In the course of research for this dissertation, initially every portrait of a Quaker, that was encountered, was noted. As this soon became quite onerous, a restriction was applied, limiting the analysis to portraits that met the following criteria:

Photographic portraits were included if the subject was a Quaker who was born after 1750, or died before 1871, and any of the following were true:

listed in Beck, Wells and Chalkley (1888), Smith (1870) (including the inserted advertisement for the Harvey, Reynolds & Fowler 'Friends' Portrait Gallery carte de visite series, in the Friends House Library copy), or included in the carte de visite albums at Friends House Library

image otherwise known to be before 1871

silhouettes or engraved/painted portraits of the subject also exist

family group

photographic copy of earlier print

Other (Quaker) portraits were included if any of the following were true:

made before 1841 and subject lived into the age of photography

silhouette

miniature

silhouette or miniature exists of subject

subject lived into the age of photography, but no known photo

Portraits noted were entered onto a spreadsheet, which eventually included 1,405 records. The fields (column headings) categorised each image by characteristics of the subject (sex, name, life dates, if included in a group portrait); medium (an initial descriptor field; and logical fields by which photographs, silhouettes, and 'other' media could be readily separated out); photographer or artist (with location of studio, if indicated); location of the image seen (or where reference to it was found, in those cases where the image was known to have existed, but its present whereabouts are unknown); and notes. The 'notes' column was used to record the photographic process, if identifiable; dimensions of the original image, if known; unusual features of the subject (such as the inclusion of five generations of one family, or the subject being obviously working class, or the portrait being clearly the work of an amateur rather than a studio); contextual matter that might assist dating the image; and, where appropriate, an indication that an image was a copy of an earlier image—an engraving after an oil portrait, a daguerreotype copy of a painted miniature, an albumen print copy of a daguerreotype, or whatever.

A number of caveats need to be made, before reporting on the analysis of these records. It is not pretended that the listing was exhaustive or comprehensive in any way. Not only are there doubtless hundreds of Quaker portraits in private hands, quite unknown to the author, but there are probably quite a number overlooked even among the collections examined. One institutional collection—that held by Ackworth School—is known to include approximately 200 portrait photographs of staff and pupils, from before 1870, but there is no listing of this material, and correspondence with the (unpaid) curator of this collection has not succeeded in eliciting any more detailed information; this collection is therefore excluded from the analysis. The catalogues of other collections have a few shortcomings, but at the end of the day the use to which the author was putting them was not one for which they were designed. At Friends' House Library, in addition to working through the picture catalogue, and examining as many individual photographs as was practicable, a protracted trawl was made through all the many memoirs, biographies, collections of letters and so on, relating to the period, that were on the open shelves. However, there are doubtless others that were missed, that are on closed access. (1) Additionally, there are almost certainly portrait photographs in non-biographical materials which were not examined.

A further caveat is that the manner in which portraits were selected for inclusion may well have introduced some bias. By defining criteria for inclusion, and endeavouring to keep within them, bias should be minimal, but the possibility for distortion cannot be ruled out.

Finally, many of the portraits included were available only as half-tone reproductions in printed books, which made it very difficult to be sure, in many cases, of dating or even of the portrait medium. As a guide, of the photographs 36% were only seen as reproductions in books, 32% are original prints held in institutions, 7% are original prints in private hands, 1% were original prints seen tipped into books, and 24% were included in contemporary listings or referred to in publications—so known to have existed—though no print at all was located.

The following analysis, then, must be viewed as suggestive or indicative only.

In all, 837 British Friends had their portraits taken, in the period up to 1870, in media of all descriptions (including photography). Of these 503 were male, 334 female; (a further 91 records were made of family or school groups, or of Quaker gatherings of one sort or another; as they are a complicating factor, they are excluded from further analysis).

Of 324 Friends (187 male, 137 female), only non-photographic portraits are known. Approximately two thirds of these are silhouettes. Only 20 or so are miniatures.

Of 85 Friends only (64 male, 21 female), both photographic and non-photographic portraits are known. Of the non-photographic portraits, there are 30 silhouettes, and 11 miniatures. 70 or so subjects appear to have had (non-miniature) painted portraits made, of which many were also engraved (in some cases engravings are known, but not an original painting). There are three subjects for whom sculpture busts were made: John Bright, John Dalton, and Sarah (Stickney) Ellis.

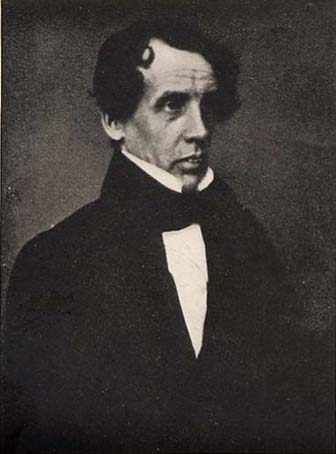

Hannah (Masterman) Stephenson; (courtesy of Friends House Library)

412 Friends (239 males, 173 females) were photographed, of whom no non-photographic portraits are known.

Of these, 56 were photographed by Richard Dykes Alexander. The identity of the photographer is known for only 100 other subjects; in addition to well-known studios such as Elliott & Fry, Maull & Polyblank, and W. & D. Downey, there are exotics like the photograph of Joseph Bevan Braithwaite by Margaritis et Constantin of Athens, or that of Thomas Hanbury taken in Shanghai. A handful of subjects were taken at southern coastal resorts—Brighton, Hastings and Margate; all of these were Quakers for whom no non-photographic portraits are known, perhaps suggesting a slightly lower level of affluence, and more of the air of a special occasion.

Surprisingly few portrait photographs by the known Quaker photographic studios were identified. Those found were: Josiah Forster, Joseph Pease, Christine Alsop, Robert Alsop, Isaac Brown, George Cornish, Josiah Forster, & George Stacey Gibson—all by C.A. Gandy, of London; and William White, by Lambert Weston & Son, of Dover. Richard Noah Bailey, John Henry Douglas and Murray Shipley were all known to have been photographed by S.F. May, of London, but actual prints were not found.

Of photographic processes and print formats, again the caveat must be given that in most cases the original prints have not been seen, so identification is not possible. That said, the Richard Dykes Alexander portraits are salted paper prints, as was perhaps one other seen at Friends' House (that of Samuel Capper), as well as the original of an 1854 photograph only seen in reproduction, of Joseph Lister and six colleagues. At least 43 daguerreotypes were identified, and 12 collodion positives. Unsurprisingly, by far the greatest number (at least 223) were (albumen print) cartes de visite. Just 4 stereographic photographs were identified—those taken at London Yearly Meeting in 1865.

176 British Friends who were born in the 18th century (i.e. before 1800) were identified: 109 men, and 67 women. The Quaker born at the most distant point in history was Mary (Witchell/Bishop) Wright, 1755-1859—the subject of the five-generation photograph already noted.

Most photographs seen were not dated, so in these cases the date of death of the subject had to be used as a surrogate, as a terminus ad quem. On this basis, (and including dated photographs), 24 Quakers are known to have had their photographs taken as early as the 1840s, without counting those included in group photographs known to have been taken at Bootham school in 1848. The earliest known image of an individual brought up as a Quaker in Britain is the daguerreotype of Lewis Weston Dillwyn, taken in September 1841 (see Painting [1987]). The Biographical Catalogue refers to a photograph of William Leatham, who died in 1842; the actual print has not been located and, in any case, it may well have been a photographic copy of a painting or an engraving, rather than an original photographic portrait. Friends' House has an albumen print copy of a photograph of members of the Gurney family, possibly from as early as 1842*. Otherwise the earliest found, dated, photograph of a practising Friend is that of John Ford, Headmaster of Bootham School, taken in 1843 (below).

1. Either at Friends House Library or at the British Library every Quaker diary of the period, that is listed in W. Matthews's bibliography (Matthews 1950), was consulted.

* In 2009 I was notified by Ann Farrant that the original daguerreotype is now held in Special Collections at Haverford College Library. She is confident that this, and another daguerreotype, were taken in Paris on 15 May 1843, by Jean-Gabriel Eynard, the event being recorded in Gurney's journal. [private communication]

© 2001–2023 Benjamin S. Beck

|

|

|

|