am to dream of anything so beautiful,—how can I dare to put myself beside you? and ask for your own sweet self? I have no right, I am often miserable at thinking how utterly unfit I am—but I love you Mary, and must tell you, and leave my fate to you. Can you ever care for me a little bit? I would spend my life in loving you and serving you. Do you know how I have thought of you and dreamed of you for months and months? I have lived on the memories of our times together, and the dreams of meeting you again. And then at Easter it suddenly came true—and what a funny time we had! And yet to me it was divine, short and hindered as it was—and some moments in it I have been living through in fancy over and over again. But I have felt ever since that I could not be content with fencing with the subject much more—and now my heart has opened itself to you. It is yours Mary absolutely. I never meant when I began this letter to tell you all this yet: but just sat down, miserable at not hearing from you, and longing to talk to you, and wrote. But I found I must say it: the thought of settling down to proper cold letters again was making me mad. I felt I must risk everything and tell you and hope for the great reward. Oh Mary! The doubt is terrible; and after all what business I have to hope or why you should reward me I don't know. But I do hope: it is so sweet to think of being able to love openly and fully, and of having such a treasure as your love, how can I help but hope? And yet how can I dare to? Oh Mary, I wish I could make you understand how I long to see your face again, and hold your hand, as I did on Prudhoe platform: and I dare even to think of 'passing the Rubicon' : May I? The thought of the future is only bearable, Mary, if I can hope for your sweet companionship, then it is lovely. Otherwise it is a horrid blank. Oh! How feeble all these words are to tell you of it all, and how incoherent and clumsy they seem. But you will believe that they are genuine: you will not tell me I exaggerate: I do mean every word I say,—and far more, if anyone ever meant anything. Oh! If I could hold your hand, and look into your own dear eyes, I might tell you something of my love—it is all I can give you Mary, and it is yours now every bit of it. And what a prize I am asking in return! Your love and your self! Really it is very cheeky of me: but I'm not often cheeky you know, so you must let me off this once. Don't tell me my hopes are absurd: don't even say 'soon' and run out of the room, but tell me now that you' re going to take pity on me, that I may come and tell my story into your ears, and hear the best news I ever want to hear, from your own lips: Oh Mary it would seem too good to be true; the thought almost terrifies me, I seem to have deserved no such happiness, nor to be fit to think of serving you even afar off. But 'My true love hath my heart' and what can I do but tell her, and hope she will believe and understand, though it is only feebly put down here: and hope too that my dreams and fancies may really come true. There is much more that I ought to say, that you have a right to ask me to say. But I cannot write more till I know my sentence. Yet you will believe what I have said, and may I hope that Mary will even grant me a little of her love, and a hope that the greatest treasure in the world may be mine. Dearest Mary, don't think this letter silly—I cannot pause to think of words and phrases, but it is from my heart. How can I live till I hear? But whatever you may think or say, I shall always be yours, Frank Dalton Hall, 15.V.1898 Dear Mary, In spite of your postscript I cannot let your letter go without a few words of reply, and one petition. I need not say how absolutely wretched it has made me; and yet, though its news was so terrible,—if anything could have made me love you more, your letter would have done—it was such a beautiful one, though so cruel. But Mary, please, please do not add to my pain by blaming yourself: indeed you must not, you have no cause to. And do you think I would rather have never loved you? Why, it is the only bit of happiness I have left. I suppose I cannot complain that you think me a fickle changeable person: and yet though it may seem so, I do not believe I am. Indeed I know that what I told you was no passing feeling, and some day you may perhaps believe me. There is only one way in which your greatest wish can come about, and that is by your filling the place yourself: that is my dearest, my only, and my everlasting wish. I am utterly stricken to think of having given you so much sorrow—and I will do anything you ask—if you like, we will go on writing just as before—it can be done: or if you prefer, we will break utterly. If it is any comfort to you, you may feel sure that to serve you in any way however small, will always be my greatest indeed my only happiness, whether on occasions when we meet, as we shall have to, or by avoiding you if that would please you best. As to telling your Father and Mother, you will of course do what you feel to be best: I cannot and do not object in the least. But enough of all this—I have one thing to beg for, Mary, and if you have any pity or feeling for me at all, you will grant it. It is that I may see you. A thing like this cannot be settled in a couple of letters. Let us meet one another, Mary. I am perfectly certain it will be best for both of us. It is a small thing to ask in a matter of this kind. Your first impulse will be to refuse; but do not obey it—it is my one little request and you may trust me not to give you needless pain. Let us go for instance to Prudhoe—I could get up from here and have just the same time there that I had before. It is because I think we should understand one another better, and it would save unhappiness, that I ask this: do not refuse it me, Mary. If it cannot be managed before, couldn't we have Whitmonday afternoon at York, or Tuesday? but that is a very long time to wait. Dearest Mary, if I may call you so once more, grant this one wish of mine: believe me mine is no passing feeling as you suppose—it is a question of the greatest happiness and privilege and duty throughout life, or a life—bearable I suppose—but with all the best gone from it. And it is this best that has been, and is still my dearest wish and hope. May I say again that neither I nor yourself nor anyone else have any right or cause to reproach you in the very least for anything you have done. Your friendship in the past and my own true and lasting love are my only treasures left. Ever yours, Frank

Dalton Hall 18.V.1898 Dear Mary, Your letter was very kind, and it is a great comfort to think of being able to see and talk to you. How would it be for you to come to Manchester from London? That would be all right as you have told your sister—I could see you there. But if that doesn't suit, I will come to Prudhoe the first day after you get back. I can manage to be free any day next week except Thursday, or any day this week. I don't know of any reason why Arnold should have said what he did in his illness. Ah Mary, the help I want is help to win your love, and that no one can give me, I'm afraid. Ever yours, Frank. Dear Mary, there is no question of forgiveness; but it is more awful than I can tell you to have all one's happy memories and all happy hopes cut off at one stroke—but indeed they are not quite cut off yet. I cannot help hoping even yet that our happy friendship may some day grow to something far dearer. Forgive me for this: it is perhaps utter madness—but though so very faint and often dead, it is very sweet. I shall hope then to see you in a few days.

Dalton Hall I.XII.1898 Dear Mary, It was such a refreshing delight to get a letter from you again after all these weary months: especially a nice chummy letter that made one feel we were not utterly parted. I will never believe that with such memories of joy and sorrow we can become strangers or mere acquaintances: it seems madness to dream of it. I should like very much indeed to see Arnold's letters to you—any that you think I might see: I am quite sure they would all interest me. I delivered your message to Gill and Gibbins: we are all glad if any sympathy we have given has helped at all during this time. When I read some parts of your letter I long to be able to do some little thing to comfort you—and I may not! Oh sometimes it makes me almost mad. It is so lovely to be able to sit down and talk to you again: I wonder if you have any idea what this six months has been to me—a time of utter loneliness, when everything seemed purposeless, and all zest was gone from life. If I had followed your advice and forgotten, I should have had nothing left: but as it is, I have had one treasure and have kept it bright. If it is ever anything to you, Mary, that there is someone whose best hope is to be able to make you happy in any way however small, and who longs always to give his life to it, you must remember it, and let me serve you. Confess, Mary, that my love is not quite as flimsy a thing as you fancied: how could it be when it is all given to one who to me is all loveliness and love, all the dreadful faults she talks about and everything. Forgive me Mary—I have been miserably silent all this time, and have felt that you never really understood what I felt. But now I will be very 'sensible' , and will begin at the beginning. First I want to thank you again properly for the Songs of the North, which have been a beautiful keepsake: but it was dreadful to send it without a word—I thought of sending it back. Also you really must come soon and write in it. And do you know, it's nearly all about 'M' hairi' . And then for your lovely card in September: it was very sweet of you to remember me then—it came like the shadow of a great rock in a weary land. I read the diary very carefully every day in August, but it is getting rather dim in parts, not being in ink like yours. You have never seen it since it had its additions have you? I am actually playing football again, much to my own surprise. But by playing with a strong leather support on the knee, and beginning very gradually, I have lasted so far. I was over at York playing an Old Scholars Match not long ago and stayed the night. And at the meeting house had the treat of hearing Ruth sing: her song Bonny Bobby somebody was running in my head for long afterwards. Also Mrs Richardson she sang 'Went thou in the cauld blast' , which carried me back to the drawing room at Bensham. I hope you have been doing plenty of singing lately. Do you know I am going as a master to Bootham after Easter? I shall be very sorry to leave Manchester, but glad for many things to get into a school again, though the life won't be quite so free. Faulkner is in rather a bad way: what is to be done with him? He says he has had enough of these alternations of hope and depression, and is going to drop all writing for a few months. I don't know whether the mood will last, but that is what it is at present. A.J. is coming over to help at our stall at the Bazaar: a very funny thing for her to do, don't you think? I hear you are going to make a cake: what kind will it be? Chocolate? How very naughty to write letters at such a time of night: though there is certainly something to be said for it. It is at present half past twelve—quite like old times. Talking of old times, I hope this doesn't smell of smoke—Jeanie actually gave me a pipe when we were in Devonshire, and I occasionally use it. You' ll have to write and scold her. Don't you think you can get over to Manchester before long, Mary? It would be so delicious to see you again, and a good talk is better than twenty letters. And another thing is, mayn't I have a real proper photograph, Mary? I think I've written a selfish enough letter this time at any rate. Forgive me if I have said anything to give you pain: and forgive me too for taking for granted that you would care about our writing to one another again: perhaps I am quite wrong and am only troubling you—if so, you must blame my foolish hopes. I will promise utter obedience in future—I will be as sensible as you like: but will only consent to be quite silent, if you can honestly tell me that it will make you happier. May I not be allowed to judge about my own side of the question? And whose happiness has the arrangement for this six months increased? If your, Mary, we will continue it; but surely not otherwise— Ever yours, Frank. Forgive this selfish letter: I have read your sad one over and over again, and feel as utterly unable to help as I should like. To me the only real consoling power seems to be found in the service of others, and all religious comfort seems to me to find reality there. But what where the sorrow is that one may not serve as one would love to? Do you know Whittier's 'To my friend on the death of his sister' ? I expect you do. I think it is one of the most beautiful things of the kind ever read.

Dalton Hall Victoria Park 5.XII.1898 Dear Mary, I got your delightful letter with its still more delightful news in the middle of the Social. There is much I want to say about it, but the thing is to meet as soon as we can, and alone! Can you spare an afternoon this week? I would suggest that I should meet you by the trams by Fallowfield station and that we should then go somewhere together—the Art gallery or my room or somewhere: or if you think it would be more correct, I will call for you at Clifton Avenue. I don't know whether you will think this an unsuitable suggestion, but I see no other way of being alone together. And to meet when others are there will be much easier afterwards. It is dreadful to think of your having been two days in Manchester—and I haven't seen you. If you will do this, Mary, I will be by F. station at two tomorrow (Tuesday), or 2.30 on Wednesday. I enclose a note to Mrs Weiss telling her what I am proposing. She will not I think object if you wish it: she promised me she would not interfere again. If neither time suits, then Friday at 3.0 would be the next. But I am longing so to see you—that would be a dreadful age. Ever yours, Frank. 'In spite of all you say' , Mary, 'it has 'not' been so' .

Friends Summer School Birmingham Sept 4th to 5th 1899 Thursday 6.20 pm

My dear love, I am hungry, and tired and sleepy, but I have a feeling that I have not put some parts of what I think quite as fully or seriously as I should like. Perhaps it will be more possible to be serious in a letter. Is it worth while saying anything about one's early loves? Are you serious in caring about it? Why do I speak of them as being imaginary and more or less sham? Is it because they are over and gone, and shall I say the same of this some day? It is nothing of the kind: it is because then I loved a purely imaginary being, not the reality—for I didn't know it: do you suppose I ever had an intimacy and comradeship so near and open as yours before—for that is what it is, say what you like. Of course not. My love for you is the first that has been based on knowledge, it is the first I have ever uttered, it is the only one that has really saturated my life—is that not enough for you, Mary? That is why I know it will last. I think you don't understand what the giving of his heart to a girl can be to a young man. There is no influence conceivable so strong as this for keeping him straight and true,—he must long to be worthy of her. Alas! would that he was in this case! It is the one comfort I have—and it is a gloomy one indeed—that things are better this way perhaps for I am so wholly unworthy. You ask me, sweetheart, for a list of your faults; and wonder how I can love you. I don't know whether I can answer that. What can I say but that to me all that is sweet and lovely; I have a boundless admiration for your genuineness and sincerity—it is not common in women, or so I fancy; and the more I think of it, the more important and the more delightful does this utter absence of sham seem: what is greater than truth? And this is truth of soul. But I cannot analyze you, Mary—it is your whole dear self that I love. You are my ideal of a sweet and gentle and sympathetic and independent woman. I don't mean to flatter, and I don't mean that I think you are perfection: but I hear you say 'Ah this all shows you don't know me?' But that is wrong—It is the one who sees the best that truly knows; the lover's picture is not imaginary—it has the deepest truth in it by far. I wonder if you understand how a man looks upon the question of married or single life: you seem to look only at the responsibilities and worries of the former—not at all at the self-centeredness and isolation of the latter. To me the pictures are these: on the one side—a life solitary and alone in all the deepest things of life, no one who cares for you to speak of, no one at any rate to whom you are the first thought, no one to cherish and care for yourself—a life shorn of its brightness, and of all, or much, that can make the fight possible and even splendid. On the other hand, a life of true comradeship and union between two lovers—each feeling that with the other life is worth living, and work is worth doing, and some success is possible. There is a dreadful sense of antagonism in so many married relationships one meets with—to me this seems awful. But a real loving partnership seems the only life worth dreaming of. And forgive me for saying so, if you don't like it—but I feel often that you and I are not far from this state—one of great interest in all one another's concerns, one of utter freedom, of close sympathy: what do we talk about except one another? Why do you care what I think about things and what I read, and so on—Is it because you are at all in my state,—who live (or try to) my whole life, as it were, in your sight? How do I know that I am really and truly in love with you? Because the thought of you is always close to me, even in the busiest times: because I willingly let all engagements and all other intercourse go to the dickens—if I can get one touch of your hand: because at your side I am happy;—when you are away, there is always a blank. Not that I am constantly and permanently feeling some tremendous emotion. Perhaps I am unimaginative and phlegmatic—I don't know—but I know my heart is steadfastly yours and knows no other mistress. I have much, sweetheart, to ask your forgiveness for—I get irritated and impatient I know, and unkind, and not much of a lover I expect—but you must believe me when I tell you that my heart is never other than full of love and tenderness for you, and of longing to do anything for your happiness, and to share and help you in your sorrows. There is no day that I do not think of you, but on the day you mentioned I will think of you very specially whatever happens, and if all the thought and sympathy I shall give you then, is some little comfort and help, you know that you will have it, Mary, in abundance— Forgive this letter— Ever, Mary, best and dearest, yours, Frank

Bootham School York 20.IX.1899

My dearest Mary, What can I say in reply to your dear letter? I'm not sure by the bye whether I ought to be replying to it at all. But I promise it shall be a very 'sensible' one, if possible. Your letter was a dear one all the same, full of laughing and crying, like our time at Birmingham—like most of our times together, for that matter. But what I want—I'm very greedy in these things—is a really long one every other day at least, and with a little of Mary's love in it too. Well, I think there is some in all her letters really, but what would I not give for her to tell it? One of these days she will have to make up for all that has been owing the last year or two. But this was going to be quite sensible: so I must begin again. Your letter wasn't half enough about yourself: I feel as though I had been spending all the time lately fighting so to speak, and hadn't really heard or talked a bit about you. I want to know how the house cleaning is getting on; what you are reading; whether you are obeying orders (as I always do) as regards playing the piano, and are going to play regularly in public; whether Tommy grinned when you came home, and whether he has bitten any boys lately. (I sometimes wonder if we should quarrel on the question of keeping a cat!) Also I want to know what poetry you are learning, and what the passage from Keats was. I shall probably have to take (I half promised to) the Sunday Evening Reading in the Meeting House some time this term or next. What shall I talk about? I have an idea of writing a paper on 'Religion from a boy's point of view' —but I'm afraid I haven't got much further than the subject yet. But I often think boys at school must get horribly mystified as to the connection of all the religious talk they hear, with their own lives. I'm sure I did and do. Oh the Sunday I was at home at Ackworth (before the Summer School), Albert was there, and gave the school such a splendid talk at the evening reading on privileges and responsibilities—I seldom heard any thing of the kind better. He wound up with that grand old story about Henry IV of France and Crillon—'Go and hang yourself, Brave Crillon, we have won the fight, and you were not there' . I am writing this with an Iona penholder that Jeanie gave me at Oban. On the 12th she sent me two ties, which I hope you will like: and Mary wouldn't give me anything, even though I asked for it!—she really is an obstinate thing, but I'm so much the reverse, that it' ll be all right. I didn't know before that the Old Maid Castles in the air were pleasant ones: I thought you resigned yourself to them because you thought you were cut out for an old maid by nature; and now that you find you aren't, why they must go. I am wondering what the point is exactly in not seeing me, and in waiting. I will put up with waiting, Mary, if we may see a good deal of one another. But as for complete separation I see neither rhyme nor reason in it. What is the good of seeing if you can't forget and cease to care,—for that is what it comes to. Supposing, when we are not together, there do come hard unfeeling sort of times when one hardly seems to care for anything or anybody—well, that proves nothing: that is not your real self—the real one is the one that always gets the upper hand again, the lasting one, the one that feels strongly—that is the one to follow. I wonder if all this touches your case, does it, Mary? You don't know how my heart aches, sweetheart, to help you across the abyss. Isn't it conceited of me to think that that will bring you happiness? I think when I have won Mary, I shall be quite unbearable. I think you had better come to York for a few weeks or months—and then if you get quite sick of me,—why, I' ll go to New Zealand or something of that sort, and the matter will be settled. How jolly it will be some day for us to look back out of a region of serenity and happiness, upon these stormy times. Ever, Mary dearest, Your lover, Frank. p.s. I'm sorry about changing the name, but don't see what can be done. p.p.s. I have just been buying 'Frankadillo' : can you tell me the composer and keys and ranges of 'The Milkmaid' ? I tried to get it and they showed me two settings of it, and neither the right one!

Bootham School York 24.IX.1899 Dear Mary, I wonder if I have sufficiently collected myself after your letter to reply. Any way I will try, and there shall be no love or forgiveness in it—it shall be grim argument—not that there is any use in further discussion after your ultimatum.—but—well, a man likes to have the last word you know. I still consider that your coming to York for three months and our seeing as much of one another as possible, followed if you like by a few months' separation, would be the better plan both from your point of view and mine. Unless of course the object is to see if you can't forget me—in which case why not make sure and call it twenty years instead. Here is a maiden in a difficult position of loving and not loving—an unhappy sight—it is not that she is not very happy when she's with him, not that she does not miss him when he's away (it seems incredible, but she says so)—but it is that when she's away from him, all the difficulties and worries come to her mind, the misgivings and the shrinking gets the upper hand. What then? So they do, I am certain, in most people at times, even the most ardent. But life is not to be passed away from him, but with him. Every one has times of misgiving and shrinking from such a tremendous step, which comes when the loved one is not there. What is to be done? Why, they are to be smashed utterly, and kicked out. Is the remedy utter separation for a while? Surely not, it is daily intercourse, so that there shall not be passing times of dreamland at long intervals, but lives that intertwine more and more—which will cease to fear the humdrum of married life, for the 'happy dream' will be sure to pass into settled daily real happiness. That is my view as far as I can put it into a few words. Goodness me! What a pity we aren't living in the days when a woman was carried off by main force: I really believe that is the only treatment that will meet your case. But of course if you dread marriage so awfully as you say, there's no more to be said—and I'm afraid I shan't be much richer in two years time. And let us look at the other alternative—if you were to give an utter and emphatic refusal. You must not think that we could know ever again the intimacy of the last year or two; not, l mean, that a friendship would be impossible, but that ours has been much, so very much, more. We shouldn't go walks together by our two selves, oh dear me no! We shouldn't love to talk (or if we did, we should have to refrain) of all the times we have had together, in which all the least details have a magic of their own. Certainly not! We should talk about the weather and the crops. No more happy dreams for us—(dreams by the bye which were not happy because of passing feeling and sentiment, but because of a sense that we belonged to one another, because all our interests and thoughts and sympathies were so honed together—and that I think is a reason that will stand the test of humdrum life). Of course you would burn all my letters, and even Guy Mannering and the brooch had better be put out of sight I should think. And I—well never mind about me. Such I think is the picture that we ought to face with equanimity if we took such a step. And if we can't do it with comparative equanimity, we are taking a step which is against our deepest feelings—and why? Because when alone, the anxieties are more prominent in our minds than the love which shall over shadow them; because we can imagine ourselves falling in love with somebody else—Pooh! I can imagine any mortal thing—from committing murder to being Pope of Rome. Or is it because we think happiness consists in outward things, and not in the deepest facts of comradeship and love? Well, well, I have said my say, but you will go your own way probably. I should say don't name any period—you will only feel as tho' a decision was hanging over you. I will promise not to ask you again for a long while, and I will not feel bound by anything except my own heart. And Mary must promise to tell me of her own accord, if she changes— One thing more—there is no question of forgiveness. I should be the last person to blame any one for giving the most anxious thought to such a tremendous step. And as to anything else, your feelings being as they have been, I don't see how you could have acted otherwise—indeed it would have been wrong, for it might have spoilt our future happiness. Believe me, Mary, I have never blamed you in my lightest thought. Two years is a long time! Mary will deepen all her other friendships, and form new ties perhaps, and ours will be forgotten, will they? And I—well, perhaps Mary's image in my heart and my love for her will keep me from growing quite selfish and crusty. Do not dream that I shall forget, sweetheart. Ever yours, Frank. Many, many thanks for your long letter and the hymn. There's no hurry about the Milkmaid or the notes. It is such a great grief to me, dearest, that I seem to have brought so little but perturbation and unhappiness into your life! I'm so glad about the music.

Bootham School York 12.X.1899

Dear Mary, I'm not sure whether letters are still legitimate, or whether, after the ultimatum negotiations are broken off. But this is just by way of returning the notebook—for which many thanks. They are very good notes, though sometimes too brief to be understandable by one who didn't hear the lectures. I made one correction. Best thanks also for something else—what sport! Mary's given in, for once—but daren't own it! The idea of your being like Dora is very comic. Didn't you know I'd chosen you because you were such a good cook? I think you are a mixture of Elizabeth Bennet, Catriona, Bella Wilfer, Little Dorrit and Mary Garth:—all their good points that is; I don't think you' re mercenary, as Bella was. I had chocolate and a walk with Bertha last night, which was good for me spiritually. I think you are a riddle—one' ll need a life time to work you out—so it's just as well that I'm to have it (in two years time?) Don't imagine, if I say nothing more, that I am convinced. I don't see any reason why a party should fall in love with some one she never sees or speaks to. As to coming to York, if it is best, it ought to be managed. Observe my selfishness—but when a man is fighting for his life, he may be selfish. Shall we make a bargain? I' ll promise not to think you so good, if you' ll promise not to think me so good—that' ll settle it. All the same, Mary is and always will be to me the best and sweetest and dearest and loveliest, Frank.

Bootham School York II.XI.02 My dear Mary, I send herewith a just payment of my just debts. It makes one more letter for you to answer – but I' ll let you off the rest, if one of these days you will reply to the one of last June: don't you think it deserves one? I think you will. Any way don't be angry with me for anything I have done or may do, Yours ever, Frank. p.s. It was so very, very lovely to see you, dear Mary! I think if you knew what a breath of fresh air you bring to me, you would have compassion on me oftener. Bootham School York 26.XI.02 Dear Mary, I thought I must try and write you a few lines tonight,—in spite of all the good reasons there may be against it. I often think of what you asked me once at Birmingham—do you remember?—to think of you at this time of the year, and how I was rather angry and wouldn't promise. But I think you know that I always have done, and have longed to help you. I was going over again with Mrs Richardson, the other day, the events of that terrible week five years ago. But after all what one really loves to recall is Arnold himself—his truly sympathetic spirit, and his unswerving loyalty to what he thought he ought to do. Knowing him even as a pupil and a friend, I can see these qualities so clearly still, and feel them to be a good memory: for you, Mary, I can dimly see what a loving comrade he must have been to you, and what a precious possession you have been stripped off since he left us. I wonder how you find your way, or what way you find, through these mysteries. I only know that the memories of those we have lost—their images in our hearts—are treasures to be kept safe and bright, and presences that we must try and be worthy of: and that no loss or grief must hinder our playing a man's or woman's part in the world. But that is much, don't you think? Yes, and there is this too—that we may all try,—and surely you and I, Mary, among the rest—to be as Stevenson says, 'even down to the gates of death, loyal and loving one to another.' Forgive my writing—but the time is so short since I held my own brother's hand for the last time and heard his last wishes for me, that I thought I should like a little talk with you about these things. I wonder if I shall see your father at Leeds or Manchester on the Peace Deputation visits: I haven't had an invitation from Newcastle yet!! Yours ever, Frank.

Bootham School York 2.VI.03 My dear Mary, I cannot keep myself from writing to you to say what happiness you let me have for a while yesterday—short and interrupted tho' it was. It was so delicious and refreshing to hear your dear voice again, and hold your hand. Don't let it be so long again before you give me a little light in the darkness. I am keeping the present yet a while after all; so you' ll have to wait a bit. When I receive your diary—which I want to see very very much—I' ll send you mine: but you' d find it very prosaic, I'm sure. I'm better at writing other people's diaries than my own—and even then only with assistance, and in the most comfortable of circumstances. I have been taking in hand lately a number of Albert's papers with a view to printing them in a small volume for private circulation: I wonder if you would like one when they come out: they are educational and religious mostly. It is uncommonly difficult to settle to humdrum work this morning—especially for me—hence (perhaps) this letter, while I have a little time free. I was interested in your learning Latin—tho' I think (I had to stop here—and I can't for the life of me remember how sentence was going on!). Why Latin I wonder? Why not Greek? or Psychology? I recommend that. I live in permanent admiration of your wonderous energy. I feel as though I never succeeded in getting anything done myself: and the number of things to do grows day by day—books to read, methods of teaching to work up or think about, one thing after another—and where is the time? I am hoping to get over to Manchester to the Old Students' Gathering on the 20th; and shall see Falkner and Agnes in their new united bliss—I am glad to hear he is 'splendid' . But the modern education, we understood last night, turns out 'incomparable old maids' ! It will be a grim failure if it does nothing better than that, won't it? I had ten thousand things to say yesterday, but want of time, or of ease and peace, (or perhaps it was shyness!) prevented: and I haven't said many even now— Yours ever, Mary, Frank.

Bootham School 15.VI. [no year or envelope, but it appears to fit in here] My dearest Mary, I have only a minute or two before post time, having only just about heard of your having gone home—but I must send a word or two. I would have come to the Station, only was on duty at 4.0 for the rest of the day. I have been in a state of mingled perplexity and joy, all day: joy because I think you are going to make me happy—but I have an uneasy impression from your words yesterday, that it feels to you like something mainly dreadful and that you are making a sacrifice for my sake. You know I hope that I long for your happiness too much to think of your doing that. But it isn't so really—I know it isn't—it is natural enough just before the step is taken to think over all the changes and responsibilities. Are you convinced—Mary, that I wasn't a bit shocked! I do believe very strongly in free discussion of such things at the outset. And do believe, Mary, that I long for your happiness, and have a boundless reverence for you, as well as love. Well! Mary—it was rather horrid to part having had so little but argument—but when we meet again soon it will be different—we shall be starting on the more perfect comradeship of lovers. Ah sweetheart! It seems too good to be true. It will be no more endless and fruitless discussions—but loving and learning to love more and more, and growing more closely bound together. And for me to try more than ever to be worthy of your own sweet self—and now good night. You know you have all my best love, my own dearest Mary, Yours always and always, Frank.

[Undated letter, but fairly obviously August 1903] My own dear Sweetheart, We shall be so late into Ackworth that I shall scarcely catch the post even for a little note to thee. Hence this scrap in the train. I ran off to catch my train, remembered my bag on the platform, couldn't find it, scrambled into my train as it was going, and found the bag in the van at York! Some kind porter. Did thou have a comfortable journey? and art thou going to have a good night undisturbed by toothache or any other trouble? I wish I was holding thy dear hand now, and could be with thee to face the formidable things in store—I feel as happy as seventeen kings, and prouder than any— Thine forever and ever, Mary dearest, Frank.

Bainbridge 27.VIII. [no year] My dearest comrade, I am lying on my bed—at about 10.45—and in my usual rather cowardly way, am going to write what I have not succeeded in saying. What was I to say this afternoon? I feel that perhaps I did not denounce you as I ought: but then how can I tell your blameworthiness? I do not imagine that you did it deliberately, then was it just a case of not knowing your own mind? and if so, ought you to have known it, or ought you to have acted differently at some point? I cannot tell these things, but if you feel you have done wrong, I will not make light of it: let us only hope it will not bring more suffering than can be helped—and also of course make sure that there is no doubt left now. That is of course assuming that there is no doubt—is that correct? I wonder why you went part way and then stopped. Did you think you loved him? and find you didn't? But this afternoon I felt only drawn to assure you of my own unalterable love. If you have fallen from your best, Mary dear, I will grieve with you: but you are still to me what you always have been and will be, and my hopes and purposes are what they have always been. And now I'm going to lecture you—tentatively and hypothetically at any rate. You suggest sometimes that you have no work in the world—nothing that you do or can do well. Now are you sure that it might not be your duty—your place in the world—to perform the great functions of the head of a family? I know you to be well filled for it in many, many ways, and I want to put it to you whether you are shirking this for any reasons that are not good and brave. I am not judging you, but wish to put the question to you—because I long for your filling the best place possible, and because I know how your simplicity and truth and sympathy fit you for it, not to mention more practical everyday capacities. This sounds as though I meant it was your duty to marry me: but you will take it as it is really meant, and forgive it if it is out of place. As regards you and me,—please never again talk any rubbish about my marrying someone else—it will never be. And surely you didn't think I should never ask you again—it is years since we talked about it, and changes do come into feelings, even without provocation. I hold—as I have said before—that when two people love best to talk over and over again of the treasures of their mutual memories, when they love to unbosom themselves utterly to one another,—as we do Mary,—they do love one another—and to deny it is madness. I want no better love than such things prove. But I am not going to harass you now: I have given you pain enough in the past, Heaven knows, where I only longed to give help and happiness. But when you told me such things as this trouble, I could not help trying to convince you again of my unchanged love—in which you have so little faith. If you will not have it, then I must give what I may, and get what I can—for the present: but all the same I shall have a vision (because I can't help it) of something better—and there's no law against asking again, nor against changing your mind,—so there, madam! The fact is you' re frightened you wouldn't be 'boss of the show' ,—but I expect you would you know. Yours always, Frank

Letter from Frank to Dr Spence WatsonBentinck Villa Ackworth, Nr Pontefract 31.VIII.1903 Dear Dr Spence Watson, I am writing to ask you for the best gift that you could give me: and I feel how little I deserve it. I don't know whether Mary will have told you, but my love for her which tried and failed before has won the victory at last, and she has said that I might write to you at once to ask for Mrs Spence Watson's and your approval. I know very, very well how much it is that I have asked from her, and how much I am asking from you: and I am afraid that some things I have done in the course of a long campaign may not have been approved by you. I have only one excuse—that I have loved her all the time with all my heart; and now more than ever, if that is possible. I wish I was more worthy of her, to ask for such a prize and treasure—but we love one another, and I think that will keep us happy—any way I will try my best to serve her in all things. So I am hoping that you will grant me this great gift. Mary will I know be longing for your help and approval—she feels she is making a great venture and needs all her courage, especially now. May I hope then that you will give us your blessing, and that we may call ourselves engaged,—as we are in heart? I don't know whether you would like me to speak here of more mundane matters. Since I spoke to Mrs Spence Watson three years ago, my place at Bootham has improved, and this next year I shall be in a more responsible position—but of course there is no great substantial change. I wish that I could offer Mary an easier and more comfortable position—but that can't be helped—and I think we shall manage. I shall be glad to tell you anything else if you wish, and to come and see you about it, if that would be best—I am free just at present to do anything at a moment's notice. I wish I could tell you better what I feel about it all—but perhaps you will understand from what I have written, and perhaps Mary will help me out where I have failed. So may I leave it with you thus? With kindest regards to Mrs Spence Watson and yourself, I am yours very sincerely, F.E.Pollard.

Bensham Grove Gateshead-on-Tyne I.IX.1903 Dearest, I was so glad to get thy note this morning, for I had begun to feel as if it was all a dream, and I need all the help thou canst give me. I told Mother almost directly I got home, and then I went to the dentist's and he unpicked the stopping of my tooth and put in a new temporary one which has given me great relief. When I got home again I told Ruth, who was very sweet and kind and I believe pleased, but Mother would not let Father know till this morning, in case he had a bad night. We had some people to dinner, as Sir Robert and Lady Ball are staying with us (their eldest son is going to marry Olga Sturge to-morrow) so I felt tired when I went to bed, but quite happy, till I woke in the early morning, and could not sleep any more, wondering if I was doing right. Oh, Frank dear, I do hope I' ll be able to make thee happy. I'm so afraid I won't. You must promise if you ever have the slightest doubt, to draw back before it is too late. I'm writing in bed which I hope accounts for the bad writing. Father and Mother were in such a state about my cough, that I stayed in bed to please them—please don't imagine I feel ill, for I don't. Father came to see me after breakfast, very much surprised; he never says much, but told me 'Love in a hut with water and a crust, is, Lord forgive me, cinders, ashes, dust' , at which I was angry; he said he'd always heard you were a very good fellow, and I shan't tell you what I replied, but I told him he'd soon learn to love you, and you him. Could you come here for the week-end? (longer if you can). You might meet us on our way back from Birmingham.... [rest of letter not there—page torn off either purposely and accidentally]

Ackworth, 2.IX 1903 My dear Love I wonder if thou has any idea how delicious thy letter was to me: it is the first taste I have had, Mary, and was very, very sweet—whatever better things may be to come. I am glad thou 'would like to see me again soon' : and I will come on Saturday if that suits—and will meet you as thou suggests if I know your times. I did not tell any one till I got thy letter this morning,—then I told Mother and Jeanie and Will. Mother was very delighted (as she ought to be): will thou write to her? Perhaps Jeanie will be writing. I don't know. I won't tell anyone else (tho' it is a great effort) till thou says I may. I wrote to Mrs H.R. this afternoon, but just thanked them very, very much for their kindness—and said I should always be grateful. Would they understand that? I feel in such a mixture of excitement and happiness and solemnity—it is a serious thing, sweetheart, to have the treasure of thy self to guard for one's very own: and how I wish I was worthier of it! (n.b. I' ll give the promise thou asks, with a light heart—what a thing for thee to say! How can I give thee more faith?) I think my letter to thy father was the most difficult I ever wrote: and I wasn't a bit satisfied with it—but perhaps it didn't matter really. Did thou mention to them the Northallerton plan, I wonder? It makes me laugh to think of Northallerton platform as the scene of victory: I'm not at all sure how it would have gone, if my train hadn't happily been late. I think I must write to Philip Burtt and thank him. Yes, the bike was all right. Jeanie and I went a bit of a ride yesterday afternoon. Today I have been looking through a great lot of Greek photos taken by Argonaut people on our Easter tour and choosing a lot both for prints and slides. I do hope thy cough is better—and that the Birmingham expedition will not do it any harm. Did the comfortable seat by the river make it worse? I will write to G.H.M. to morrow if I can produce a letter that will do. I'm glad thou wrote to him at once. Poor fellow! he will have a bad time. I haven't left time for this letter—indeed it doesn't reckon one at all. I thought perhaps thou would like to see this that I wrote in the spring. I wonder what thou has been wearing to day. I haven't any clothes to come in on Saturday: isn't that serious? And now I must rush to the post. Mind and give me a good account of the conference! My own sweetheart, try and believe in it all: it isn't a dream—or if it is it's going to last for ever. Art thou happy? I am, except that thou art not here beside me. Thine, Frank.

Ackworth 4.IX.1903 Dearest, I got thy lovely letter this afternoon: and parts of it made me laugh with happiness. Why art thou so sure that Mabel will be astonished? I wonder—I'm not certain. Since thy letter came at about 4 o' clock—we have had an early tea, and Will has gone away. It has been so jolly having him here: we have seen so little of him the last few years. Our two nephews came along from the school to escort him to the station—Cuthbert Irwin (Lil's eldest boy) and Eric Sparkes (Sophie's youngest): they are nice chaps—the former top of the school though only thirteen. Yesterday I went to Pontefract with the School Eleven to play for them: but only made 7. E.B.C. came to supper afterwards and was just as usual: I have always liked him in spite of many things to the contrary—you know he was rather fond of you once wasn't he? I have been trying to read some Vergil this afternoon but it wasn't a very great success. I much preferred looking through those wonderful chapters in Shirley, telling of the conflicts between Louis Moore and Shirley: does thou know them? I wrote a brief note to Harry Mennell—though I felt very doubtful whether I ought not to have kept silent, whether he will not resent it as an impertinence from the victor: but it was short and well meant. I have forgotten whether you have most of my songs at Bensham—I shan't be bringing many—there won't be room. Twice a week at the dispensary!—there's another item in thy energetic programme! Ah Mary, see how my knowledge of thee is confirmed over and over again! I hope thou will be up and well again, dearest, tomorrow: I am coming to Bensham at 3 o' clock. I feel as though it would take a while to get used to the serene enjoyment of my treasure, after all these years of conflict. But I will try, sweetheart. Frank.

Ackworth 9.IX .1903 Dearest, How art thou today? None the worse for yesterday, I do trust. This will be crossing one from thee perhaps, but there are a few letters thou will like to see, so I am sending them—some of them are very nice. I think I had better explain who the people are: There is one from my eldest sister Sophie (Mrs Sparkes): also from her eldest boy Malcolm—his reference to the house is because he is in that line—house filling, cabinet making etc of an ornamental type. Then my sister Lucy (Mrs Jackson) and her husband: and then Mrs Theodore Rowntree—and a beautiful letter from Julius. I do feel even now when the far better gift is mine, what a great and good thing is friendship. I was so sorry not to see Bertha in York—I ran across after tea at Mabel's—but she was out—I ought to have sent her a card separately. I wish I could express how I have felt the loving welcome I have had from all thy family. F.A, and Jeanie came down soon after I got home: I hear that Margaret when she was told said 'why wasn't it done five years ago? What's he been waiting all this time for?' —Just the same complain thou made. What a bungler I have been! Ah Sweetheart, I did miss thy loving welcome this morning: I feel as though I had been pretending all these years to know what love was or would be—but now I know I had no conception how sweet it would be. It was hard parting from thee, Mary my darling—and yet there was the sense one had never had before of a triumphant love that could rise above the bonds of space and time—now that our hearts are open to one another—and knit together for ever and ever. And yet how contradictory it seems! For there never was a time, in all the days of longing for thee, when I longed so much as now for thy sweet presence, to hold thy dear hand and look into thy dear brown eyes. It has occurred to me it would be rather nice for thee and me to give Hugh and Mabel a present in memory of a week at Carr End—what does thou think? And what would be likely? I hope Ruth is a little better—tell her not to be a refractory patient. What a long time it will be till Monday! And how shall I take in all the wisdom of the British Association, when my thoughts will be all of more important matters. I didn't read any Virgil on the way home. All my heart's love, Mary dearest, Frank.

The Limes Hydro Southport II.IX.1903 My dearest, It has been very, very lovely to get two letters from thee today! And the messages of thy love, my darling, are very precious. How thou does dive into the future! I think we shall be a loving (though of course sober as we are now!) couple all through life. What amuses me, madam, is that although thou has been swearing all thy life to be an old maid, and art still swearing not to be married for 'ages' , yet thou has evidently carefully considered where to get married, what to wear, how to get the most presents, how many rooms (not to mention beds) to have, how to do without a servant, what kind of socks to make, and what time thy husband ought to retire to rest. Reconcile these things, my dear! Are they all within the last week? But seriously, it will be time enough to consider the date of the wedding when we' ve been engaged a few months (say): why, we' ve only been 'hitched' about ten days, young lady! The idea of laying down the law for a hen pecked husband already! Never mind! I'm not going to express any opinion: only thou may change thy mind! So don't be too dogmatic: thou may get tired of being merely engaged—it will be a time of many partings and much separation. There now, I drop the subject for some time to come: only don't imagine I shall set myself against thy final wishes. It wouldn't be much good if I did: 'man proposes, but woman ------' . There are some lovely letters for thee to see—A.R. and Mrs A.R. and Sturge. Last night Isaac Thompson and Mrs I.T. congratulated me, telling me what a very, very lucky man I was : I know it well, my sweetheart, but it is nice to hear it all the same. I got afternoon tea with JWH. and then walked out with him to the end of the pier—a mile long—getting a fine blow. He and his Mrs send warm congratulations and wishes. I am going to be home about 5 o' clock on Monday, and then I shall soon be able to hold my own precious girl to my heart again. She will always make me happy—and with one loved jewel my home will always be rich— All my love, Mary dearest, Frank. From Mary:Bensham Grove Gateshead-on-Tyne I2.IX.1903 My dearest, I wish I was with thee today. Thank thee so much for thy specially delightful letter. I can't help getting morbid if I lie awake at all, and then when I get thy letter in the morning, everything seems lovely again. Dost thou know I've got a most lovely letter from John Morley this morning. As it came on thy birthday I think it's a sign that I must give thee his book. Ruth says it would be worth while to get engaged just for this letter! She sends thee many messages. Oh, it's so nice to be able to say 'the day after to-morrow.' I've got lots of letters to let thee see, and am longing to see thine. I'm going to York on Monday, arriving there at 11.27, but have not yet found out the trains to Ackworth. I've had rather a tiring day. First of all I went to get a dress tried on. Miss Norman, to whom I have been for years and who is quite a friend of mine was much interested to hear about thee. I made her laugh by telling her thou said I was growing stout, for she said the dress she was altering was at least 2 inches too slack! Then I went servant hunting for Mother, unsuccessfully I'm afraid, and then to Aunt Gertie's, where I began to learn to knit socks. They all came in to watch and teased me fearfully. I got back at 1.0 and after lunch read to Ruth and then at last got down to the Workhouse. The women in the blind ward were very excited and showered blessings upon us, but were a little disappointed that my wanderings had not induced me to bring home an Arab! They were very delighted to hear about thy singing and look forward to hearing thee at Christmas. I told them it was not partiality that made me say thy voice is beautiful, for everyone else said so too. Then I went to see an old Irish woman—Katherine O' Neill—she is 75 and has given me several presents of wonderful knitted work. It took me about 10 minutes to convince her that I was not joking and when I did succeed she was very angry, and said it shouldn't be, etc etc. I couldn't pacify her, even though I said I would take thee to see her—in fact she said she wouldn't see thee—but finally she became rather mollified. She is great fun, and I know she will be delighted when she sees thee. Ruth still may not come downstairs. We had to send for her own doctor, and he says she must be very, very careful. I am sorry for her, for she misses so many things. She is very funny; says she 'nearly fell out of bed in a fit at seeing thee and me sitting on one chair' !! Oh, Frank dear, it will be lovely on Monday 'to have the arms of my true love round me once again' —not, however, 'where he was wont to meet me' . I enclose a few more letters. Please keep them as they are not answered yet, and Father wants to see Mr Graham's. It's stupid of me I forgot to buy a Bradshaw, and our time table doesn't give Ackworth, and they can't tell me the trains at Bensham Station, but I expect there is a train from York arriving in Ackworth sometime in the afternoon, and I can telegraph to 'Jeanie' . I've just been washing my hair, it is so nice to have got it done at last. Aunt Gertie said this morning she had wanted to kiss thee on Tuesday, but was afraid neither of us would like it!! A week ago to-day thou came—I have been thinking of thee specially to-day. It seems a long time ago. The ring has been much admired. I believe I'm getting reconciled to it. Really, though, Frank dearest, I do think it's lovely, and I'm sorry I was so ungracious about it, only I don't like the feeling of 'forms' being a necessity. 'Red, the ruby (in its good sense) signified fire, divine love, the Holy Spirit, heat or the creative power and royalty.' 'White, represented by the diamond or silver, was the emblem of light, religious purity, innocence, virginity, faith, joy and life' . Thy letters were in Ruth's room. I hope thou art having a happy birthday. Goodbye—dearest—ever thine Mariechen. p.s. It is so nice to feel Father and Mother are in the country. They were both worn out, and Sir G.R. said it gave him quite a shock to see Father, he looked so much older and bent than in the spring. My cough has almost entirely gone!